Now Reading: Earth from Space: East Kalimantan, Borneo

-

01

Earth from Space: East Kalimantan, Borneo

Earth from Space: East Kalimantan, Borneo

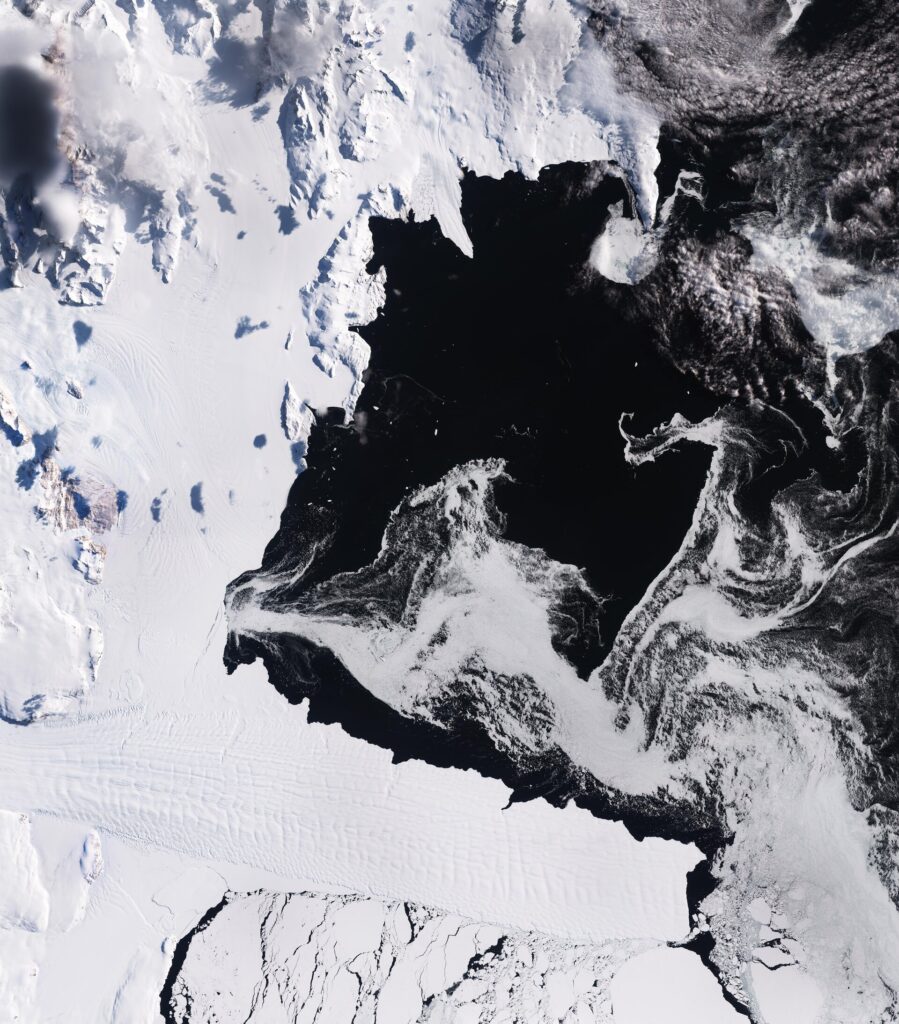

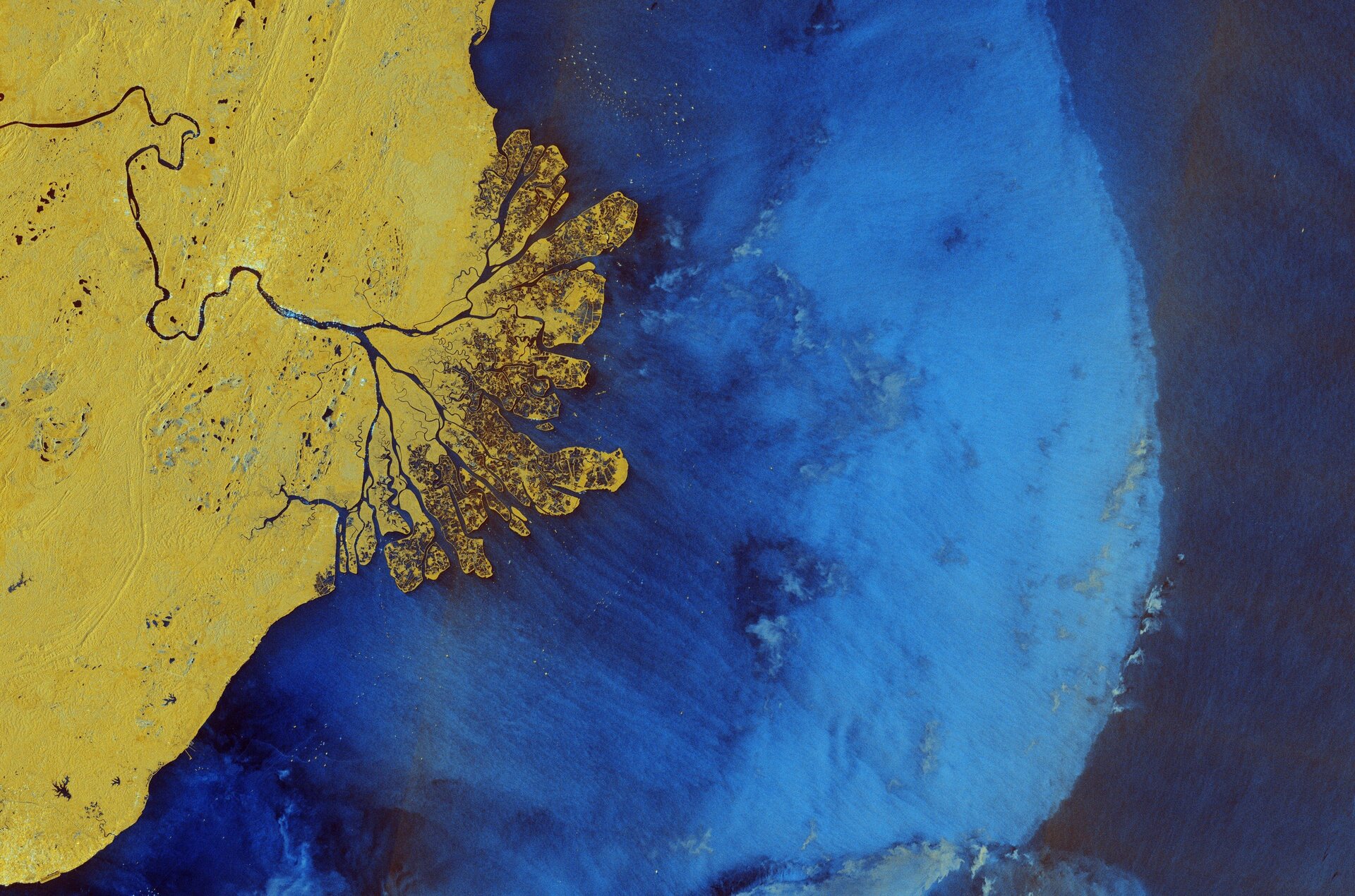

Copernicus Sentinel-1 captured this image over part of eastern Borneo, a tropical island in Southeast Asia.

Zoom in or click on the circles to explore this image at its full resolution.

Borneo, the world’s third largest island, is shared between Brunei, Malaysia and Indonesia. The area pictured here covers part of the East Kalimantan province in Indonesia, with the Makassar Strait to the east, a narrow passage in the west-central Pacific Ocean.

This radar image is from 31 March 2025, it is in false-colour and in ‘dual polarisation’ horizontal and vertical radar pulses. Compared to a single acquisition, this dual mode provides more detailed and complementary information about Earth’s surface. Different colours represent different types of land cover, such as yellow for dense vegetation and forests and dark blue for water.

Here, the land is dominated by forests, dotted with numerous small lakes appearing as dark blue spots. Brighter zones suggest built-up areas, mainly located along the course of the Mahakam River, which runs across the image. The capital of the province, Samarinda, can be seen on the northern bank of the river. Radar reflections from the ships stand out like shining jewels in the dark water of the river, as well as the sea.

The Mahakam River fans out into a labyrinth of distributaries before emptying into the Makassar Strait through a large and complex delta. The area alternates between agriculture and aquaculture, particularly shrimp farming, and extensive wetlands dominated by mangrove ecosystems. Zooming in, aquaculture structures can be seen in dark blue.

Varying colours of the seawater are caused by different atmospheric fronts and wind conditions, with stronger winds on the left in the lighter zone, and calmer conditions on the right.

Distinct greenish patches visible on the ocean surface, especially within the lighter blue area, are ‘rain cells’ – distinct areas of rainfall within a larger precipitation system. As we can see in the image, these cells can range in size, from small, localised showers to larger, more extensive rainfall events. As rain cells are easy to spot using satellite radar, scientists also exploit these images to monitor the weather.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly