Now Reading: The moon doesn’t have a magnetic field, so why does it have magnetic rocks?

-

01

The moon doesn’t have a magnetic field, so why does it have magnetic rocks?

The moon doesn’t have a magnetic field, so why does it have magnetic rocks?

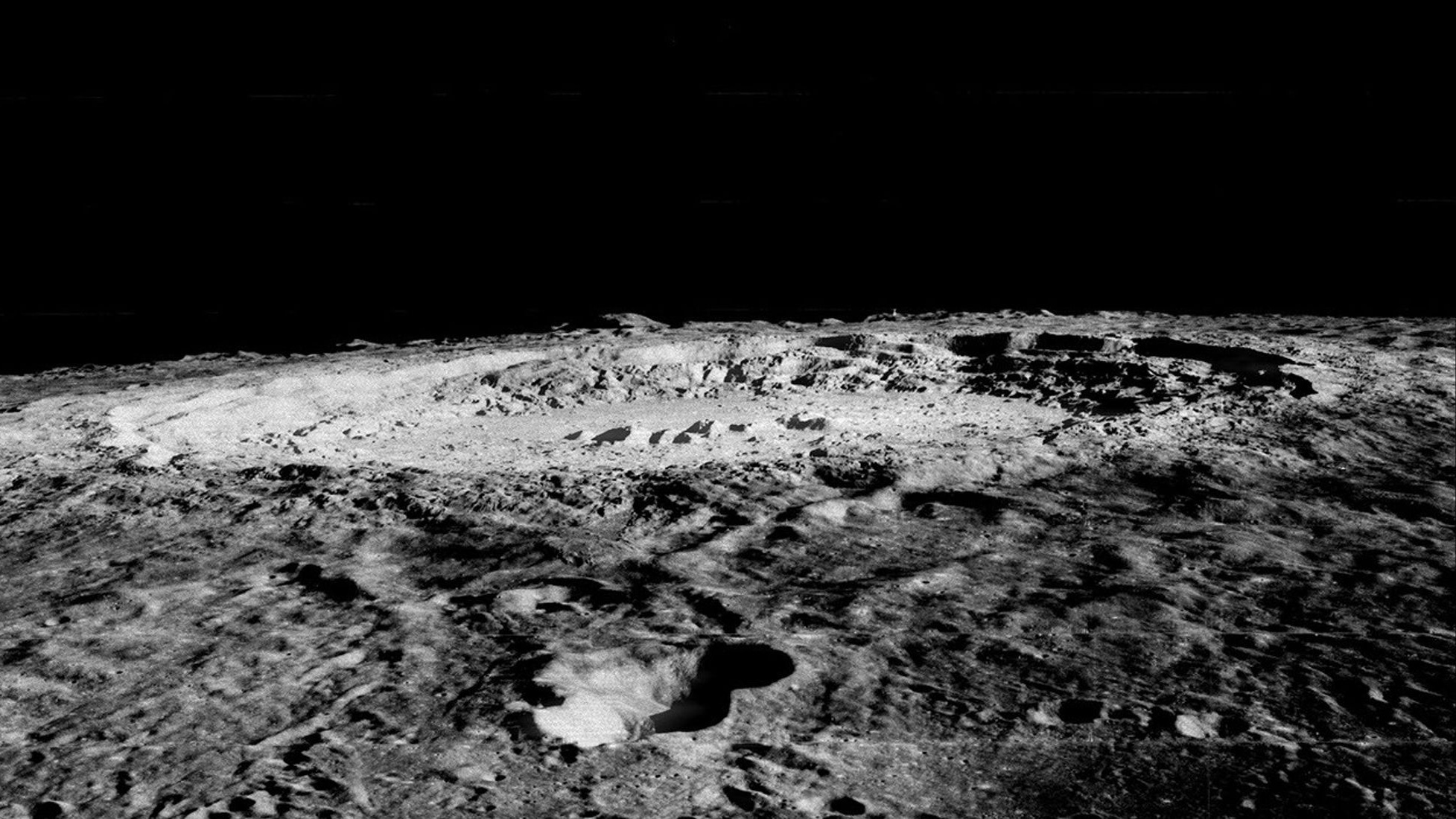

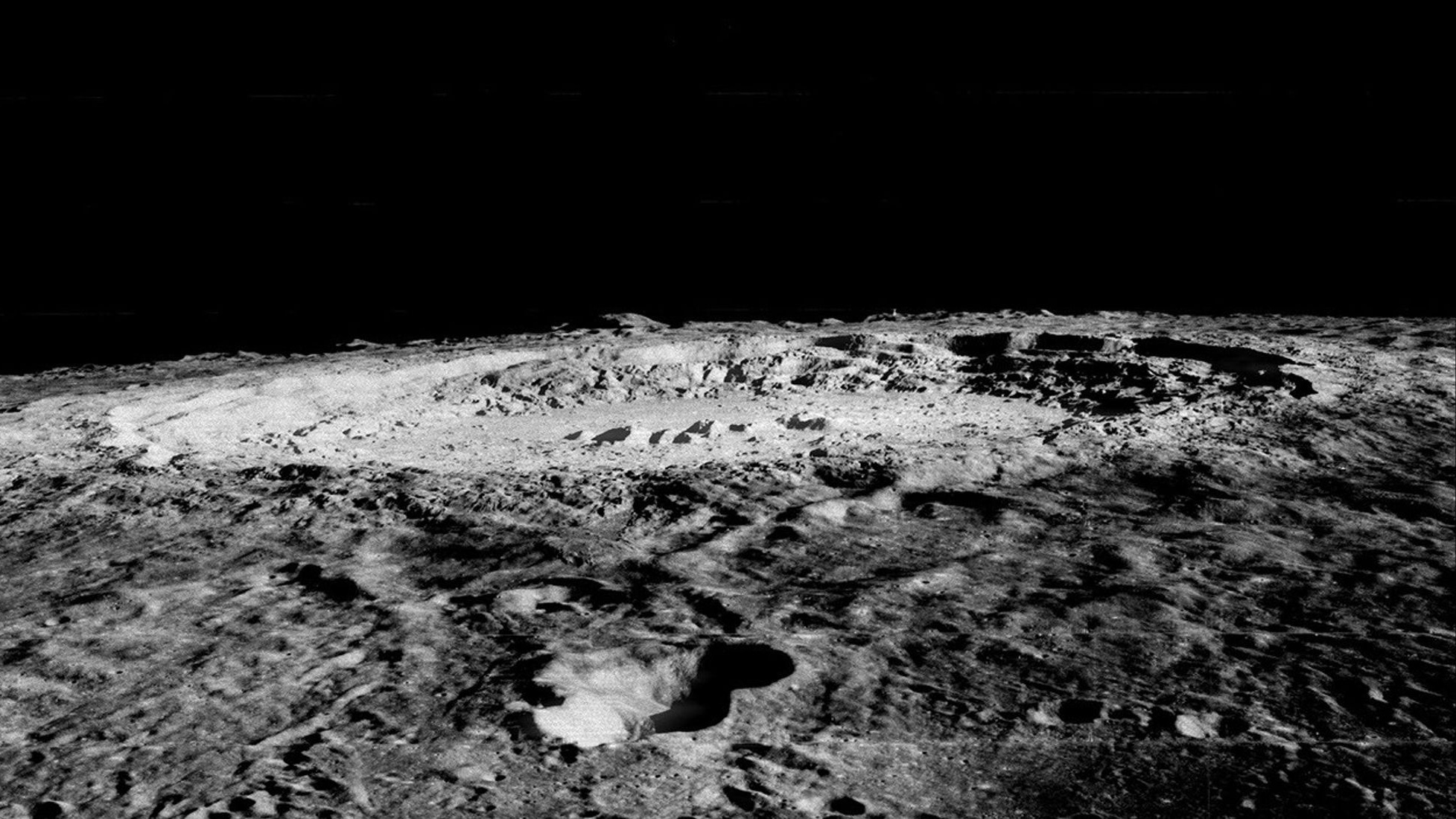

For decades, scientists have been trying to understand why some rocks on the moon are strongly magnetized even though the moon has no magnetic field today.

Moon rocks brought to Earth during NASA’s Apollo missions in the 1960s and ’70s, as well as data from orbiting spacecraft, have shown that parts of the lunar surface — particularly on the farside — contain rocks with surprisingly strong magnetic signatures. New computer simulations suggest a massive asteroid impact billions of years ago may have briefly amplified the moon‘s old, weak magnetic field, leaving behind a magnetic imprint still detectable in lunar rocks.

“The majority of the strong magnetic fields that are measured by orbiting spacecraft can be explained by this process, especially on the far side of the moon,” Isaac Narrett, a graduate student in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, who led the new study, said in a statement.

While the moon once had a weak magnetic field generated by a small molten core, the team’s research suggests it likely wouldn’t have been strong enough on its own to magnetize surface rocks. However, a massive asteroid impact may have changed that — at least briefly.

Simulations by Narrett and his team show that a powerful impact, quite possibly the one that created the moon’s massive Imbrium basin, would have vaporized surface material and created a cloud of superheated, electrically charged particles known as plasma. As the plasma enveloped the moon, much of it would have concentrated on the opposite side of the impact, temporarily amplifying the moon’s magnetic field in that region. Rocks in the area could have captured this short-lived magnetic surge before the field faded away, according to the new study.

The findings suggest the impact would have triggered seismic shockwaves that swept through the moon and converged on the far side. These waves likely “jittered” the electrons in nearby rocks just as the magnetic field peaked — effectively locking in the field’s orientation like a geological snapshot.

The researchers estimate the entire sequence would have played out in less than an hour, but likely left behind a magnetic signature that’s still detectable today.

Related Stories:

“It’s as if you throw a 52-card deck in the air, in a magnetic field, and each card has a compass needle,” study co-author Benjamin Weiss, who is a professor of Earth and planetary sciences at MIT, said in the statement. “When the cards settle back to the ground, they do so in a new orientation — that’s essentially the magnetization process.”

Future missions could put the team’s theory to the test. The most strongly magnetized rocks lie near the moon’s south pole, on the farside — an area that several international missions, including NASA’s Artemis program, plan to explore in the coming years. If those rocks show signs of both shock and ancient magnetism, it could confirm that the moon’s magnetic anomalies were due to a colossal asteroid impact.

“There are large parts of lunar magnetism that are still unexplained,” said Narrett.

The study was published on Friday (May 23) in the journal Science Advances

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly