Now Reading: NASA’s budget crisis presents an opportunity for change

-

01

NASA’s budget crisis presents an opportunity for change

NASA’s budget crisis presents an opportunity for change

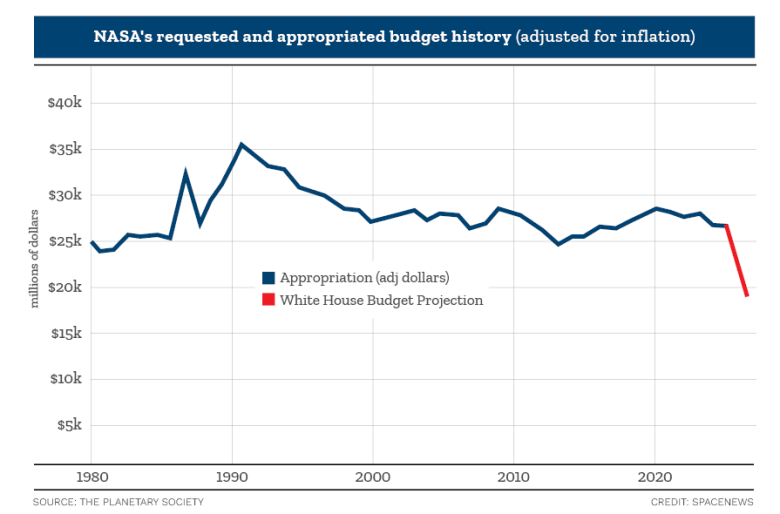

When the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) released its top-level budget proposal for fiscal year 2026 on May 2, NASA and the space industry feared the worst. Leaks of an OMB “passback” budget document to NASA in April revealed the White House was proposing a nearly 50% cut to NASA science, including canceling many missions in development. Was that an outlier or a harbinger of cuts elsewhere at NASA?

It appeared the latter. That so-called “skinny” budget proposal — so named because it lacks the details of the full budget, yet to be released — sought an overall $6 billion cut for NASA, a reduction of nearly 25% from its 2025 budget. While there would be some increases in exploration, the budget proposed major cuts to science, space technology and space operations.

“A 25% budget cut is the most significant NASA has seen ever,” said Alex MacDonald, a former NASA chief economist who is now a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). When adjusted for inflation, he noted, the overall budget “is equivalent to the budget request from 1961 or 1962.”

Cuts of such magnitude, if accepted by Congress, would likely require not just cancelling missions and programs. Many believe they also require a restructuring of the agency itself. It could result in thousands of jobs lost, put longstanding international partnerships at risk and leave NASA entirely dependent on commercial providers for human spaceflight by the end of the decade.

But others said that those changes, while painful, may be what NASA needs.

NASA’s muted reaction

Since the release of the skinny budget, NASA officials have offered few details about the implications of the cuts on their programs, saying they know little beyond the outline that document provided. [Editor’s note: More details about NASA’s budget have come to light since our June 2025 issue, which included this article, went to the printers. You can read our updated coverage of the proposed 2026 NASA budget here.]

At a May 15 hearing of the House Science Committee’s space subcommittee on NASA’s planetary defense efforts, Democratic members asked Nicky Fox, NASA’s associate administrator for science, about the nearly 50% cut in science proposed in the budget. Fox said she couldn’t discuss what missions might be canceled or curtailed based on the limited information in the skinny budget.

“We have not seen any details on the missions or any direction on the missions other than the Mars Sample Return program and Landsat Next,” Fox said. Those two were the only missions mentioned by name in the skinny budget — to be canceled and restructured, respectively. “We await the full president’s budget so we can see the priorities and direction on which missions may be supported or not supported.”

That lack of details raised questions about one of the missions highlighted at the hearing: NEO Surveyor, a $1.2 billion infrared space telescope designed to search for near Earth asteroids. Amy Mainzer, a professor at the University of California Los Angeles who leads the mission, said at the hearing she has received no guidance yet on any changes to NEO Surveyor, set to launch in the fall of 2027. “From my perspective, we do not know the impact yet.”

The skinny budget also proposed a cut of about 50% in NASA’s space technology account, but said little about how the cuts would be distributed beyond canceling “failing space propulsion projects.”

Clayton Turner, NASA associate administrator for space technology, said at the spring meeting of the Lunar Surface Innovation Consortium May 20 that a steep cut in his budget would require reprioritizing technology investments.

“If it goes down a lot,” he said of the spending, “then we have to, as a community, find what are those priorities.” That could include, he suggested, work on “survive the night” technologies to enable lunar landers to make it through the two-week lunar night as well as other technologies for exploration, tied to the budget’s focus on human missions to Mars.

“We will set priorities, we will set direction to get to that long-term goal,” he said. “That may not be a nice, clean answer … but we are going to navigate that, and we’ll do that together.”

The skinny budget included a $500 million cut in the budget for the International Space Station, calling for reductions in the crew size on the station and research there. It also continued work to retire the station by the end of the decade. While the proposal was the first public mention of reducing the size of the crew, NASA said it had already been studying that possibility.

“The station has been faced with a cumulative multi-year budget reduction,” said Dana Weigel, NASA ISS program manager, at a May 20 briefing about an Axiom Space private astronaut mission to the station. “That has left us with some budget and resource challenges that result in less cargo.”

She said even before the release of the skinny budget, NASA had been looking at reducing the size of the crew on the U.S. segment of the station from four astronauts to three. “That’s something that we’re working through and trying to assess today,” she said, noting no decision had been made yet.

Because of that work, Weigel said she had not sought details about the proposed cut. “When we see the full president’s budget request, we’ll take a look at those details to really understand what changes or adjustments will need to be made,” she said.

Human spaceflight implications

In some respects, the skinny budget was also less radical than expected. In the early days of the second Trump administration, there was widespread speculation among the space community that it would seek to immediately cancel much of Artemis, including the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft. Instead, the budget keeps SLS and Orion going through Artemis 3.

“When we thought about this maybe two months ago, many of us thought we would see more Mars and less moon” in the budget, said Mike French, founder of the Space Policy Group and a former NASA chief of staff.

Speaking at a CSIS event May 14, he credited members of Congress for pushing back against more radical changes. That included Jared Isaacman’s Senate confirmation hearing in April when members of the Senate Commerce Committee got Isaacman to endorse lunar exploration and at least near-term continued use of SLS and Orion.

“We saw quite a bit of policy development around the framework of human exploration happen in a very accelerated timeframe,” he said. “The skinny budget is putting forward what looks like a policy debate that happened already.”

However, those near-term compromises belie more fundamental longer-term changes to the agency. “Under this budget proposal, NASA would not have any operational vehicles in space within about five years for humans,” MacDonald noted at the same event. That accounts for the phasing out of SLS and Orion, cancellation of Gateway and retirement of the ISS.

Barring the introduction of new elements, such as a lunar habitat or Mars spacecraft, NASA will rely exclusively on service providers for human spaceflight capabilities, an extension of a trend that started with ISS cargo and crew transportation.

“It’s such a huge shift I’m not quite sure we’re even ready to talk about the potential implications of that,” he said.

For example, relying entirely on commercial spacecraft could alter public perceptions of NASA. “If you don’t have any publicly owned vehicles that NASA is operating,” he suggested, “you might see a reduction in overall support.”

The proposal to cancel the Gateway was not unexpected, but brings with it questions about the roles international partners will play in NASA’s human spaceflight. Most of the Gateway components are coming from Canada, Europe, Japan and the United Arab Emirates.

“It’s one of the critical elements of international partnership,” MacDonald said. If Gateway is canceled, “one immediate question is how are the international partners going to be part of Artemis?”

One possibility is that NASA works with the Gateway partners to either repurpose their components or otherwise renegotiate their agreements to instead support activities on the lunar surface.

“We’ve seen this administration first upset the apple cart and then rapidly seek to ink new deals,” said Peter Garretson, senior fellow in defense studies at the American Foreign Policy Council. He was speaking during a panel discussion hosted by the Coalition for Deep Space Exploration May 16.

He added a potential shift to lunar surface contributions might be welcomed by the countries participating on Gateway. “Ultimately, they may be much more excited about making history on the lunar surface than watching it from above.”

Job reductions

Another potentially overlooked change involves cuts in “mission support,” part of a budget line formally called Safety, Security and Mission Services and which NASA spent more than $3 billion on in 2024. The budget proposal seeks to cut that by more than $1 billion, saying it will do so through streamlining NASA center operations, maintenance and other services.

“It pays for people who work across the other directorates. It’s sort of a general fund paying for activities across programs,” French said of that part of the budget. A cut of the magnitude proposed, he argued, “can only be accomplished by a completely different organization model for NASA itself.”

What that model would look like is not clear, but he noted it would involve fewer people. “When a 30% cut is proposed there, the only way that happens in a year is [losing] people.”

Job losses would likely go far beyond mission support. A $6 billion cut would be the equivalent of 30,000 jobs among NASA civil servants and contractors, MacDonald noted. That’s on top of the roughly 5% of NASA employees who have already left through deferred resignations. “That’s people who were living the dream, working on space science, working on space hardware, who under this budget would no longer be working on it.”

That potential exodus worries people in industry given memories of what happened after the end of the Apollo program and, later, the Space Shuttle.

“We’ve been through these transitions before,” said Dan Dumbacher, former executive director of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, during the Coalition for Deep Space Exploration’s panel.

“We hurt our workforce and our industrial base because of the uncertainty” in NASA’s future direction, he said. “We’ve seen repeatedly through the major transitions of the space program that, once we lose the workforce and even key parts of the industrial base, they do not come back.”

Crisis as opportunity

Even those worried about the impacts of the proposed budget on NASA recognize that the proposal does provide an opportunity to reform an agency they view as sluggish and, perhaps, not able to effectively compete with China and its own lunar ambitions.

“Reform is needed. We don’t want to continue with the status quo. The urgency needs to be increased,” Dumbacher said. “We need to find ways to do this in a way that takes advantage of the commercial capabilities that have been developed and apply them as rapidly as possible.”

“What does NASA look like in the future?” Garretson asked.

He envisioned one where the agency has a “central mission” and relies on commercial services to carry that out, modeled on the COTS program that developed commercial cargo services for the ISS.

“I hope to see something like a lunar COTS program that is incentivizing infrastructure,” he said.

“The old phrase is, ‘Never waste a good crisis,’ and I think there is no way to look at this budget and not see that it will create a type of crisis at NASA,” said MacDonald. “There are huge opportunities in this. I think it will require significant and difficult decisions by agency leaders over the years to come.”

“If the opportunity to make serious reforms is taken,” he said, “There is a new NASA that can emerge out of this that can leverage commercial capabilities, do business in leaner ways. It can ultimately create a future where NASA, over its next 50 years, is still doing amazing things.”

This article first appeared in the June 2025 issue of SpaceNews Magazine.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly