Now Reading: A New Industrial Age in Orbit

-

01

A New Industrial Age in Orbit

A New Industrial Age in Orbit

For decades, building a space mission meant a hard choice between two imperfect models.

The first was the traditional prime: capable, proven, and thorough, but slow and expensive. Customers paid hundreds of millions, waited years, and in return got a fully integrated, bespoke spacecraft.

The second model arrived with the much-touted promises of “new space”: smaller satellites, lower-cost launches, modular buses, and plug-and-play payloads that would spark a revolution in orbit. But those promises have only been partially realized. Early hopes of democratizing space ran up against a simple truth: integration is hard. New space offered components at lower cost, but it still sold standardized buses, not missions. The burden of integrating spacecraft, payloads, software, networks, and operations remained exactly where it had always been: on the customer.

“There’s a huge amount of complexity in buying disparate pieces off the market and trying to make them work together,” says Muon Co-Founder and CEO Jonny Dyer. “…You’re not buying a mission. You’re buying a parts list and a problem.”

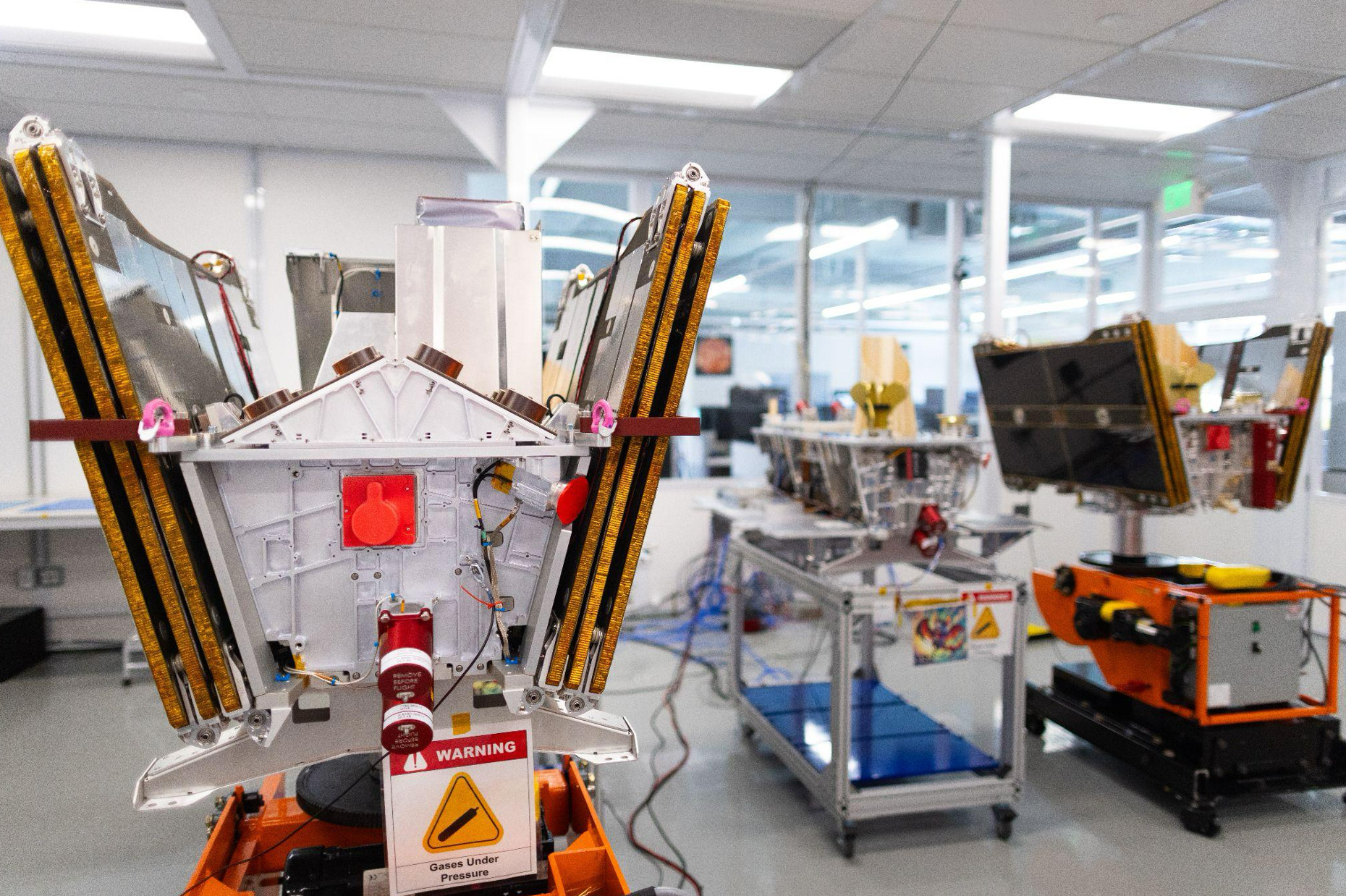

A new path was clearly needed, and the industry is finally building one. Muon’s Mission Foundry is among those leading the shift, aligning design, deployment, and operations for mission-specific constellations across Earth observation, telecommunications, and national security. By simulating and digitally designing an entire mission (payloads, buses, orbits, computing, networks, data distribution, and operations) into a single, vertically integrated stack, what was once painstaking and manual, becomes repeatable, scalable, and ultimately industrial. This shift is not just a product of technology. It’s also reflective of a change in mindset, where expectations surrounding access are moving toward engineered systems that can operate at scale.

“There’s a huge amount of complexity in buying disparate pieces off the market and trying to make them work together,” says Muon Space Co-Founder and CEO Jonny Dyer. “Spacecraft, software, networks, operations—none of it was designed as an integrated stack. You’re not buying a mission. You’re buying a parts list and a problem.”

Across the industry, this dynamic played out repeatedly. Organizations with promising concepts would discover that the broader ecosystem still required them to stitch together low-volume components that were never designed to operate as a coherent system. “What a lot of organizations found,” Dyer says, “is that even though the parts existed, the integration and operations burden still fell entirely on them.” Instead of simply selecting a bus, a payload, and a communications system, teams had to build internal engineering groups to reconcile mismatched interfaces, data pipelines, software stacks, and power requirements. “The assumption was that the smallsat revolution had made this easier,” he notes. “But in practice, many missions realized they were still doing most of the hard integration work themselves.”

The experience revealed an important industry-wide lesson: customers didn’t necessarily need more tailored components so much as they needed a complete system capable of delivering fully integrated operations.

That, it turns out, is not a unique problem, particularly in how we handle growing volumes of information back on Earth.

“If you think about the way a modern data center is built—companies like Google and Amazon don’t just assemble components, they design and build their own servers, networks, even chips—there’s a vertically integrated stack they control from silicon to software,” Dyer explains. “The Mission Foundry is the equivalent of that in space.”

By treating space missions the way cloud providers treat data centers, i.e. standardized, interoperable building blocks that can be rapidly assembled, Muon is effectively turning orbital operations into making space missions as repeatable as large scale server deployments. The Foundry integrates what the industry has historically kept separate: constellation modeling and mission design, reconfigurable spacecraft platforms, onboard compute and storage, global terrestrial and in-space networks, and end-to-end operations. Muon’s M-Class and XL-Class platforms can be configured rapidly with different CPU/GPU capacity, power systems, and instrument interfaces, while software-defined radios and optional Starlink laser terminals dramatically increase downlink capacity—”50 times greater capacity down,” Dyer notes.

The result is transformative.

Instead of designing satellites, operations, data systems, and ground connections separately, the Foundry focuses on delivering mission-ready constellations from the outset.

“Muon’s Mission Foundry gets customer constellations designed, launched, and into operation faster, more affordably, and with higher operational performance than has traditionally been possible,” says Muon President Gregory Smirin—a shift with real-world implications.

For instance, wildfire detection missions like FireSat – a system capable of spotting fires as small as a one-car garage – are pushing toward hourly global coverage, with the goal of revisiting the same location every 15 to 20 minutes. This “revisit time” can only be achieved with satellites working in concert. Whether it’s monitoring natural disasters or providing critical data across agriculture, energy, logistics, insurance, and other commercial sectors, these missions all demand rapid deployment, high-duty cycles, and predictable operations—not multi-year development timelines.

Commodity platforms can be mass-produced, but without tight integration across hardware, software, and operations, they underdeliver on duty cycles, downlink, and mission effectiveness. The Foundry’s vertical integration solves this: every spacecraft is optimized not just for launch, but for sustained, high-performance operations at scale.

“Muon’s Mission Foundry gets customer constellations designed, launched, and into operation faster, more affordably, and with higher operational performance than has traditionally been possible,” says Muon President Gregory Smirin.

“There’s a fragility to small numbers,” Dyer notes. “But as the scale of the industry grows, you inherently get a lot of reliability from economies of scale and better statistical quality control.”

Orbits effectively become production environments: networks are shared, compute nodes live on-orbit, constellations communicate with each other, satellites tap into common infrastructure, and new entrants can build atop what already exists.

“You can foresee layers of infrastructure that get built in space,” he adds, pointing to the array of networks, mobility needs between orbits, power sources, compute storage, and serving nodes. “These will aggregate over time and build on themselves.”

In many ways, the Foundry mirrors the evolution of terrestrial internet infrastructure: once fiber had blanketed continents, entire industries emerged. Low-cost launch and proliferating platforms like Starlink are creating similar conditions in orbit. And by handling tasks like plotting orbits and managing data, the Foundry makes space missions accessible to organizations that once considered them out of reach. Orbital data centers can plug into existing systems; startups can focus on building sensors; logistics and mobility companies can use ready-made networks; governments can launch constellations faster; and big tech can explore space-based computing without reinventing the mission. Space begins to look modular, interoperable, and predictable.

In short, it becomes industrial.

For Muon especially, this isn’t hypothetical, having launched its first spacecraft in 2023. The company has four successful missions under its belt, and over twice that number of launches planned for next year. Its integrated data system is capable of 5 terabytes per day via radio frequency (RF), with Starlink crosslinks multiplying capacity roughly tenfold. That launch tempo, and the iteration speed it enables, feels less like traditional aerospace and more like cloud software releases.

And that’s the point.

Ultimately, the Mission Foundry is a blueprint for a new industrial paradigm built on scale, standardization, and vertical integration. When future companies deploy, much of the foundational work, network layers, integration stack, modeling engines, and operations frameworks, will already be done. The idea is to shape space’s next era, and help formulate the story of Earth’s newest factory floor, which rests miles above us.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly