The sun has been rather quiet of late but has since roared back to life with a major X-class solar flare eruption, the most powerful class of solar flare.

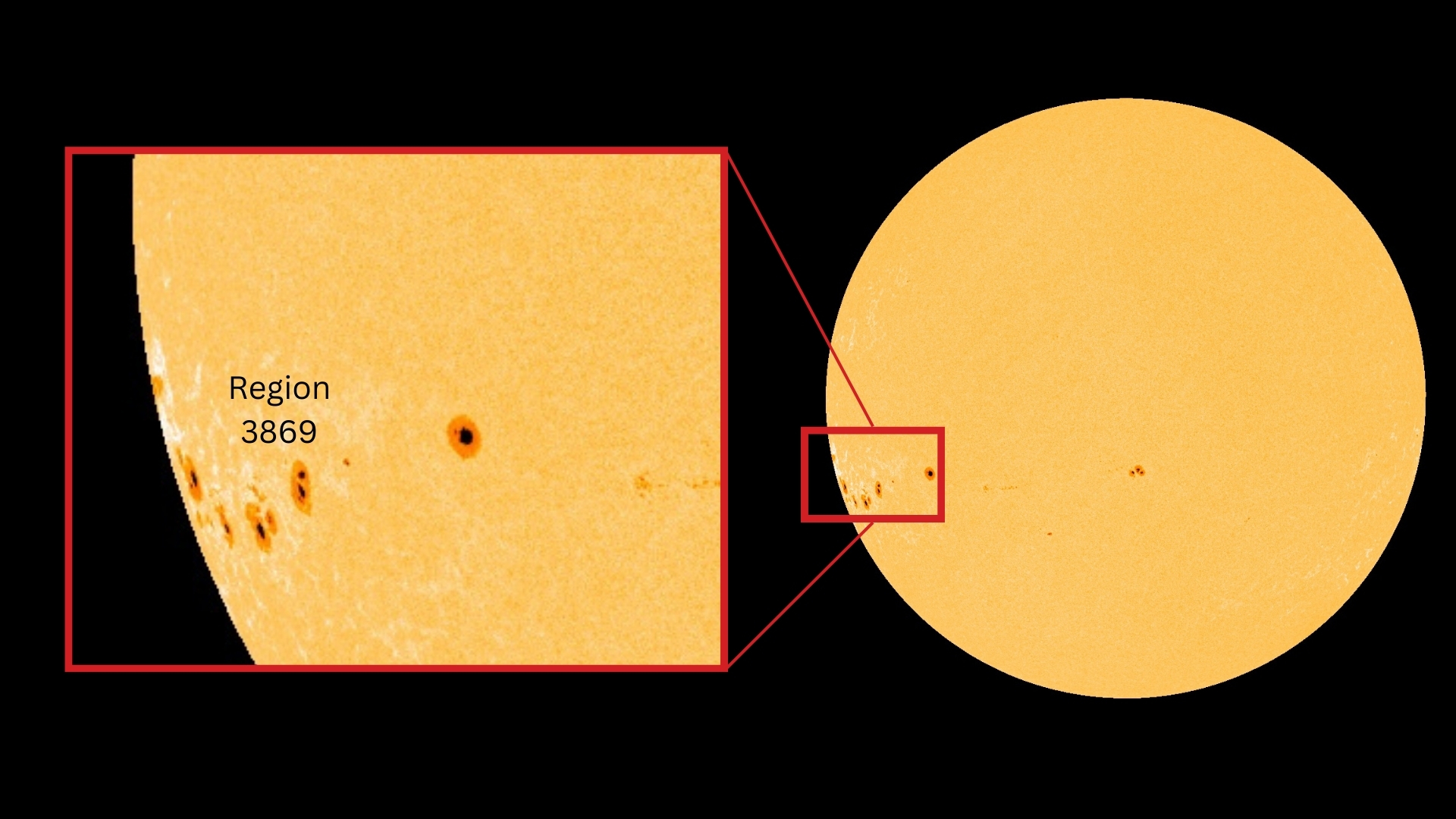

The intense solar flare originated from sunspot region AR3869 and unfolded over the span of an hour, reaching its peak at 11:57 p.m. EDT on Oct. 23 (0357 GMT on Oct. 24). Extreme ultraviolet radiation from the eruption triggered shortwave radio blackouts over Australia and Southeast Asia.

The eruption was accompanied by a coronal mass ejection (CME) — a plume of plasma and magnetic field, according to space weather forecaster Sara Housseal’s post on X. “As expected with the return of many regions, big solar flare activity has also returned. AR3869 wasted no time with going straight for an X3.3 flare earlier today with a large CME,” Housseal wrote. “These regions will need to be watched over the coming days as they rotate westward and face Earth.”

When CMEs hit Earth they can trigger geomagnetic storms like the ones experienced earlier this month that lead to impressive northern lights stretching into mid-latitudes. But before you aurora hunters start getting too excited, note that it is unlikely any significant portion of a CME released during the event will impact Earth due to the position of the sunspot at the time of eruption . But, as we are still awaiting CME models, we cannot say for certain that Earth won’t at least receive a glancing blow. Watch this space!

Space weather forecasters and aurora chasers alike will be keeping a watchful eye on AR3869 as it crackles with solar activity. Over the next few days, the sunspot region will rotate into the “Earth strike zone” whereby any CME released during this time is more likely to hit Earth. AR3869 is not alone. Several large sunspots are also rotating into view over the sun‘s southeastern limb, so we could be in for even more solar action in the coming days.

What are solar flares?

Solar flares are explosive events on the sun’s surface that emit strong bursts of electromagnetic radiation. These flares occur when magnetic energy accumulates in the solar atmosphere and is rapidly released. They are categorized by intensity, with X-class flares being the strongest. M-class flares are 10 times less intense than X-class, followed by C-class, which are 10 times weaker than M-class. B-class flares are 10 times weaker than C-class, while A-class flares, 10 times weaker than B-class, typically have no noticeable effects on Earth. Each class also has a numerical scale (1 to 10 and beyond for X-class) to further indicate flare strength.

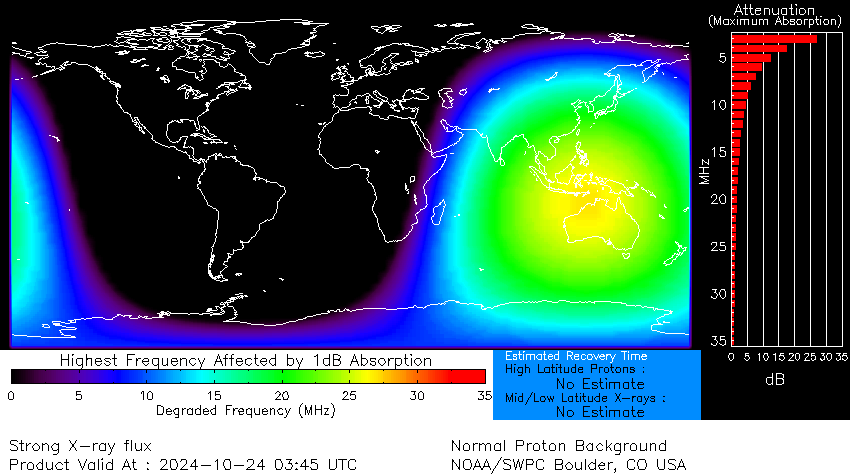

Shortwave radio blackouts

Shortly after the X-class solar flare erupted shortwave radio blackouts were detected over Australia and the Southeast Pacific, the sunlit portion of Earth at the time of the eruption. These shortwave radio blackouts are not uncommon during such explosive events and result from the intense burst of X-rays and extreme ultraviolet radiation emitted during the X-flare.

Radiation from solar flares travels to Earth at the speed of light, ionizing the upper atmosphere when it arrives. This ionization increases the density of the atmosphere, affecting high-frequency shortwave radio signals used for long-distance communication. As these radio waves pass through the electrically charged, ionized layers, they experience energy loss due to more frequent collisions with electrons, which can weaken or even fully absorb the radio signals.

Editor’s note: If you capture a stunning photo or video of the northern lights (or southern lights!) and want to share them with Space.com for a possible story, send images, comments on the view and your location, as well as use permissions to spacephotos@space.com.