Now Reading: Carbon Mapper and tracking super pollutants

-

01

Carbon Mapper and tracking super pollutants

Carbon Mapper and tracking super pollutants

In this week’s episode of Space Minds, host David Ariosto speaks with Riley Duren, CEO of Carbon Mapper and veteran of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Duren discusses how his nonprofit is harnessing cutting-edge satellite technology to track methane and carbon dioxide emissions—the “super pollutants” driving climate change. He explains Carbon Mapper’s mission to make greenhouse gas data visible and actionable, the technical innovations behind their hyperspectral satellites, and the incentives that motivate companies to reduce emissions.

Drawing from his decades at NASA, Duren highlights the shift from risk-averse institutional missions to an agile, public-private partnership model, and why moving fast is essential in the fight against climate change.

Show notes and transcript

Click here for Notes and Transcript

Time Markers

00:00 – Episode introduction

00:25 – Welcome

01:00 – What is Carbon Mapper?

02:20 – How do you do it?

03:29 – Be timely

04:42 – Corporate buy-in

07:04 – Governments

10:44 – The potential

11:54 – Super emitters

13:51 – Situational awareness

16:54 – Public-private partnerships

18:22 – R&D

19:28 – Bottlenecks

22:44 – Cultural differences

26:36 – Can’t move slowly

Transcript – Riley Duren Conversation

David Ariosto – Riley Duren, Chief Executive Officer at Carbon Mapper, and a long time veteran of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It is, it is so good to have you on the on the pod.

Riley Duren – Thanks, David. It’s great to be here.

David Ariosto – Yeah. So I was, I was really looking forward to this conversation, because you kind of have this interesting nexus of the symbiosis between these NASA level systems of engineering and nonprofit climate advocacy. And so you kind of have this blend of this hard science and tech innovation and, you know, aspirations for real world impact. So I think that’s probably a good place to start this what, is Carbon Mapper? Describe, to me, what, where this came from, the genesis of it and its mission.

Riley Duren – Sure, so Carbon Mapper is a non profit organization that we founded about five years ago in Pasadena, with a public good mission to make methane and carbon dioxide data accessible and actionable. And we care about methane and carbon dioxide because they’re the two chief global warming drivers. They’re super pollutants that are driving warming of the planet and all the negative impacts that that causes. And so our theory of change is if you can make the data visible, visible and usable to a wide range of stakeholders, then they can take action to reduce those emissions. Excuse me, because these greenhouse gasses are otherwise invisible, and the motivation for creating Carbon Mapper sprang out of over two decades of my work at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, where we worked on developing monitoring systems, global monitoring systems for greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide and methane, and a lot of lessons along the way, both technical and programmatic, regarding barriers to deploying those systems at scale. Yeah,

David Ariosto – So how do you do it? I mean, we’re talking about remote sensing. We’re talking about sort of increasing capabilities on orbit, whether it’s just in terms of imaging spectroscopy or sort of even some of the data and the processing that kind of happens on orbit. But you know what? What’s the approach here, not only from sort of a technical perspective, but identifying where, because I imagine you have methane leaks all over the place, but you know, some of these super emitters are sort of like, maybe where you you focus your targets a little bit more, right?

Riley Duren – So if you zoom out, and I’ll apply my system engineering background here to look at kind of the end to end challenge is our theory of change is if, if the goal is to reduce methane emissions and carbon dioxide emissions, methane in particular, then you need to do three things. Number one is you have to be able to detect the majority of the high emission sources on the planet. We often call them super emitters. So that’s a question of completeness. How much can you observe with your monitoring system? And secondly is accessibility. Can you make the data available in formats that people can use in a timely fashion. And third…

David Ariosto – …is fast enough, is, I think, is the question there too, right? What’s that? If it’s fast enough, right? Latency with this data, then maybe it’s not That’s right.

Riley Duren – Speed is critical. It has to be within the interest horizon of people who can act on it. And thirdly, is responsiveness. Is can you create narratives and information out of that data that incentivizes people to use it and act on it? And that’s a really complex and exciting topic, given how diverse these sources of methane are on the planet, but in terms of how we do. That first piece the monitoring is we use remote sensing developed at NASA over several decades that basically can detect methane and CO two at the scale of an individual facility. And the way to think about it is like having a camera, Except unlike a normal camera that sees in three colors, red, green, blue, like the human eye, our cameras actually see almost 500 colors, and those colors range from the visible wavelengths into the infrared, and it’s the infrared wavelengths where we can detect invisible greenhouse gasses.

David Ariosto – Right getting buy in at the corporate level, I think, would probably be sort of a hurdle in all this. And I was just sort of digging around in least in terms of what you do. It’s like, it seems like part of the value prop for the corporate side of this is avoiding product loss. And like, I wonder how those conversations kind of manifest. Because, if we’re just purely talking about doing good in the world, the nature of like reducing methane emissions in terms of just the overall health of the planet, that that is a very sort of nebulous kind of construct that you might go to to a specific company with, whereas, if you’re going to this with, like, Hey, you’re losing product here, you need to sort this out. Walk me through that. Because, I guess my question is, like, it almost seems like you would need relationships with those companies directly.

Riley Duren – Yeah. I mean, it’s a fascinating topic. Is the topic of incentives. You know, why act on the data to reduce emissions? And so there are several you mentioned, one product laws. If you’re an oil and gas company and you’re producing natural gas as a product, then methane leaks are the equivalent of venting your profits into the atmosphere. That is product loss, right? And that’s the easiest motivation to understand. But there are other motivations, for example, competitiveness in global markets, because there are jurisdictions around the planet. The European Union is one of them that is working to establish standards to reduce the intensity or the lossiness of natural gas supply chains, and so that’s creating a differentiated market.

You know, like oil and gas producing countries that have dirtier natural gas, lossier natural gas, will be at a disadvantage to countries that can demonstrate that they have lower emissions. So that’s a market based incentive. In addition to product loss, other motivations include local health considerations. I mean, methane is usually not the only thing coming out of the ground, particularly with oil and gas operations. In some cases, there can be CO emitted toxics, and that can be often a very important health concern for local communities, both governments and citizens, as well as the people operating the facilities who are being exposed to those potential toxic so there are a range of motivations to tackle this, in addition to product laws.

David Ariosto – You know, I remember years ago, I was covering the oil and gas industry. I was up in the Bakken region, up in North Dakota. And I mean, first of all, I’ve never been that cold in my life. But second, you know, in terms of some of these, these, these oil and gas operations, fracking operations, you’d see sort of these, these flares that that would happen, crawl across the landscape, and they’re literally just just, you know, there’s a byproduct of some of those operations you’re flaring off in the natural gas.

Now, that’s somewhat different, but, but it falls, I think, within the same, same category. And the argument at the time was that, like, you know, just the investment in terms of the infrastructure wasn’t quite there, from a dollars and cents perspective to kind of address this. And so you just have this almost taste in the air as you’re driving around, and you see these just flares, light up, light up the countryside. And I wonder, like, at that level, if a company is aware of this and still doing and still sort of venting, is that like it? It strikes me like this is where partnerships come come in, and this is where, you know, working with sort of local and federal governments come in. Because it, it strikes me like what you’re doing is providing the data for addressing these problems, but still has to be a wherewithal to address them in some capacity, right?

Riley Duren – Yep, so yeah, that’s the flare example is a really good one, because it highlights really two avenues for action. So the first one is that when oil and gas companies, and this also happens with landfills, right it When? When facility operators use flares. That is, they combust the methane to burn it off and convert it to CO two, many times. There are assumptions that that is very efficient. In other words, the EPA standard numbers assume very high, completely in the high 90% combustion efficiencies, meaning most of the methane is converted to CO two in practice, a lot of times those flares are pretty inefficient, and combustion efficiencies can be 90% or lower, and that’s a lot of into gas that could be avoided if you improve the efficiencies of a flare. So that’s something that companies can address.

Through investments, but we also find, and this goes back with our studies we’ve done with aircraft and satellites for almost a decade now, is that in many cases, it’s not an efficiency question, it’s just the pilot light has gone out. So the straight up malfunctions, and we actually find, in many cases, when we flag this for companies, they’re unaware that the pilot light has gone out. I mean, it’s literally just venting methane gas. And so there’s some very low tech, low cost things people can do to avoid things like that and so and then to your point about partnerships, we actually find that where we have the biggest success rate with companies finding and fixing leaks is when we invest effort in reaching out directly to the companies or through local air regulators who have relationships with many of the operators. And what we find in those cases that roughly 50% of the cases that we report a methane emission, the operator reports that they didn’t know about it, and they’re able to quickly fix it, and that’s voluntary action. And so I call this the Good Neighbor approach. You know, if you’re a good neighbor, you let someone know when they’ve got an oil or gas, when they’ve got a gas leak or a water leak on their property. And the same thing applies here, is if you can let people know that they’ve got a methane event that they didn’t know about, many times, they’ll take action voluntarily.

David Ariosto – And the real numbers behind this too. I remember, I remember, I think that you saw something that, that there makes you represent, like, 3% reductions in terms of states overall, so methane emissions, at least in terms of the bigger states. I mean is that, first of all, is that, is that accurate in terms of the what the numbers that I’m just quoting right now? But more importantly, like the cumulative effect of this? It’s not just a sort of a piecemeal approach, right?

Riley Duren – The potential is there and just into to be clear, if you, if you zoom out and look at where methane emissions come from, writ large, on earth, roughly half of methane emissions come from natural sources like wetlands and high latitude sources. The other half comes from human activity. And of that human activity, a lot of this, actually, I lost my train of thought. Can you ask the question again? Sorry.

David Ariosto – Yeah, I’m just, I’m guessing, trying to get a sense of, like, you know, you talk about individual companies. We talk about sort of individual oil and gas fields. Talk about, like, you know, different state approaches and local and federal regulators. But it but, but more in the sense of the cumulative effect of what that looks like.

Riley Duren – Yeah, so let, let me explain the term super emitter for a minute. It gets thrown around a lot. So scientific studies have shown, now for some years, using surface based measurements, aircraft and satellites, that there tends to be a relatively small fraction of the equipment out there, and this is true for oil and gas. It’s true for coal, it’s true for landfills. It’s even true for agriculture, where a small number of facilities are responsible for a disproportionate amount of emissions. So a typical number in say, the state of California, is less than 1% of the infrastructure is responsible for between a third and a half of the total methane emissions in the state, and so we call the small fraction of large It’s remarkable. Now to be clear, this varies a lot by region, and it has to do with, you know, whether a region’s methane emissions are dominated by oil and gas versus, say, landfills or say agriculture, and those numbers vary a lot.

But what we’ve noticed over the years with our studies across different us, oil and gas and and coal producing regions, as well as other parts of the world, is between 20 and 60% of the regional emissions come from the small number of super emitting facilities. And so what that means is there’s a potential for really large reductions at a fairly small number of facilities, if you can identify where they are quickly. That’s that is the kind of the general theory of change around Carbon Mapper. And to be clear, this doesn’t mean that this is the only thing that we need to do to tackle methane emissions. I mean, there’s a need for a portfolio of responses, and that includes going after a lot of the small emissions everywhere, through investments in the infrastructure and practices. But it also means doing this go after the big leaks quickly, because we can have a fast impact that way.

David Ariosto – Well, in that sense, also just the nature of, and I’m speculating here, so correct me if I’m wrong, but the nature of how you build constellation infrastructure, and I would, I would imagine these are geosynchronous satellites that are focusing although I could be wrong on that, but it almost strikes me is that if you, if you hone in on on areas almost similar to the way the defense industry sort of looks at missile sites in the security landscape. You know, you might be looking at Super emitters in terms of oil and gas facilities. You don’t necessarily need the 1000s and 1000s of satellites on orbit that could be operating low Earth orbit. But, you know, I could be wrong here in terms of, like your business model. But I just, I wonder. Because you’ve identified major problem areas and recurring major major problem areas, having that that focus specific to those areas might make your job a little bit easier.

Riley Duren – Yeah, so actually, I can draw an example from the weather service to explain this, right? So you know, we’ve all become accustomed over the last several decades to have at our fingertips, in a moment’s notice, detailed weather information. I mean, you can get on an app on your smartphone today, radar images, satellite images, you know, weather forecast alerts. And it really is stunning, the capability that’s there that we I think we often take for granted, and that’s the result of decades of investments and billions of dollars in federal investments, government investments, and building constellations of weather satellites. Well, think about what those weather satellites do.

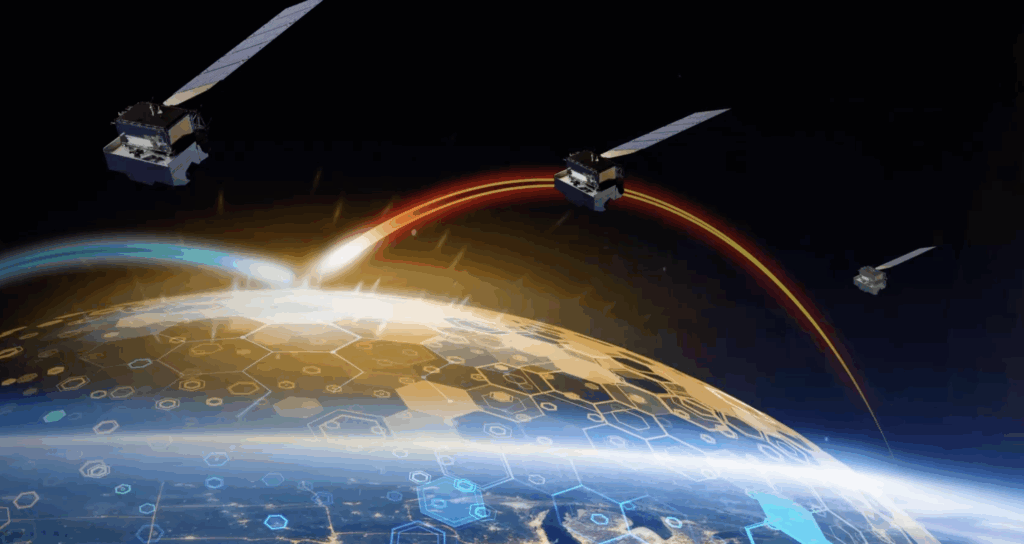

They’re a combination of satellites that provide continuous monitoring over the entire continent, as well as satellites that can provide higher resolution images. And the same is true for greenhouse gas monitoring, and that is what we’re trying to do at carbonmapper is part of a broader ecosystem of observing systems. And just to clarify it, our own observing system, which involves the Tanager satellites that our commercial partner planet is launching are actually satellites in low Earth orbit. They’re a constellation. That constellation, when we get enough of them in orbit, we’ll be able to provide daily or more frequent monitoring, just like you know, some of the polar orbiting weather satellites. But additionally, there are other satellites, for example, operated by the European Space Agency or the Japanese Space Agency that look at the whole planet, and they provide more synoptic information at higher at coarser resolution. So it’s this system of systems approach. It’s an ecosystem of satellites out there to which we contribute that really provide us with situational awareness both at the fine scale, what’s happening at individual facilities at 30 meter resolution, as well as the broader picture at continental scale. And that’s, again, my analogy to the Weather Service, except this is more of a methane and carbon Weather Service.

David Ariosto – Yeah, so low Earth orbit constellations certainly do two factor and certainly a more pronounced way than I was giving credit, but you mentioned planet in terms of partnerships and in terms of the constellations and like, what you’re what you’re looking at. I wonder if you give us an update, like where, where that stands, in terms of deployment of satellites and sort of existing partnerships and forward looking notions of where you where you hope to be.

Riley Duren – Yeah. So one of the more interesting things about this program we’ve built at Carbon Mapper is a public, private partnership that we started shortly after the nonprofit was created five years ago. And that partnership includes Planet Labs, our commercial partner, and NASA JPL. And the way this worked is that the the instrument technology, this remote sensing technology that we’re using, which was originally developed at NASA at JPL. And so what Carbon Mapper did is we funded JPL to build the first instrument and transfer the know how on how to replicate that instrument to Planet Labs. So it’s basically a technology transfer program, and then planet is applying their agile aerospace model to building and operating many of these satellites, which they call tanagers. So planet successfully launched Tanager one about a year ago. We just had our one year anniversary last weekend, and it’s operating beautifully, and they’re on track to launch three more of these satellites as we speak.

David Ariosto – Isn’t that it interesting though. A lot of this, this R&D that happens at the government level, at sort of these high levels, things have has, it just has a way of, kind of trickling out into the commercial sector and that it be operationalized.

Riley Duren – Actually, I actually, my experience is, is that you use the right word, trickling out. And I’ll specifically this program. Things were, I think, left to its own, would have moved too slowly. And that is that the the Imaging Spectrometer technology is something that NASA has been using on aircraft, but getting it into space has been a really long road. And so because we can’t afford as a species to wait around on addressing climate change, Carbon Mapper stepped in with the support of our our philanthropy donors, to really accelerate this. And so it really was by, you know, funding, specifically funding the technology transfer, was intended to really accelerate this. Because I feel like had we waited for this to more organically trickle out, we could still be waiting 10 years from now to make this happen.

David Ariosto – Yeah, that’s interesting. In the context of the technology itself, you’ve talked about, sort of the variety of different colors, and, you know, ultraviolet sensing, and you know the the nature of, sort of all this, all this new information that that’s coming on orbit. Yeah, and then you sort of look at the just like the nature of how to get this information back, and I imagine you’re using, you know, increasing amounts of machine learning and AI and you know how to sort of process this data. And I just, I wonder if, with this explosion of data, do you see bottlenecks that are starting to emerge in terms of these things, or do you are you exploring sort of different approaches in terms of, like, how to get that information back? Because, like, all this capacity is great, but you still got to get it down to earth right since that that makes it actionable to use your words.

Riley Duren – No, I actually think one of the things I’m proud of working with our partners and planet and JPL is that all of the data is brought down. There’s there’s the infrastructure, the machinery, the satellites, the ground stations, the backhaul, the ground data systems, both at Planet and at Carbon Mapper, who collectively are responsible for the data pipeline is very robust, and all of that data comes down. I think what you’re poking at is, where are the bottlenecks and getting the maximum utility out of the data, and the…

David Ariosto – …Latency is for part of that equation.

Riley Duren – So yeah, well I mean, again, on the on the latency front, you know, we routinely now process data within 12 hours of it, of it being collected, and we’re able to, actually, you know, to notify subscribers within, you know, less than 24 hours in many cases that we detected methane, which is really important if you’re trying to do this leak detection thing. But, but, but to your point about, you know about blockers. I think the the opportunity and the challenge is getting the most out of this data, because one of the one of the theory of change, things we did with with Carbon Mapper and the Tanager satellites, is create a system that’s not just focused on methane and CO two, because that would be very much a one trick pony, is that we deliberately pick a technology. It’s called hyper spectral imaging that covers everything from the visible into the short wave infrared, literally hundreds of channels of information.

And the number of applications of that data is not limitless, but it’s a large number, probably in the hundreds of applications, not just methane and CO two things like agriculture, water quality, fire, fuel loads, biodiversity, and so in mineralogy and so on. And so there’s a huge rich data set there that is yet to be fully mined by the universe of people who could use it. And so I think that’s where advanced machine learning and deep learning and new algorithms are just starting to scratch the surface on this data set. I mean, Carbon Mapper’s mining the heck out of it for methane and CO two. But there are many other applications that have not yet unfolded.

David Ariosto – That’s interesting. That’s fascinating. I want to just take a little bit of a step back in terms of the nature of your story and your kind of journey throughout this whole process. Because, I mean, you started carbon map right? You obviously saw a need. Clearly. There is a need for these types of things, not only just in terms of the broader health of the planet, but how this responsiveness can help individual companies on a sort of a product loss and sort of even just a sort of a human health perspective or crop growth perspective. But you spent a lot of your career the things 27 years at JPL Jet Propulsion Laboratory there in Pasadena. And I wonder, like, what the difference is? Like the cultural difference coming from, from, you know, near three decades at at NASA and the institution, and, you know, the heck of a reputation that shop has in terms of everything that’s achieved. You know, Mars landing notwithstanding, but what’s it like now in terms of, like, pushing into this frontier of where you’re you’re calling the shots, and you have maybe less, you may have less of that sort of institutional inertia that you have to contend with, but, you know, don’t necessarily have the same sort of support systems that might have been imbibed within age old institutions. So I’m just curious, like, how you’re adapting to that, and frankly, what made you do it?

Riley Duren – Yeah, well, I mean, that’s a great question. You know, it’s on some in some ways, it’s not as different as you might think. And that is, I do believe JPL is a truly special place. It is, you know, objectively, a national gem in terms of its ability to innovate and do things that that others dream of doing. What I what I learned at JPL was a, I don’t know, I fearlessness to tackle things that are difficult and not to be afraid to, quote, break things. But there is a limit to that. And I think you know to your point when you’re building the first of a kind one, of one and one in a universe type space mission. Um. But the risk posture has to be fairly conservative, because the costs of failure is so high. And so if you think back to the early days of NASA, back when every other launch vehicle was exploding on the pad, the agency adopted a mindset of, we’re going to build two or three of everything, because, you know, we need to launch that many to get one successful.

And over the years, as the launch vehicles became more reliable, the agency began to build bigger and bigger single missions, and that that meant failure was not an option. That is part of NASA’s mantra, and there are good reasons for it, for a lot of in a lot of cases, but to your point, it does mean that there is some conservatism and risk adverseness that is appropriate when you’re just doing one so the big difference in what we’re doing now as a nonprofit and working with our commercial partner planet is basically a higher tolerance for risk, and part of that is because We the way we’ve designed the program, we’re not just launching one satellite, we’re launching many and so the risk is spread out. We don’t put all of our eggs in one basket, and it also means we’re working with funders, in this case, philanthropic donors, who also have a high risk tolerance. And if you think about where some of these people come from, their businesses and their you know, their backgrounds are in taking risk, and so that’s the big difference. Is it is a different risk posture. I think it’s appropriately higher risk. And of course, the reason why we take those risks is we need to move fast, because the challenge we’re trying to tackle doesn’t allow us to move slow.

David Ariosto – I think that’s the interesting thing about this whole sort of new iteration, sort of this, this, you know, commercial era, this Space Race, 2.0 the, you know, however you define, like, what, what we’re in right now, it’s, it’s been, one of the hallmarks, has been sort of this iterative approach in which failure is a likely option. And but there is also, you know, a cultural shift that accompanies that, that makes that okay, to some extent, provided this is a big caveat here, provided we’re not talking about human lives online, which I do think that that changes. And you know, that’s been less the purview of JPL, and sort of more the sense of, you know, Johnson Space Center and others, you know, the questions about human operations up there, but in terms of like where you’re taking this, I find this just find this just terribly exciting, terribly important, too. So thank you so much for joining us here on the pod. Riley Durham, Chief Executive Officer at Carbon Mapper, thanks so much.

Riley Duren – Thank you David, pleasure.

About Space Minds

Space Minds is a new audio and video podcast from SpaceNews that focuses on the inspiring leaders, technologies and exciting opportunities in space.

The weekly podcast features compelling interviews with scientists, founders and experts who love to talk about space, covers the news that has enthusiasts daydreaming, and engages with listeners. Join David Ariosto, Mike Gruss and journalists from the SpaceNews team for new episodes every Thursday.

Watch a new episode every Thursday on SpaceNews.com and on our YouTube, Spotify and Apple channels.

Be the first to know when new episodes drop! Enter your email, and we’ll make sure you get exclusive access to each episode as soon as it goes live!

Space Minds Podcast

“*” indicates required fields

Note: By registering, you consent to receive communications from SpaceNews and our partners.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly