Now Reading: Trump’s dispute with Musk shows the danger of private monopolies in space

-

01

Trump’s dispute with Musk shows the danger of private monopolies in space

Trump’s dispute with Musk shows the danger of private monopolies in space

The world recently watched an argument unfold on X between Elon Musk and Donald Trump. It was a surreal exchange, featuring one of the richest men ever to have lived threatening to pull his spacecraft from NASA over a political disagreement. Some onlookers will have enjoyed it. For others, it will have been little more than background noise. But it pointed to something that’s worth taking seriously: one person can pull the plug on America’s entire crewed spaceflight program.

NASA relies on SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station. After the Boeing debacle, no other American vehicle is able to do it. That means that the United States is only ever one political (or personal) disagreement away from losing access to low Earth orbit. This isn’t about Elon Musk or Donald Trump as people. My point is neither personal nor professional. It’s about the structure of the system: critical national infrastructure surely can’t be left to the whims of private individuals, however gifted or wealthy they might be.

This connects to a broader issue, which is that governments both in the U.S. and across Europe make themselves vulnerable by leaning too heavily on private monopolies. We’ve seen this in launch services with SpaceX; Starlink with connectivity; Palantir with data and decision systems. Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud dominate cloud infrastructure. This is dangerous — not because those companies are bad actors, but because it’s risky to rely too heavily on just a handful of firms to carry out important tasks.

The irony is that innovation is booming. Europe and the U.S. are home to a new generation of space and defense startups that are lean, fast, bold and creative. These “new space” firms are building everything from synthetic aperture radar satellite constellations to optical ground stations. With effective drone countermeasures in development, they’re creating the advanced materials that protect them from being taken out by electromagnetic interference — something vital to the Ukrainian war effort, particularly in the absence of continued U.S. support.

Peter Thiel, a longtime collaborator of Elon Musk, is famous for “saying that competition is for losers.” We can’t blame SpaceX or AWS or Palantir for market dominance: every company wants market dominance. But we can ask questions about procurement — particularly in Europe. Very often, the bigger companies remain dominant not because they have the best products or are the most innovative, but because they have lobbying power, a public profile and history behind them. Often, they swallow up potential competition before it has a chance to grow or secure a contract. And yet the most innovative companies are invariably younger, smaller, more vulnerable and more willing to take risks. Taking risks is the essence of entrepreneurship and innovation, and that’s exactly what Europe needs.

There are real, practical consequences for these monopolies. For one, space overlaps heavily with defense. In fact, many of the companies serving both sectors, like my own, are dual-use: they have both civilian and military applications. For example, SpaceX has helped launch military payloads, such as the German SARah-2 and SARah-3 radar satellites. If Elon Musk were to decide one day that he no longer wanted to help launch European satellites, then Europe’s dreams of rearmament and strategic autonomy would be at grave risk: I’ve been told by European policymakers that the continent needs to be ready to repel an invasion within 18 months. Continued, free access to space is an essential part of that military readiness.

Diversification is therefore key. We need to see Europe’s defense decision-makers proactively reaching out to the smaller, newer, more innovative companies, and resisting the temptation to do what they’ve always done: funnel money to a handful of larger players. Bureaucracy and barriers to competition need, at least, a serious rethink. Investors must overcome the squeamishness of investing in defense. And doors across the continent need to be opened to the companies building the technology of the future. On the startup side, we need to see smaller companies build up their lobbying power, form relationships with the bigger contractors, join or create associations to increase their visibility and make themselves heard through clear, loud communication with the government, investors, the media and the wider public.

Europe (perhaps, the industry on the whole), also needs a broader cultural shift. Space isn’t the Wild West, nor is it a playground for billionaires. It’s infrastructure, transportation, trade, communications, disaster relief, security. It underpins much of modern life. Beyond defense, increasing competition in space will have benefits across the board, boosting productivity and sustainability at a time when both are sorely needed. We wouldn’t accept relying on a handful of monopolies for food or fuel. We should treat space similarly.

What might that look like? Passing a space-specific law could help to regulate the market, though this is risky because Europe tends to overregulate. We could boost funding for both upstream and downstream technology developers to strengthen independence. Focusing on dual-use applications and dual-use companies could kill two birds with one stone, supporting both economic growth and national or regional security at the same time. Continental supply chains could be established to ensure resilience, particularly at times of upheaval and uncertainty. And we could promote public-private partnerships for emerging companies to make sure those private companies aren’t bulldozed by the monopolies and preferred players before they have a chance to get going.

It would be easy to dismiss the Trump-Musk dispute as little more than two powerful men jostling for superiority, and many have done that. But look more closely, and it sheds light on a problem that we’ve largely been ignoring: that we are, at the moment, relying far too heavily on a small number of players to carry out a range of crucial functions. At a volatile time — geopolitically, militarily, economically and with regard to the climate — we just don’t have that luxury.

Robert Brüll, is the CEO of FibreCoat, which manufactures super-resistant, radiation-shielding materials with applications in the space and defense industries.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these op-eds are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

01From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

02Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth

03How New NASA, India Earth Satellite NISAR Will See Earth -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

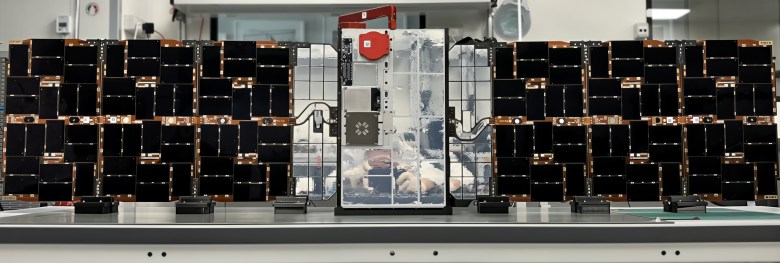

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly