Now Reading: A martian butterfly flaps its wings

-

01

A martian butterfly flaps its wings

A martian butterfly flaps its wings

03/12/2025

225 views

2 likes

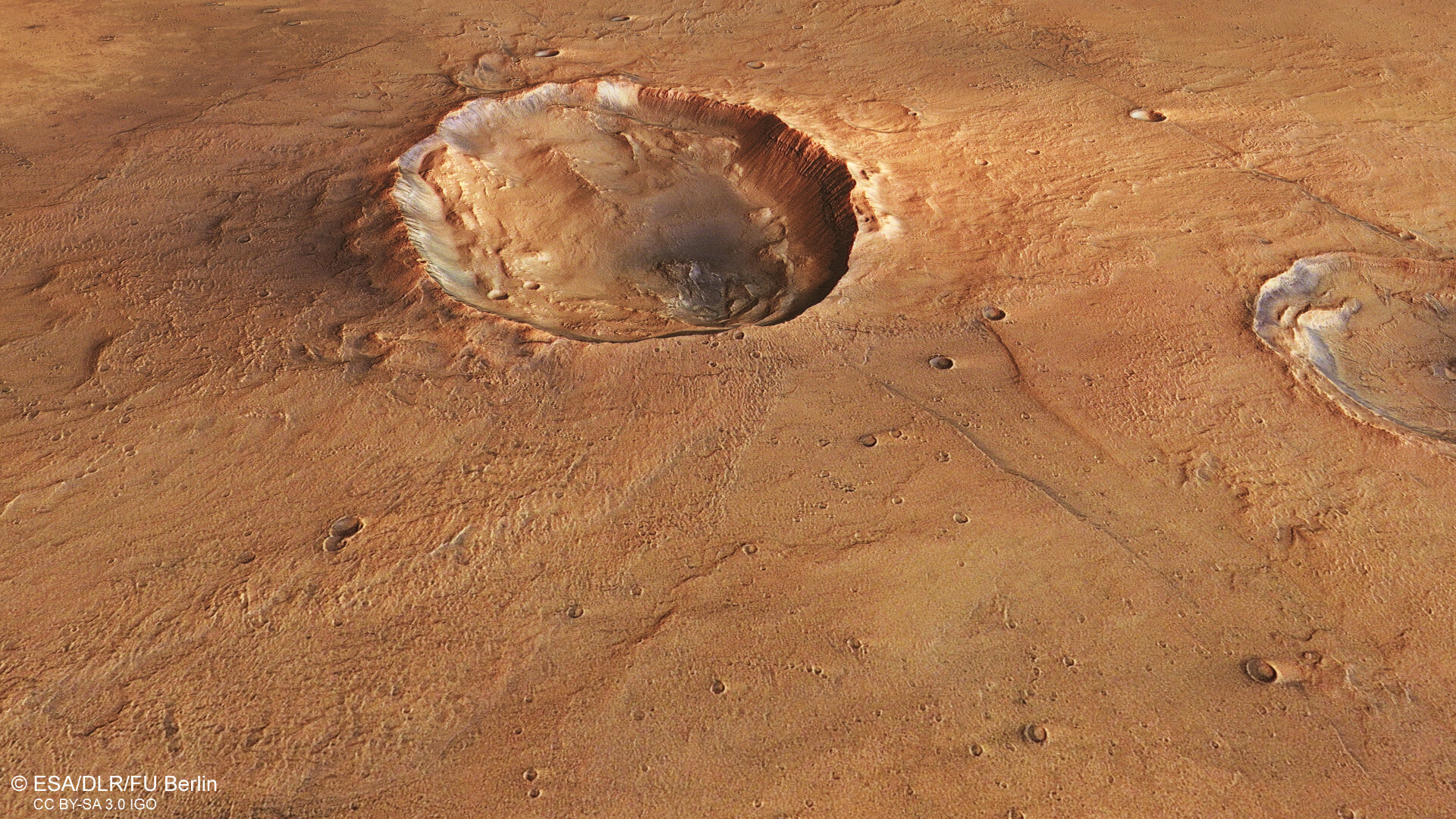

Is it an insect? A strange fossil? An otherworldly eye, or even a walnut? No, it’s an intriguing kind of martian butterfly spotted by ESA’s Mars Express.

Insects aren’t commonplace on Mars, so it’s no surprise that this is no butterfly as we know it. It’s actually a kind of crater, formed as a space rock hurtled towards the Red Planet and collided with its red-brown surface.

The collision caused two distinct lobes of material to be flung outwards to the crater’s north and south, creating two outstretched ‘wings’ of raised ground. The wings of this particular butterfly crater are rather undefined and irregular, but can be seen extending to the lower left and upper right of the main walnut-esque crater shown here.

This crater measures roughly 20 km from east to west and 15 km from north to south. It lies in the Idaeus Fossae region of Mars, in the planet’s northern lowlands. The crater and its wings can be seen in more detail in a new video produced by the Mars Express HRSC team, which simulates what it would be like to slowly circle it – and its surroundings – from above.

Another example of a butterfly crater, this time in Mars’s southern highlands, is highlighted in Mars Express’s images of Hesperia Planum.

Unusual shapes

Typically we would expect material to be thrown outwards in all directions by a crater-causing collision. However, we know that the space rock that sculpted this martian butterfly came in at a low, shallow angle, resulting in the interesting and atypical shapes seen here: the butterfly’s ‘body’ – the main crater itself – is unusually oval in shape, and the wings are irregular.

Some of the debris forming the wings (mostly seen just above the crater, and labelled in the image below – which is annotated if you click on it) also appears smoother and more rounded, almost reminiscent of a mudslide. This indicates that it has mixed with water or ice from under the surface of Mars – ice that perhaps melted during the crater impact itself. This is known more technically as ‘fluidised’ material, and is seen often on Mars.

Crumpling lava

The butterfly crater may draw the eye, but it’s far from the only feature of interest here. The rest of the frame is largely flat, lending the spotlight to a cluster of steep, flat-topped rocky outcrops – known as mesas – to the left (shown in the zoom in perspective view below). The higher patches of ground here have been slowly worn away, with the remaining hills being those that have managed to resist erosion over time.

The mesas stand out clearly against the tan-coloured surroundings due to the layers of dark material that have been exposed along their edges. As on Earth, this material is probably rich in magnesium and iron, and created by volcanism. This region likely saw quite a bit of volcanism in the past, with lava and ash deposits building up over time and being buried by other material through the years.

Signs of lava can be seen here in ‘wrinkle ridges’: folded patterns that likely formed here when lava flowed, cooled, and contracted, causing the surface to crumple.

The bigger picture

This patch of Mars gets its name from Idaeus Fossae, a broad system of valleys lying a few kilometres to the west (top) of frame. One such valley can be seen to the right (north) of the image here below, and other less prominent valleys and ridges are scattered across the frame.

As labelled in the associated context map, most of Idaeus Fossae is found just next to a sharp, 2-km-high cliff-face marking the edge of the Tempe Terra plateau.

Mars Express has been capturing and exploring Mars’s many landscapes since it launched in 2003. The orbiter has mapped the planet’s surface at unprecedented resolution, in colour, and in three dimensions for over two decades now, returning insights that have drastically changed our understanding of our planetary neighbour (read more about Mars Express and its findings here).

The Mars Express High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) was developed and is operated by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR). The systematic processing of the camera data took place at the DLR Institute of Space Research in Berlin-Adlershof. The working group of Planetary Science and Remote Sensing at Freie Universität Berlin used the data to create the image products shown here.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

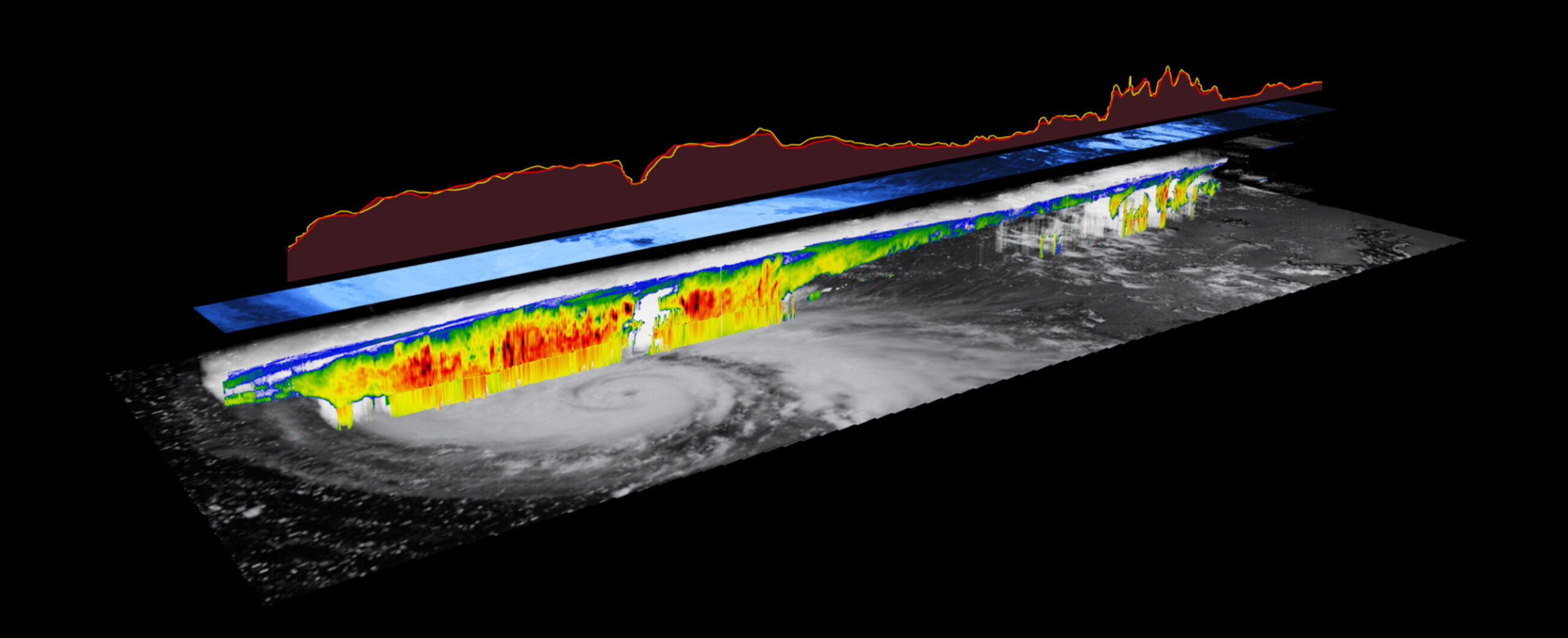

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

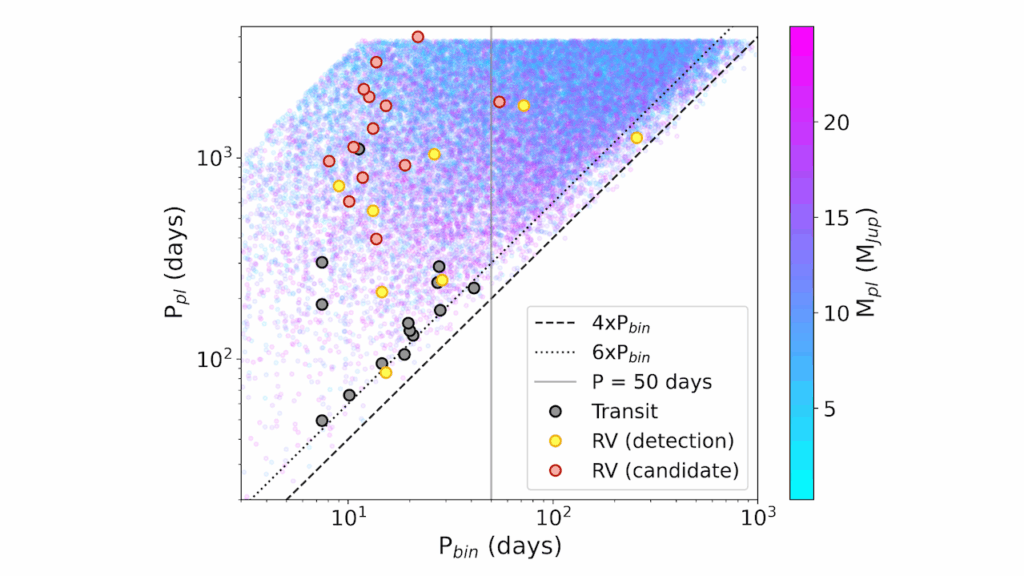

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly