Now Reading: Will asteroid 2024 YR4 hit the Moon?

-

01

Will asteroid 2024 YR4 hit the Moon?

Will asteroid 2024 YR4 hit the Moon?

27/06/2025

311 views

5 likes

Asteroid 2024 YR4 made headlines earlier this year when its probability of impacting Earth in 2032 rose as high as 3%. While an Earth impact has now been ruled out, the asteroid’s story continues.

The final glimpse of the asteroid as it faded out of view of humankind’s most powerful telescopes left it with a 4% chance of colliding with the Moon on 22 December 2032.

The likelihood of a lunar impact will now remain stable until the asteroid returns to view in mid-2028. In this FAQ, find out why we are left with this lingering uncertainty and how ESA’s planned NEOMIR space telescope will help us avoid similar situations in the future.

What is asteroid 2024 YR4?

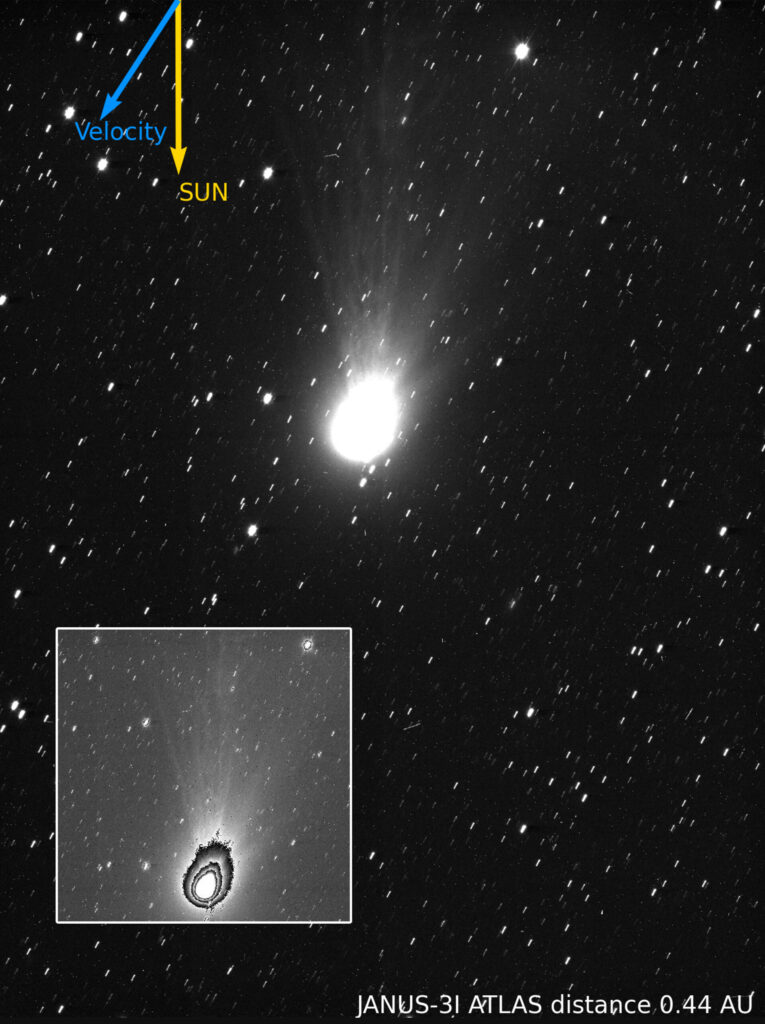

Asteroid 2024 YR4 was discovered on 27 December 2024 at the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) telescope in Río Hurtado, Chile.

Shortly after its discovery, automated asteroid warning systems determined that the object had a small chance of potentially impacting Earth on 22 December 2032.

The asteroid is between 53 and 67 metres in diameter. An asteroid of this size impacts Earth on average only once every few thousand years and would cause severe damage to a city or region.

Follow-up observations saw the chance of impact rise to around 3%. As a result, the asteroid shot to the top of ESA’s asteroid risk list and captured global attention as it became the first asteroid to trigger a coordinated international planetary defence response.

Additional observations made over the next few months, including those made using the James Webb Space Telescope, allowed astronomers to more accurately measure the asteroid’s orbit around the Sun.

By March 2025, they had enough information to rule out an Earth impact in 2032.

Why did we not detect 2024 YR4 sooner?

2024 YR4 was first discovered two days after it had already passed its closest point to Earth. It was not detected sooner because it approached Earth from the day side of the planet, from a region of the sky hidden by the bright light of the Sun.

This region of the sky is hidden from the view of ground-based optical telescopes and is a blind spot for asteroid warning systems.

The significance of this blind spot was made clear on 15 February 2013, when the Chelyabinsk meteor, a 20-metre, 13 000-tonne asteroid, struck the atmosphere over the Ural Mountains in Russia during the middle of the day. The resulting blast damaged thousands of buildings, and roughly 1500 people were injured by shards of glass.

Could we have detected 2024 YR4 sooner?

ESA’s Near-Earth Object Mission in the InfraRed (NEOMIR) satellite, planned for launch in the early 2030s, will cover this important blind spot.

NEOMIR will be equipped with an infrared telescope and positioned at the first Sun-Earth Lagrange Point. By relying on infrared light, rather than visible light, NEOMIR can spot asteroids in a region of the sky much closer to the Sun. It will repeatedly scan this region for the thermal signatures of asteroids approaching Earth that are at least 20 metres across – like 2024 YR4 and the Chelyabinsk meteor.

“We looked into how NEOMIR would have performed in this situation, and the simulations surprised even us,” says Richard Moissl, Head of ESA’s Planetary Defence Office.

“NEOMIR would have detected asteroid 2024 YR4 about a month earlier than ground-based telescopes did. This would have given astronomers more time to study the asteroid’s trajectory and allowed them to much sooner rule out any chance of Earth impact in 2032.”

“As an infrared telescope, like Webb, NEOMIR would have also immediately given us a much better estimate for the asteroid’s size, which is very important for assessing the significance of the hazard.”

Will asteroid 2024 YR4 impact the Moon?

By March 2025, astronomers had ruled out an Earth impact in 2032. However, the final observations of the asteroid failed to rule out another intriguing possibility: a lunar impact.

The probability that asteroid 2024 YR4 will strike the Moon on 22 December 2032 is now approximately 4%, and this probability was still slowly rising as the asteroid faded out of view.

However, this means that there is a 96% chance that the asteroid will not impact the Moon.

When will we know for sure?

We are left with an interesting situation: there is now a 60 m asteroid with a 4% chance of hitting the Moon in 2032. As the asteroid is now too far away to study any further, this probability will remain unchanged until it returns into view in June 2028.

When it does return into view, new observations will be made and it will not take long for astronomers to confidently determine whether the asteroid will, or much more likely, will not, hit the Moon on 22 December 2032.

What will happen if the asteroid hits the Moon?

“A lunar impact remains unlikely, and no one knows what the exact effects would be,” says Richard Moissl.

“It is a very rare event for an asteroid this large to impact the Moon – and it is rarer still that we know about it in advance. The impact would likely be visible from Earth, and so scientists will be very excited by the prospect of observing and analysing it. I am sure that detailed computational simulations will be done over the next few years.”

“It would certainly leave a new crater on the surface. However, we wouldn’t be able to accurately predict in advance how much material would be thrown into space, or whether any would reach Earth.”

In the coming years, as humankind looks to establish a prolonged presence at the Moon, monitoring space for objects that could strike Earth’s natural satellite will become increasingly important.

Small objects burn up in Earth’s atmosphere as meteors, but the Moon lacks this shield. Objects just tens of centimetres in size could pose a significant hazard to astronauts and lunar infrastructure.

What else is ESA doing to improve Europe’s planetary defence capabilities?

The discovery of asteroid 2024 YR4 made it clear that time is of the essence when it comes to asteroid detection. In cases like that of 2024 YR4, the later an asteroid is detected, the less time is available for follow-up observations before it fades from view.

Decision makers need as much information as possible when considering potential mitigation strategies, such as deflection missions or evacuation plans: they do not want to be left with an uncertain but significant chance of Earth impact for multiple years.

By keeping watch for asteroids approaching Earth from the direction of the Sun, ESA’s NEOMIR space telescope will fill an important blind spot in our current asteroid detection systems and significantly improve our preparedness for future hazards similar to 2024 YR4.

Follow the links below to find out more about ESA’s other Planetary Defence activities, such as the Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre (NEOCC); the Flyeye asteroid survey telescopes; the Hera mission, which will turn asteroid deflection into a well understood and repeatable technique for planetary defence; and the Ramses mission to intercept and explore the infamous asteroid Apophis as it safely passes close to Earth in 2029.

ESA’s Planetary Defence Office is part of the Agency’s Space Safety Programme. The Programme works to monitor and mitigate hazards in or from space, protecting our Pale Blue Dot, its inhabitants, and the vital infrastructure on Earth and in space on which we have come to depend.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly