25/09/2024

1639 views

36 likes

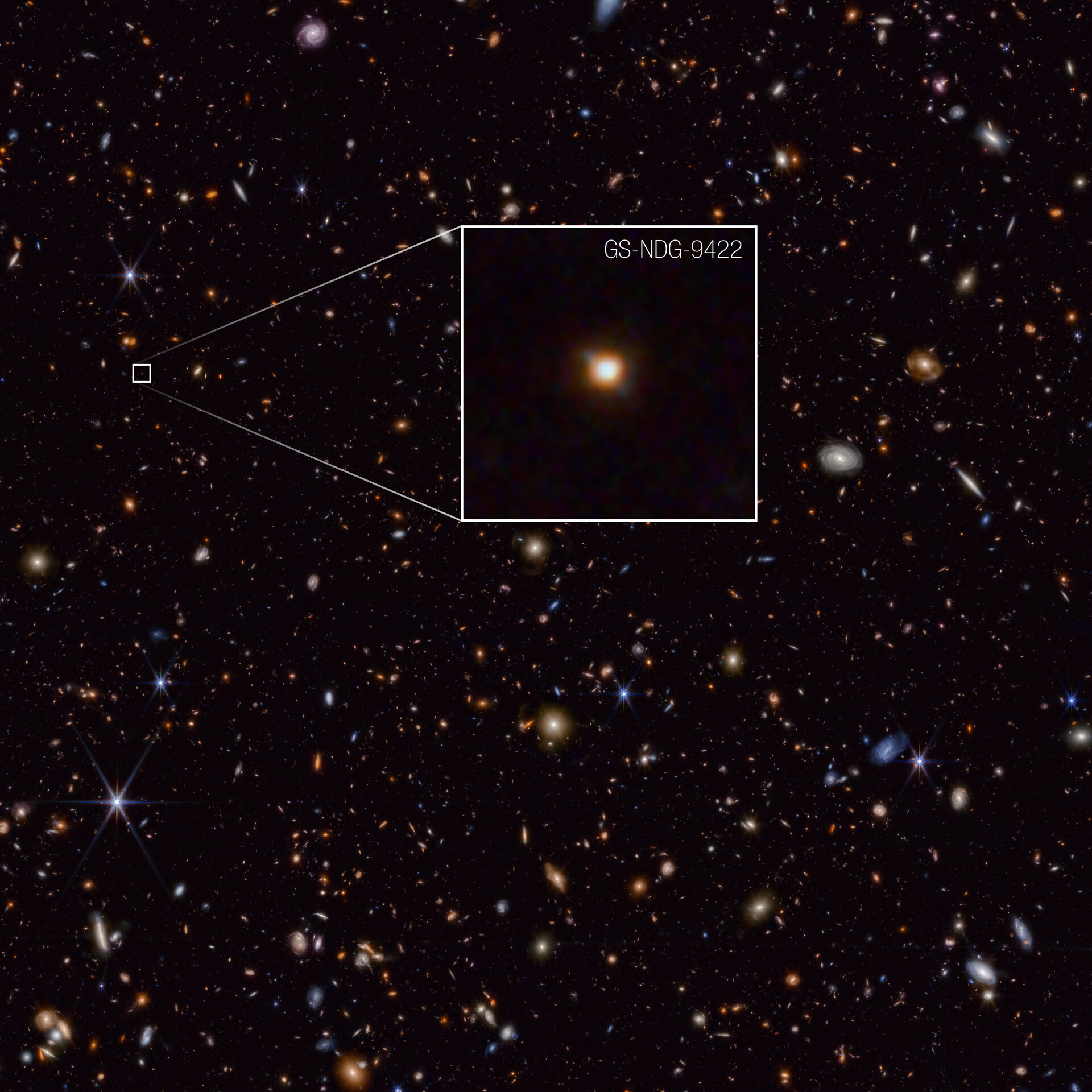

Looking deep into the early Universe with the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers have found something unprecedented: a galaxy with an odd light signature, which they attribute to its gas outshining its stars.

Found approximately one billion years after the Big Bang, galaxy GS-NDG-9422 (9422) may be a missing-link phase of galactic evolution between the Universe’s first stars and familiar, well-established galaxies.

“My first thought in looking at the galaxy’s spectrum was, ‘that’s weird,’ which is exactly what the Webb telescope was designed to reveal: totally new phenomena in the early Universe that will help us understand how the cosmic story began,” said lead researcher Alex Cameron of the University of Oxford, UK.

Cameron reached out to colleague Harley Katz, a theorist, to discuss the strange data. Working together, their team found that computer models of cosmic gas clouds heated by very hot, massive stars – to an extent that the gas shone brighter than the stars – was nearly a perfect match to Webb’s observations.

“It looks like these stars must be much hotter and more massive than what we see in the local Universe, which makes sense because the early Universe was a very different environment,” said Harley, of Oxford, UK, and the University of Chicago, USA.

In the local Universe, typical hot, massive stars have a temperature ranging between 40 000 to 50 000 degrees Celsius. According to the team, galaxy 9422 has stars hotter than 80 000 degrees Celsius.

The research team suspects that the galaxy is in the midst of a brief phase of intense star formation inside a cloud of dense gas that is producing a large number of massive, hot stars. The gas cloud is being hit with so many photons of light from the stars that it is shining extremely brightly.

In addition to its novelty, nebular gas outshining stars is intriguing because it is something predicted in the environments of the Universe’s first generation of stars, which astronomers classify as Population III stars.

“We know that this galaxy does not have Population III stars, because the Webb data shows too much chemical complexity. However, its stars are different from what we are familiar with – the exotic stars in this galaxy could be a guide for understanding how galaxies transitioned from primordial stars to the types of galaxies we already know,” said Harley.

At this point, galaxy 9422 is one example of this phase of galaxy development, so there are still many questions to be answered. Are these conditions common in galaxies at this time period, or a rare occurrence? What more can they tell us about even earlier phases of galaxy evolution? Alex, Harley, and their research colleagues are actively identifying more galaxies to add to this population to better understand what was happening in the Universe within the first billion years after the Big Bang.

“It’s a very exciting time, to be able to use the Webb telescope to explore this time in the Universe that was once inaccessible,” Alex said. “We are just at the beginning of new discoveries and understanding.”

More information

Webb is the largest, most powerful telescope ever launched into space. Under an international collaboration agreement, ESA provided the telescope’s launch service, using the Ariane 5 launch vehicle. Working with partners, ESA was responsible for the development and qualification of Ariane 5 adaptations for the Webb mission and for the procurement of the launch service by Arianespace. ESA also provided the workhorse spectrograph NIRSpec and 50% of the mid-infrared instrument MIRI, which was designed and built by a consortium of nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with JPL and the University of Arizona.

Webb is an international partnership between NASA, ESA and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

The research paper is published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Contact:

ESA Media relations

media@esa.int