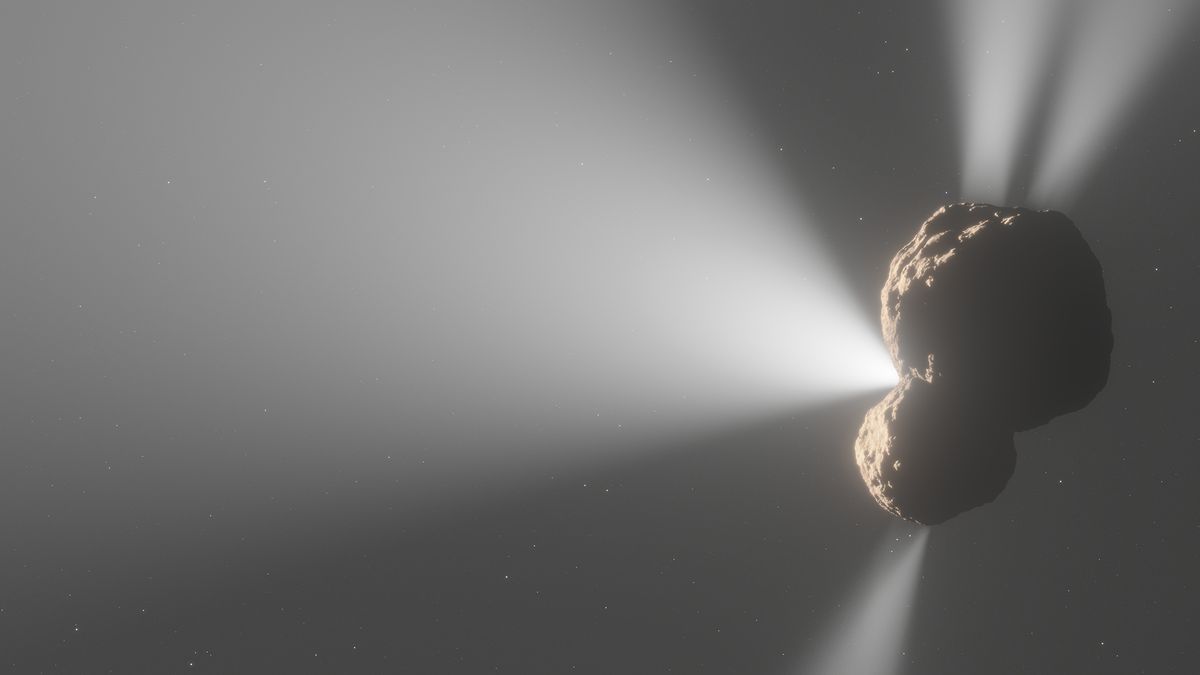

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists have witnessed jets of primordial gas from the birth of the solar system spewing from a distant, comet-like object called a centaur.

The observations provide clues as to how this centaur and others formed, what they are made of, and how they eventually transition into full-fledged comets, the research team said in a study published in the journal Nature.

Centaurs once resided in the frozen Kuiper Belt beyond the orbit of Neptune. However, the gravitational interplay with Neptune, or even occasionally with a close encounter with a star, acts to nudge some of them farther inward, where they orbit the sun between Jupiter and Neptune. There, the centaurs come under the influence of Jupiter’s orbit, which can drag some of them even closer to the sun, turning them into short-period comets that orbit our star in less than 200 years.

Over 500 centaurs have been discovered, but astronomers estimate that there could be as many as 10 million out there.

“Centaurs can be considered as some of the leftovers of our planetary system’s formation,” Sara Faggi, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who led the research, said in a statement. “Because they are stored at very cold temperatures, they preserve information about volatiles [gases with low boiling points, such as water] in the very early stages of the solar system.”

Related: What cosmic object ‘Arrokoth’ can tell us about our solar system’s formation

One of the most prominent centaurs is 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1, which undergoes outbursts every six to eight weeks. Previous radio wavelength observations had shown a jet of carbon monoxide gas pointed roughly at the sun, but JWST’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) showed much, much more.

NIRSpec revealed a second carbon monoxide (CO) jet emanating from 29P and pointing northward (with respect to the plane of the solar system). It also discovered two never-before-seen jets of carbon dioxide (CO2), pointing north and south.

What is prompting the outgassing is uncertain. On regular comets, gaseous jets form when water ice warms in the sun’s heat, vaporizing and bursting through the surface to form the comet’s tail and carrying these gases with it. Yet JWST found no evidence for water vapor in the jets. This was unsurprising to the researchers, because 29P is too far from the sun for water ice to sublimate. Instead, it remains frozen. So what’s causing the outgassing?

Faggi’s team cannot answer that yet, but the details of the jets hint at the remarkable conclusion that 29P is not one object but rather several objects that have become stuck together. Such objects are called “contact binaries,” and astronomers are finding more and more of them. For example, Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, which was visited by the European Space Agency‘s Rosetta mission, was a contact binary, as was Arrokoth, the distant Kuiper Belt object encountered by the New Horizons spacecraft on New Year’s Day 2019.

Centaur 29P is too distant for even JWST to resolve its nucleus. But 3D computer modeling of the points of origin of the outgassing jets suggests they are in different locations and that different parts of 29P are made from different materials.

“The fact that centaur 29P has such dramatic differences in the abundance of CO and CO2 across its surface suggests that 29P may be made of several pieces,” Geronimo Villanueva, associate director of the Solar System Exploration Division at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and a member of the research team, said in the statement. “Maybe two pieces coalesced together and made this centaur, which is a mixture between very different bodies that underwent separate formation pathways. It challenges our ideas about how primordial objects are created and stored in the Kuiper Belt.”

Asteroids, comets, Kuiper Belt objects and centaurs are all relics of the formation of the solar system, and most of them have gone untouched for 4.5 billion years. Therefore, any materials we see outgassing from them are from the era of our solar system’s birth and could contribute to our understanding of how the solar system formed.

The next step is to look back at 29P with JWST for longer, to watch if the jets change direction — perhaps if 29P rotates, the jets switch off or new jets switch on.