Now Reading: Commercial radar satellite firm eyes role in U.S. missile defense

-

01

Commercial radar satellite firm eyes role in U.S. missile defense

Commercial radar satellite firm eyes role in U.S. missile defense

ST. LOUIS — The Trump administration’s push to modernize missile defense could open new opportunities for the commercial remote-sensing industry, according to Eric Jensen, CEO of Iceye U.S., a subsidiary of Finnish radar satellite operator Iceye.

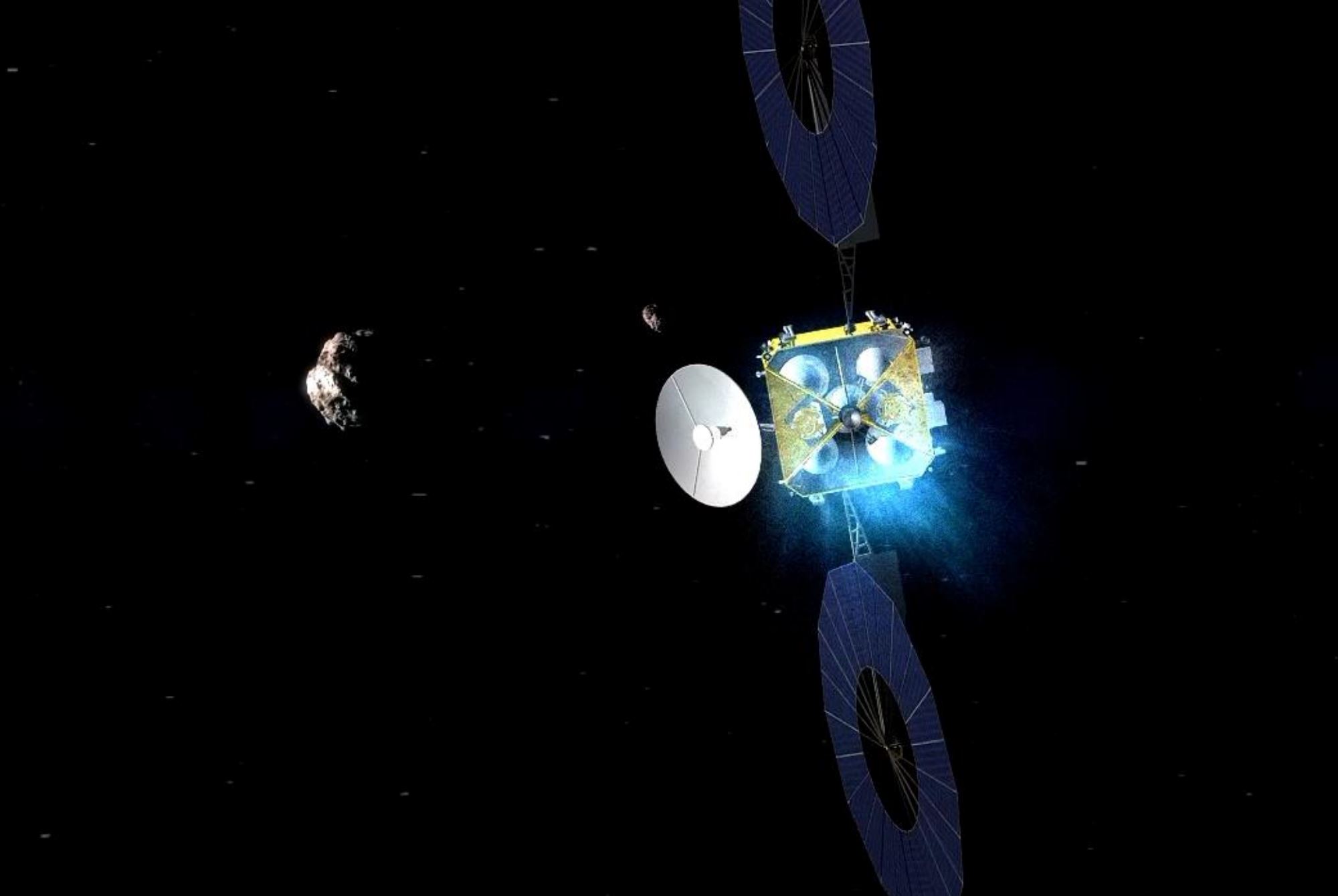

As part of the “Golden Dome for America” executive order that directs an overhaul of the U.S. missile defense architecture, the administration has emphasized greater use of commercial technologies. Jensen argues that commercial synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellites, like those deployed by Iceye, could play a supporting role alongside the infrared (IR) sensors traditionally used by the U.S. military to detect missile launches.

“We have a diverse set of sensors that are already in orbit today, providing great utility daily in operations across the world,” Jensen told SpaceNews. “And while they are not designed to meet all of the requirements that would be a part of the Golden Dome architecture, they can clearly provide an input … that would result in much better persistence, much better timeliness of information, much more accuracy.”

SAR satellites produce high-resolution images of Earth’s surface regardless of weather or lighting conditions, and are increasingly used in defense, disaster response, and environmental monitoring. Iceye operates more than 40 SAR satellites, and while the company hasn’t formally proposed their use for Golden Dome, Jensen sees a case for integrating such commercial capabilities into the Pentagon’s plans.

“The government can benefit from the fact [private companies] are all investing and developing new capabilities,” he said. “Commercial SAR could be transformative for missile defense in critical ways.”

One of those ways is “left of launch” monitoring — tracking activities that might signal preparations for a missile launch before it happens. “It’s really tough for people to hide from commercial SAR,” Jensen said. “But you want to take a layered approach.”

Jensen said Iceye is in early conversations with potential partners in the defense industry regarding Golden Dome opportunities. Meanwhile, there is uncertainty across the industry over long-term government support for commercial space services. While Congress has added funds to defense budgets for commercial satellite imagery, permanent procurement programs known as “programs of record” have yet to materialize.

Seeking long-term SAR contracts

Commercial SAR companies experienced a surge in contracts over the past three years, largely fueled by supplemental war funding directed toward support for Ukraine and Israel. That influx of short-term funding supported commercial imagery and analytics to aid in battlefield awareness and intelligence sharing. But as those emergency appropriations taper off, companies like Iceye face pressure to secure more predictable, sustained revenue streams.

Jensen said SAR companies are waiting for the U.S. government to fund commercial SAR capabilities within its base budgets.

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), which oversees U.S. satellite intelligence collection, has signed agreements to assess commercial SAR data. But so far, the agency hasn’t committed to large-scale purchases.

“The wrong thing to do is to pull the rug out once the capabilities have matured to the point where they could actually be scaled,” said Jensen. “The right thing to do is to continue to invest in a balanced way.”

He emphasized that national systems still play a critical role but said the government should also establish “long-term, multi-year contracts for commercial systems.”

Jensen acknowledged that his push for commercial SAR in the Golden Dome initiative “can seem oddly self-serving,” but said it also reflects “the great value that’s been created” by private-sector innovation.

Looking ahead, Jensen said the fiscal year 2026 defense budget will be a key indicator of how seriously the government plans to invest in commercial space assets. “From where I sit today, my view is that Congress should take a bold approach to FY26,” he said.

He noted that responsibility for commercial satellite procurement is fragmented across multiple agencies, each with separate mandates and authorities. “That has created and will perpetuate a degree of instability,” Jensen said. “At this point in time, it is going to require Congress to step in and make clear its intent.”

In fiscal year 2025, Congress earmarked $40 million for commercial surveillance, reconnaissance, and tracking services. But industry leaders remain wary of stopgap measures in place of long-term commitments.

“We’ve had the operational experience where our capabilities have been leveraged by the U.S. and allied governments in real crises around the world,” said Jensen. “However, we’ve got to keep proving it.”

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

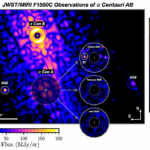

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits