GOLDEN, Colorado — NASA is faced with the challenge of safely deorbiting, in one fell swoop, over 400 tons of space hardware in a few years. As of now, the agency plans on deorbiting the International Space Station in early 2031 by dragging it back toward Earth and dumping it into an isolated patch of the Pacific Ocean — an idea that has scientists and environmental watchdogs ringing alarm bells.

As recently reported by the NASA Office of Inspector General (OIG), the orbital outpost is plagued by ongoing wear-and-tear issues, such as cracks and air leaks, after decades of use.

NASA has examined and rejected several options for decommissioning the ISS, including disassembly and return to Earth, storing the facility in a higher orbit and even a natural orbital decay scenario with uncontrolled reentry. Instead, NASA concluded in a white paper that “using a U.S.-developed deorbit vehicle, with a final target in a remote part of the ocean, is the best option for station’s end of life.”

Destructive nosedive

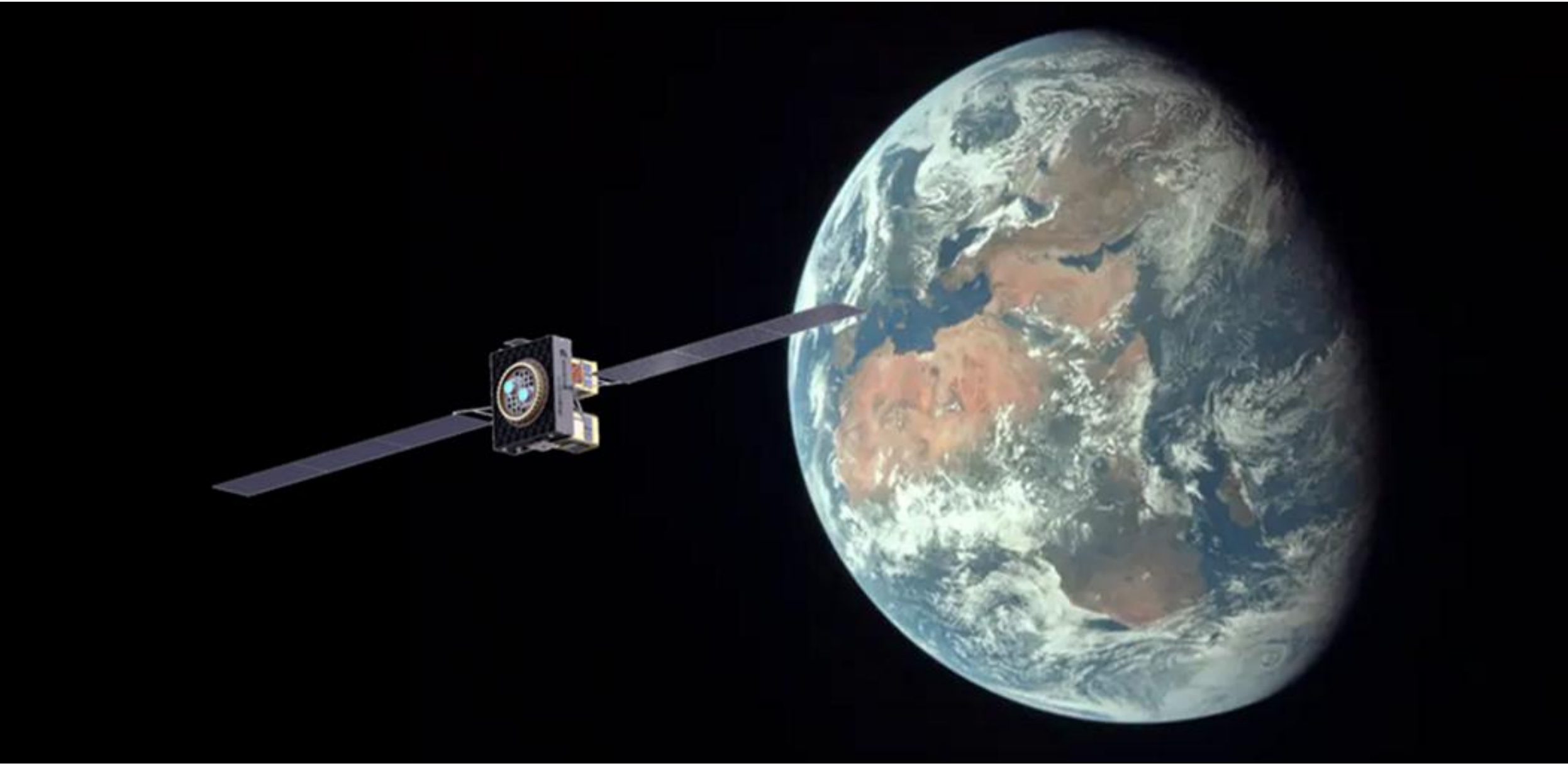

NASA announced last June the selection of SpaceX to design the United States Deorbit Vehicle (USDV) under a contract worth up to $843 million. The USDV will be based on a redesigned Dragon spacecraft outfitted with more Draco thrusters to lower the station’s orbit for a powered, destructive nose-dive. An enhanced trunk section for the USDV includes engines, propellant tanks with six times more propellant than a typical Dragon spacecraft, power generation and other systems.

Most ISS components are expected to “burn up” during re-entry. But some denser or heat-resistant components are expected to survive re-entry.

The likely drop zone for these hardier components is Point Nemo, formally dubbed “the pole of inaccessibility,” which is already in use as a watery cemetery for decommissioned space hardware due to its status as the farthest point from dry land on Earth. The site is about 1,450 nautical miles (2,685 kilometers) from the nearest piece of dry land. The closest landscape is Ducie Island, part of the Pitcairn Islands, to the north; Motu Nui, one of the Easter Islands, to the northeast; and Maher Island, part of Antarctica, to the south.

Wave of worry

The ISS splashdown, however, is stirring up a wave of worry among several environmental watchdog groups and marine environment specialists.

“I consider this idea very questionable,” said Edmund Maser, a molecular biologist at the Institute of Toxicology and Pharmacology for Natural Scientists at the University Medical School Schleswig-Holstein in Kiel, Germany.

Maser said that ocean dumping has historically been a short-sighted solution that’s comparable, he explained, to 80 years ago when it was considered a good idea to dump unused ammunition from World War II in the oceans. “Today, it turns out that the ammunition is corroding and spreads its explosives into the marine environment,” he told SpaceNews.

It was later determined that these explosives can not only explode, thus posing an acute danger to people and the environment, Maser said, but that they are also toxic and carcinogenic. Decades ago, he added, no one thought of these chronic negative effects on the marine environment and people, and now today people are faced with the difficult and expensive task of cleaning up the old ammunition.

“It is therefore foreseeable that we will cause great damage with the planned dumping of ISS and others,” Maser said. “Our future generations will hold us responsible for this and will criticize us, shaking their heads — and they will have to make a huge effort to correct our current mistakes.”

Surviving debris

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is evaluating how the disposal of the International Space Station into the ocean will need to be regulated but has not shared the details of any specific concerns or aspects of regulation.

“EPA’s Office of Water is coordinating with the Office of General Counsel on this complex issue. The agency does not have a timeline for this evaluation,” EPA spokeswoman Dominique Joseph told SpaceNews.

“Sixty-six years of space activities has resulted in tens of thousands of tons of space debris crashing into the oceans,” said Ewan Wright, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of British Columbia and a junior fellow of the Outer Space Institute, an interdisciplinary group of experts working on emerging space sustainability issues.

Wright noted that there are several unknowns about the ISS deorbiting process, which will be the largest reentry in history.

“We don’t know exactly what materials are on the ISS, and the surviving debris may be a hazard to marine life,” Wright said. “But dumping it into the ocean is the least worst option, minimizing the risk to people and aircraft, and stopping it from being hit by space debris in orbit.”

While deorbiting the ISS may clear space in orbit for other spacecraft, dumping it in the ocean is a shortsighted answer, George Leonard, chief scientist of the Ocean Conservancy — a Washington, D.C.-based group dedicated to protecting the ocean from today’s greatest global challenges — told SpaceNews.

Leonard compared NASA’s plan to dumping single-use plastics in the ocean: it renders the pollution out of sight and out of mind.

“For many, this has meant that the ocean has been a convenient dumping ground for everything from tires to old ships to barrels of radioactive waste, and of course, space junk,” Leonard said. “The debate over the disposal of the International Space Station underlies the fact that humans often fail to plan for the end-of-life of the stuff we produce,” he said, “and the ISS and a plastic fork aren’t so different.”

Leonard said that the ocean suffers every time we put pollution into it.

“Space debris being left in our ocean is nothing new, but it’s a problem that we know will only grow in the future. There’s no easy solution, but we cannot ignore the long-term consequences that inevitably come from adding waste — whether it be single-use plastics or space junk — into our ocean,” Leonard said.