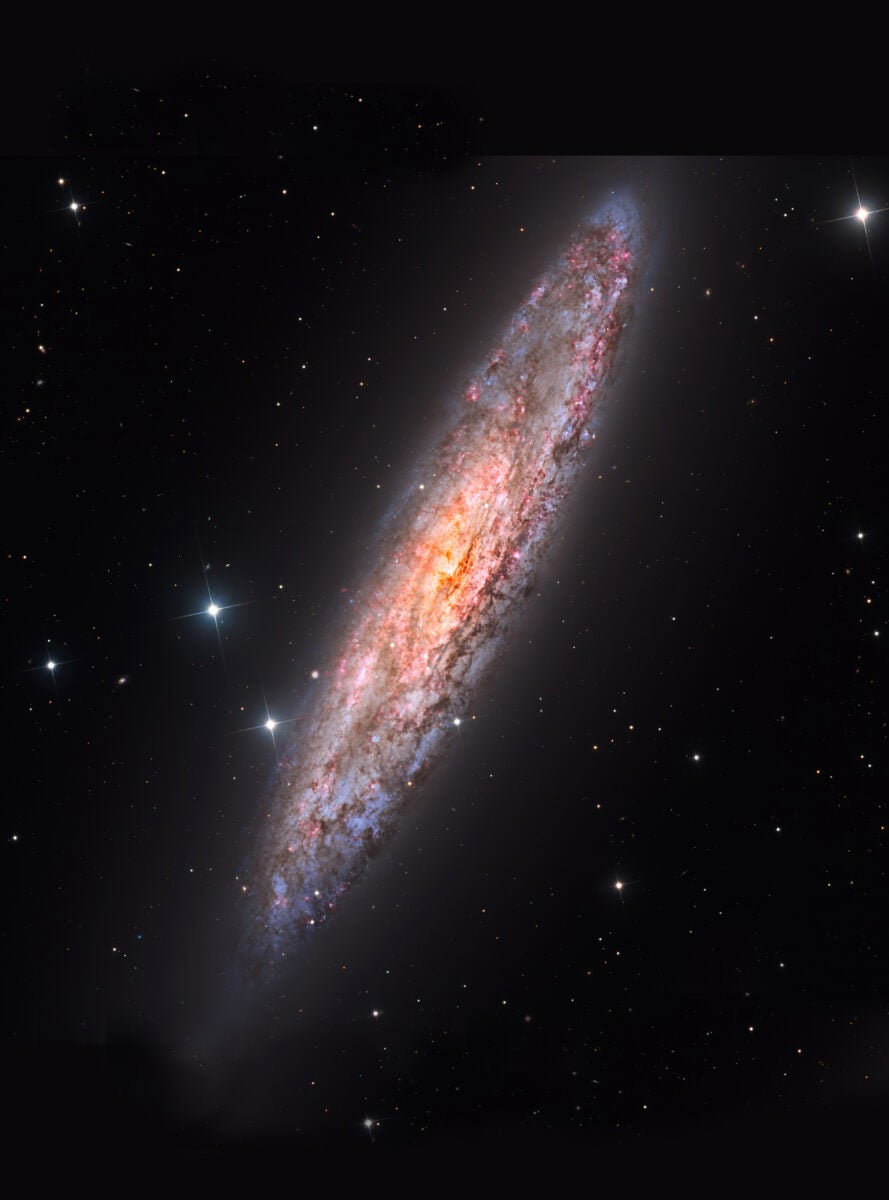

At a distance of 12 million light-years and around 105,000 light-years across, NGC 253’s angular length is close to the diameter of the Full Moon. Credit: Vikas Chander

The constellation Sculptor is not an easy star pattern to find, but it’s worth the effort because it contains some gorgeous deep-sky objects.

Its name comes from French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille, who surveyed the southern sky from 1750 to 1753 at the Cape of Good Hope. He called the pattern “The Sculptor’s Workshop,” but this was later shortened.

Sculptor lies south of the border between Cetus and Aquarius and north of Phoenix. The best time to see this constellation is in the early fall in the Northern Hemisphere, when it reaches its highest point at midnight.

Although Sculptor isn’t huge or bright, the best observers always set aside a few hours each year during its brief window of visibility. It doesn’t contain any Messier objects, but it does boast a handful of nice galaxies and a sweet globular cluster. So, consider packing your telescope and heading south if necessary to place the Workshop and all of the under-observed and overlooked deep-sky objects it holds high in your sky.

Our first object is Bond’s Galaxy, also known as NGC 7793, one of five galaxies with a proper name in this faint constellation. (Sculptor lies at the top of the constellation heap in terms of having common names for objects.) This face-on flocculent — meaning that it has a fluffy or patchy appearance — spiral glows at magnitude 9.0, which lands it on the top 40 chart for brightest galaxies. Indeed, even observers with small telescopes at a dark site won’t have trouble seeing NGC 7793 for two reasons: First, it measures 9.3′ by 6.3′, and second, it has a high surface brightness.

To locate it, aim your scope 5° south-southeast of Delta (δ) Sculptoris, which glows at magnitude 4.6. For those of you using 8-inch or larger instruments, view NGC 7793 through eyepieces that give ever-higher powers until the seeing (steadiness of the sky) breaks down. See if you can trace the closely packed spiral arms by following the gentle curves made by star-forming regions that appear brighter than the gas and dust around them.

Scottish astronomer James Dunlop discovered this galaxy in 1826 from Paramatta, Australia. He found it while using a 9-inch reflector to survey southern sky objects. But the galaxy’s namesake is American astronomer George Phillips Bond, who independently discovered it in 1850 from Cambridge, Massachusetts. At that time, Dunlop’s much earlier discovery was unknown.

Second on our list is the Southern Cigar Galaxy, which also goes by the designations Caldwell 72 and NGC 55. Amateur astronomers gave NGC 55 its common name because it resembles the Cigar Galaxy (M82) in Ursa Major — a lot. At magnitude 7.9, this barred spiral is visible through high-quality binoculars from a dark site. Its large apparent size (32′ by 6′) is due to its distance, a scant 6.5 million light-years away.

To locate this galaxy, point your telescope roughly 4° northwest of 2nd-magnitude Ankaa (Alpha [α] Phoenicis). Then get comfortable, because there’s a lot to see here.

If you start with low magnification, the first thing you’ll notice is that the galaxy isn’t centered on its core; most of the galaxy lies west of it. The overall appearance, then, is that of a celestial cigar. If you then view it at high power, you’ll separate the main part of NGC 55, which contains the most stars, from the other, less starry side.

All along its length, the Southern Cigar Galaxy displays many star-forming regions. One of them even has its own designation, IC 1537. You might be able to spot some of these stellar nurseries if you use an Oxygen-III filter in combination with an 11-inch or larger telescope. (You’ll need that much light-gathering power because the filter won’t let through much light.)

Our third target is the barred spiral galaxy NGC 134. You’ll find it 0.5° east-southeast of 5th-magnitude Eta (η) Sculptoris. It glows at magnitude 10.4 and measures 8.5′ by 1.9′.

Put an eyepiece that gives a magnification of about 100x into an 8-inch telescope and look for an elliptical glow surrounding a starlike nucleus. You won’t see the spiral arms because of their orientation. Through 16-inch and larger telescopes, you’ll just start to see indications of them. They’d be easy to spot if NGC 134 were face on, but they appear tightly wrapped and are thus difficult to separate.

Next, point your telescope at another, slightly smaller, barred spiral galaxy, NGC 150. To locate it, look 5.5° west-northwest of Alpha Sculptoris. It glows at magnitude 11.3 and measures 3.4′ by 1.6′.

Medium-size telescopes won’t show a lot of detail in this galaxy because it’s only half the size of the Milky Way and 70 million light-years away — but you will notice its bright, concentrated core. If you can use an 11-inch telescope, crank the power up as much as the seeing will allow. Then look for a faint ring of light surrounding the brighter core. NGC 150’s spiral arms only show up through 16-inch and larger scopes.

OK, enough of the faint stuff. It’s time to observe one of the top 10 galaxies in the sky, the Silver Coin Galaxy. Also known as Caldwell 65 and NGC 253, this object glows brightly (for a galaxy) at magnitude 7.6, which puts it in easy range of pretty much all binoculars. It’s also huge (again, for a galaxy), measuring 30′ by 6.9′. To find it, look not quite 5° north-northwest of Alpha Sculptoris.

When I was younger (OK, a lot younger), I could see NGC 253 with my naked eyes. You can try it, but it’s an observation that takes a lot of patience. Your latitude matters, too. From 40° north, the galaxy climbs to a maximum altitude of 25°. Even from my current observing location in Tucson, it’s only a bit more than one-third of the way from the horizon to the zenith.

German-born British astronomer Caroline Herschel discovered the Silver Coin Galaxy in 1783 through a 4.2-inch reflecting telescope. It still looks good even through such a small instrument. (Well, better, because telescope optics have come a long way in the past two-and-a-half centuries.) But use an 8-inch or larger telescope, and details really begin to pop.

The first thing you’ll notice is that the galaxy has a slightly spotty look. Observers call this trait mottling. Next, you’ll notice that, unlike the majority of spiral galaxies, the central region doesn’t stand out. Larger scopes and high powers may let you pick out the two main spiral arms. They are not easy to see.

Now we come to the one non-galaxy on our list, globular cluster NGC 288. It glows at magnitude 8.1 and has a diameter of 13.8′.

To find this object, point your scope 3° north-northwest of Alpha Sculptoris. If your site is dark, try viewing NGC 288 and the Silver Coin Galaxy together through binoculars. NGC 288 lies a bit less than 2° southeast of the galaxy.

NGC 288 is unusual because its central region isn’t densely packed, as in most globulars. Because of that, you’ll be able to resolve a couple dozen stars through an 8-inch telescope with a medium-power eyepiece. Higher magnifications in bigger scopes will let you count more than 100 of them.

The next target on our list is a great one: the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, cataloged as Caldwell 70 and NGC 300. This beauty glows at magnitude 8.1 and measures an impressive 20′ by 13′. To find it, look in southeastern Sculptor about 1.7° northwest of magnitude 5.6 Xi (ξ) Sculptoris. It was discovered by Dunlop in 1826 through a 9-inch reflector.

NGC 300 is the ninth-nearest non-dwarf galaxy, lying only 6 million light-years away. Amateur astronomers bestowed on it its common name because it looks a lot like the Pinwheel Galaxy (M33) in Triangulum.

When you observe the Southern Pinwheel, first locate its tiny core. From there, move outward and take note of how wide and bright its central region is. Finally, try to identify the galaxy’s two main spiral arms, which are quite thick.

Next is the Sculptor Dwarf, a dwarf spheroidal galaxy (the first ever discovered), and the most difficult object on this list. To locate it, aim your telescope a bit more than 2° south-southwest of 5th-magnitude Sigma (σ) Sculptoris. Although it glows at magnitude 8.8, don’t be surprised if at first you don’t see it. This galaxy covers an area 1.1° by 0.8°, so it doesn’t just jump out of the background. Observers who have spotted it used low-power eyepieces in large scopes. Once you’re in the area, pan your field of view north and south or east and west until you detect a faint increase in the background glow. That’s it.

Our final target is spiral galaxy NGC 613, a true under-observed gem. It glows at magnitude 10.1 and measures 5.5′ by 4.1′. You’ll find it 0.6° northwest of 6th-magnitude Tau (τ) Sculptoris. A 6-inch telescope will show just a fuzzy oval. Step up to an 11-inch instrument, however, and lots of details will pop into view. Use as high a power as the seeing allows and look for thin spiral arms radiating outward from the bright core.