In addition to creating invaluable maps, Lynds worked to promote education and equality in astronomy for all.

This picture of Lynds in her favorite shirt was taken July 23, 2023. Credit: Rodney Pommier

American astronomer Beverly Turner Lynds died peacefully Oct. 5, 2024 at a hospice in Portland, Oregon, after suffering a stroke in early September. She was 95 years old.

Lynds was born Aug. 19, 1929, in Shreveport, Louisiana, but moved to New Orleans at age three. She attended Centenary College in Shreveport and decided she wanted to become a professional astronomer. She applied to four graduate astronomy programs and was admitted to three, but shortly after she accepted the position at the University of Chicago, the offer was withdrawn when they discovered she was a female graduate student — Beverley (different spelling) is a male name.

She took a position as assistant at Lick Observatory near San Jose, California, where she assisted Nicholas Mayall in measuring the radial velocities of galaxies and George Herbig with spectroscopic programs using the 36-inch refractor. She was subsequently admitted to the graduate astronomy program at University of California, Berkeley and earned a Ph.D. in 1955 with her thesis on the spectra of white dwarves. She married fellow astronomy graduate student C. Roger Lynds in 1954.

In 1960, the Lyndses moved to the new National Radio Observatory in Green Bank, West Virginia, where she assisted the director, Otto Struve, in writing a textbook on astronomy. Struve also charged her with building an astronomy library from scratch, which was a vitally important resource to observatories prior to the internet. She ordered a copy of the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey number 1, which was acquired with that observatory’s 48-inch Schmidt telescope, and immediately noted how well dark nebulae showed up on the plates. She decided she could compile a catalog of dark nebulae that would be superior to that published by E.E. Barnard in 1927.

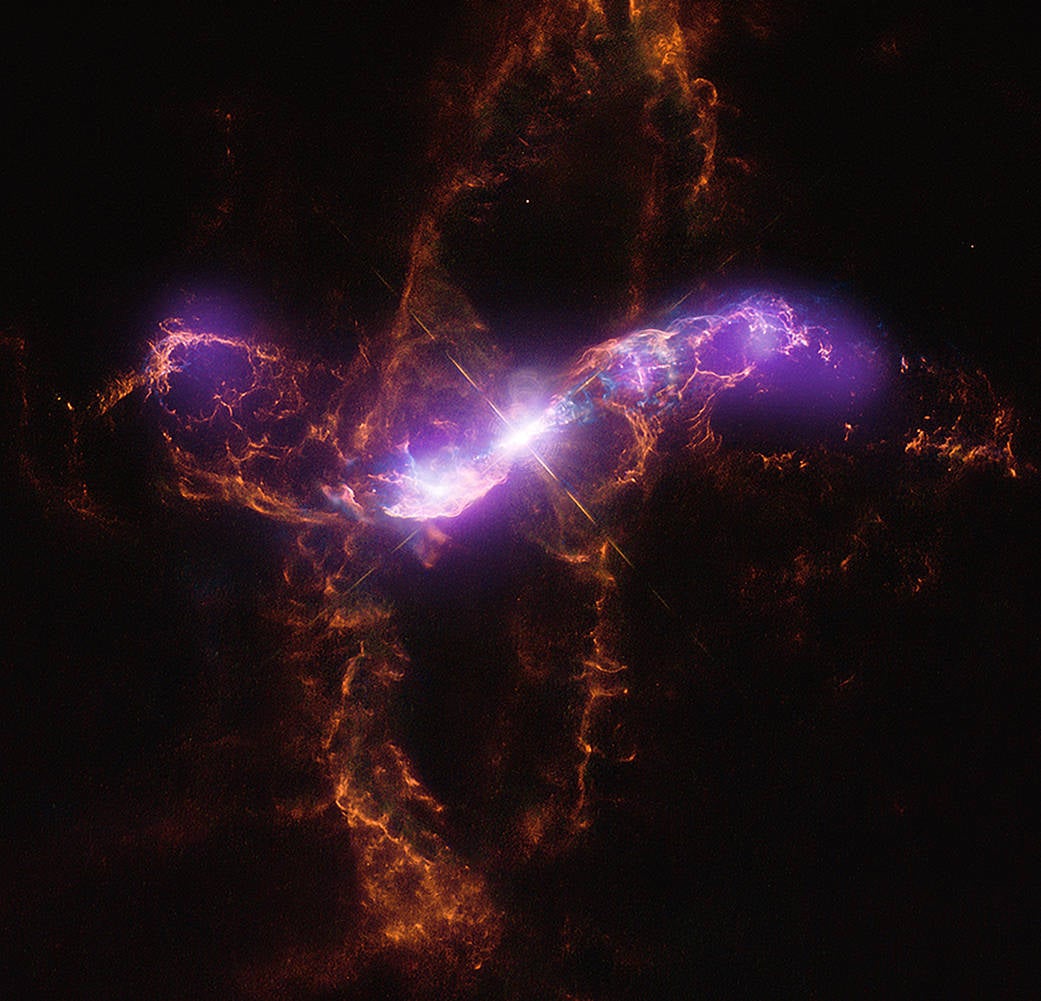

Lynds spent countless hours tracing the outlines of all the dark nebulae she could see on the plates onto tracing paper, recording their coordinates, measuring their areas with a calibrated planimeter, and estimating their darkness on a scale of 1 to 6. She published her catalog of 1802 dark nebulae in the Astrophysical Journal in 1962. It is now regarded as a landmark catalog on par with the Messier, New General, Index, and Sharpless catalogs, and currently has nearly 1,000 citations in the scientific literature. She subsequently repeated this process with known and unknown emission and reflection nebulae — but not planetary nebulae — and supernova remnants, publishing her catalog of bright nebulae in the Astrophysical Journal in 1965.

Lynds went on to study the relationship between bright and dark nebulae, finding this easier to analyze in other galaxies than from our limited view within a spiral arm of our Milky Way Galaxy. Alan Sandage lent her Hubble’s collection of glass plate exposures of galaxies for her work. Astronomer C.C. Lin found her work supportive of his density wave theory for the formation of spiral arms in galaxies. She subsequently did the first study of dust in M20, the Trifid Nebula, using the new technology of CCD imaging. She also served as Assistant Director of Kitt Peak National Observatory in Tucson, Arizona.

After retirement, she devoted much of her time to science education and reducing racial and gender disparities. She served as a Shapley Visiting Lecturer for the American Astronomical Association, specifying she only wanted to visit minority colleges. She received the 1999 Education and Outreach award from the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research.

Lynds is survived by her daughter, Susan (Scott) Lynds.