Now Reading: The administration’s anti-consensus Mars plan will fail

-

01

The administration’s anti-consensus Mars plan will fail

The administration’s anti-consensus Mars plan will fail

The White House’s FY 2026 budget request for NASA proposes a radical shift in the agency’s direction, proposing extinction-level cuts to space science, severe cuts in other program areas and a dramatic pivot of human spaceflight focus to Mars.

I don’t know if the cuts will ultimately occur, but I am confident in the following: As proposed, the new humans-to-Mars initiative will fail.

This is not a judgment on the technical or funding challenges required for a successful humans-to-Mars mission, though they are legion. Instead, the failure will be downstream of politics. Any attempt to launch a generational space effort on a foundation of destruction and discord will be doomed from the start. This budget does not build the consensus necessary to carry the program forward in the next presidential term; rather, it breaks it.

Enduring space policy requires consensus. It is the essential element that sustains activities that exceed election cycles. The Artemis program is a testament to this principle. During the first Trump administration, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine, despite a difficult confirmation, built the bipartisan and bicameral support necessary for a serious return to the moon effort, aided by the strategic moves by the National Space Council and a growing NASA budget. The result was the first human lunar exploration program to survive a presidential transition since Apollo.

These lessons from the first term have apparently been discarded. On a late Friday afternoon, absent any public engagement and with little more than perfunctory congressional outreach, the administration released a NASA budget proposal unprecedented in the agency’s history.

The budget proposes a rapid pivot of human spaceflight from Artemis to Mars, retiring SLS and Orion and immediately ending Gateway. Details of lunar activities after Artemis 3 functionally disappear. Nearly $1 billion is provided for Mars-related activities, growing into the billions after Artemis 3. This could have been an exciting moment to build upon the success of the Artemis coalition, but instead, any positives of the Mars proposal are dwarfed by the breadth of draconian cuts levied against the agency.

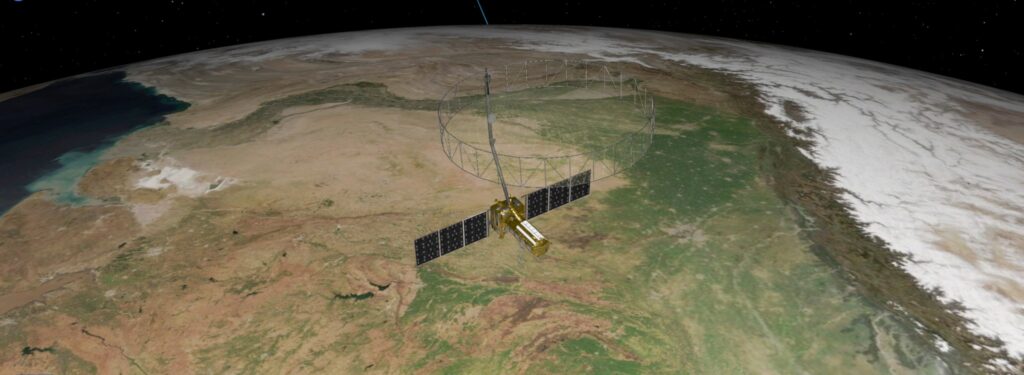

At a nearly 25% reduction, the budget is the largest single-year cut ever proposed in the agency’s history. Science is gutted by 47%, wiping out more than a third of NASA’s flight projects while slashing research funding for students and scientists around the country. It terminates critical technology and infrastructure programs (even those valuable for Mars) such as nuclear propulsion, Plutonium-238 production and active data relay satellites at Mars now. It cuts NASA’s staffing to levels not seen since 1960, abandons more than a dozen joint projects with allies and cedes the future of space science to China.

Given the scale of change outlined in this budget, one would imagine the administration making a concerted effort to build the coalition necessary to ensure its success, to assuage commercial and international partners about their investments in lunar capabilities, to engage the scientific community about the opportunities at Mars, and to ensure constituencies around the country see how they could participate in this new direction. But this has not happened. Instead, the day after this proposal was released, the president withdrew his nominee for NASA Administrator, leaving the agency rudderless at the very moment it needed to sell a new vision.

The backlash was as swift as it was predictable. Within a week, Ted Cruz (R-TX) had already moved to restore funding for SLS-enabled Artemis 4 and 5 missions, Gateway and the International Space Station — all programs the White House budget cancels or defunds. A bipartisan coalition in the House of Representatives, led by the Planetary Science Caucus, garnered more than 80 co-signatories calling for a restoration of NASA science. Industry, scientific and public outreach organizations alike have all resolutely rejected this proposal. The public response has been overwhelmingly negative, with The Planetary Society alone facilitating nearly 45,000 messages of opposition to Congress from all 50 states and 108 countries in the two weeks since the budget proposal was released.

Coordinated efforts to positively support or defend this budget, notably, remain absent.

There are two launch windows to Mars remaining in this administration. For this Mars project to succeed, future presidential administrations and congresses will be required to carry this effort forward; the choice is up to them. If the administration is serious about this Mars goal, it must ensure a coalition is in place to shepherd this transition. But a project borne from such destruction, absent any honest effort at consensus, will face serious backlash.

If the next administration is a Democratic one, will the lack of outreach and the destruction of activities in democratic states and districts engender support for this effort, or undermine it? Will commercial companies seeking private investment be helped or hurt by an impulsive shift to Mars, when that shift lacks the assurance of long-term commitments required to make their business case to investors? And, should the next president be a fellow Republican, will they also find Mars compelling enough to support? Or, when inheriting an uncertain and divisive program, would they find it easier to simply abandon the effort? In any future scenario, this Mars effort, as proposed, will face severe political challenges in as little as a year and a half, when a new Congress is sworn in. Orbital mechanics doesn’t adhere to short-term political timelines.

My organization, The Planetary Society (and I personally), very much want to see humans explore Mars. It is because we want this goal that we are so concerned with this proposal. To associate Mars exploration with the devastation of American space science, to burden the effort with enmity, to tie it to the alienation of our allies and partners, is to doom the effort to failure. Mars deserves better.

This is the reality: If the price of a human Mars program is the loss of NASA’s global leadership in space science, it will fail. If the price of Mars is the dynamiting of the bipartisan consensus behind Artemis and NASA more generally, it will fail.

Instead of providing a unifying, long-term goal for the nation, this misguided budget engenders division. The tragedy is made worse by the fact that, in so doing, the administration is effectively sabotaging its own stated goal, ignoring the lessons learned from building Artemis in its first term.

The act of sending humans to Mars should reflect the best of ourselves, a projection of our ideals of cooperation, commitment, and tenacity. It should embrace scientific goals and build stronger alliances. It should serve a clear national interest. The 2026 budget plan does none of this. It is an act of sabotage and, ironically, of self-sabotage. Its legacy will not be boots on Mars, merely a lingering societal regret at throwing away so much, so quickly, to achieve so little.

Casey Dreier is the Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society, an independent non-profit public membership organization.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these op-eds are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits