Now Reading: Could the Milky Way galaxy’s supermassive black hole actually be a clump of dark matter?

-

01

Could the Milky Way galaxy’s supermassive black hole actually be a clump of dark matter?

Could the Milky Way galaxy’s supermassive black hole actually be a clump of dark matter?

New research suggests the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way is actually a tremendously massive yet compact clump of dark matter.

Scientists say this clump would exert the same gravitational effects currently attributed to the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). That includes the violent and rapid dance of stars taking place at the Galactic Center, in which so-called “S-stars” race around the compact heart of our galaxy at speeds as great as 67 million miles per hour (30,000 kilometers per second). For context, that’s around 10% of the speed of light. This dark matter clump, the team says, would also account for the orbits of the dust-shrouded bodies, or “G-sources” located in the Galactic Center.

Fermionic dark matter is proposed to be capable of forming a structure that consists of a super-dense, compact core with so much mass that it mimics a supermassive black hole with a mass equivalent to 4.6 million suns, the research team says. That core would be surrounded by a vast and diffuse halo stretching out far beyond the visible matter of the Milky Way — but acting as a single unified entity. This is a structure that other recipes of dark matter can’t replicate.

“We are not just replacing the black hole with a dark object; we are proposing that the supermassive central object and the galaxy’s dark matter halo are two manifestations of the same, continuous substance,” team member Carlos Argüelles, of the Institute of Astrophysics La Plata, said in a statement.

Seeing is believing … but what are we seeing?

The theory, proposed by Argüelles and colleagues, is strongly based on observations conducted by the European Space Agency’s star tracking mission Gaia, released as part of the project’s third data drop in June 2022.

Gaia allowed the team to precisely map the rotation and orbit of stars and gas in the outer halo of the Milky Way, revealing a slowdown of our galaxy’s rotation curve: the so-called Keplerian decline. This team thinks the Keplerian decline can be explained by the diffuse outer halo they saw, which is a factor in their model and one that, as we now know, adds support to the fermionic model of dark matter.

In the standard model of cosmology, also known as the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (LCDM) model (the best description we have of the universe), dark matter is “cold,” which means its particles move at speeds significantly slower than the speed of light.

Cold dark matter forms an extended halo tail that struggles to account for the slowdown observed by Gaia. The fermionic model, on the other hand, predicts a tighter and more compact halo tail that could cause Keplerian decline. Remember, in the Sgr A* model, dark matter at the heart of the Milky Way isn’t connected in a single structure to the outer halo, thus that tail isn’t present in this model.

“This is the first time a dark matter model has successfully bridged these vastly different scales and various object orbits, including modern rotation curve and central stars data,” Argüelles said.

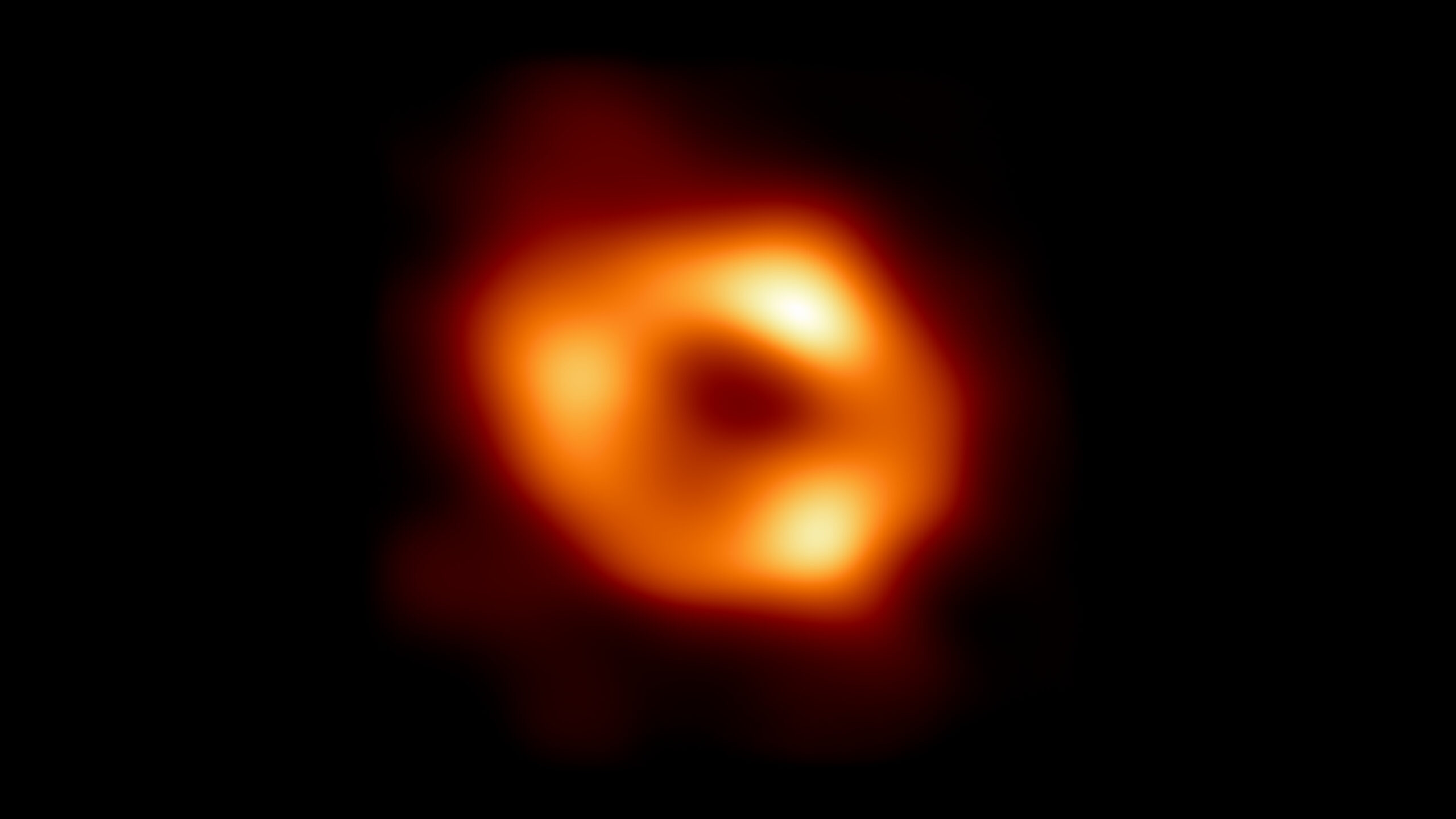

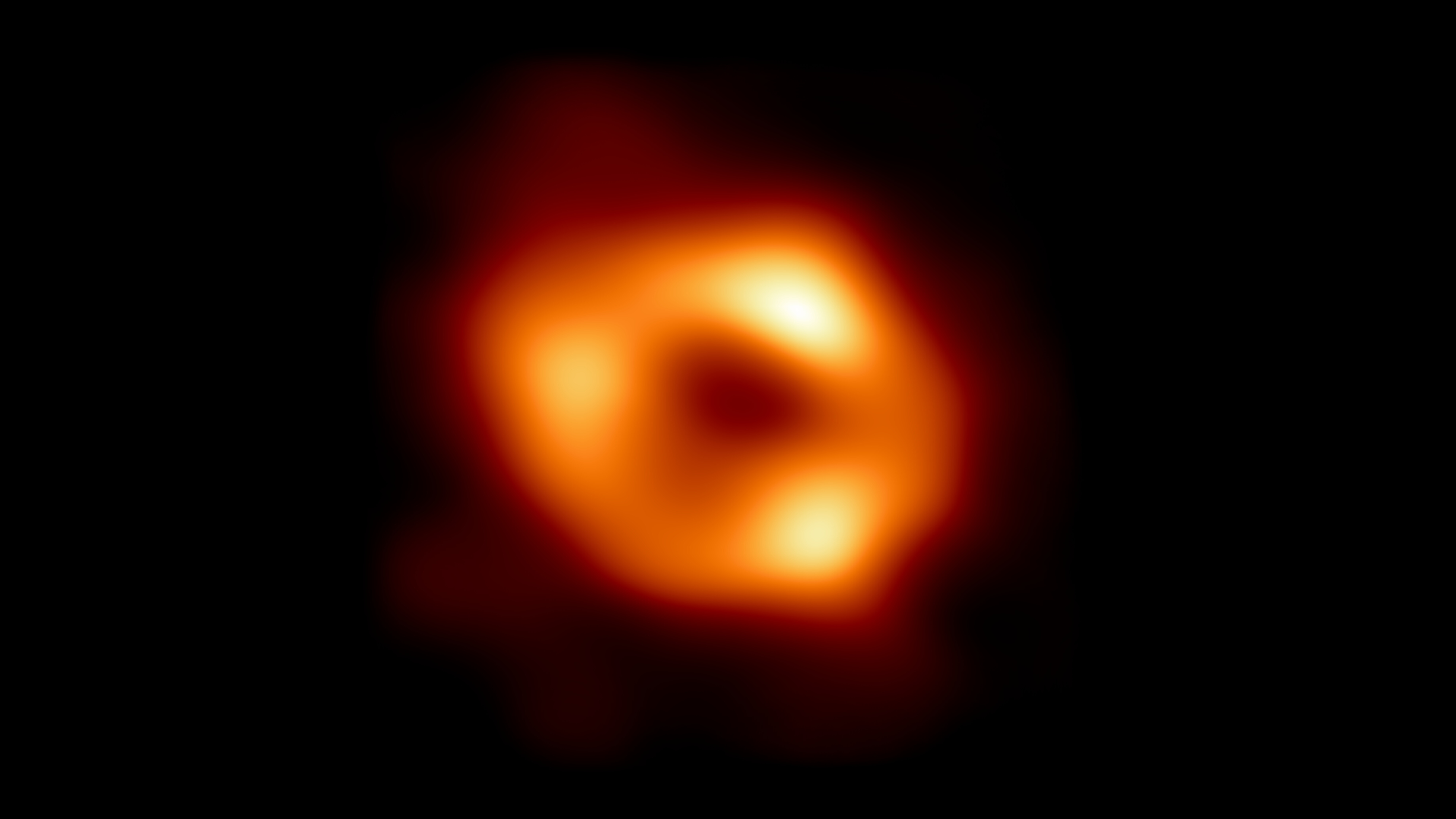

So far, so good. The theory that our galaxy may have a clump of dark matter rather than a black hole in its center appears to be fairly credible. However, there is a 4.6 million solar mass elephant in the room: namely, the image of Sgr A* captured by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) and revealed to the public in May 2022. Still, the team says their fermion dark matter model can account for this.

Before diving into that explanation, it is worth considering what we actually see when we look at the EHT image of what we all currently assume to be Sgr A*.

The glowing golden ring in this image is actually superhot matter whipping around whatever lurks at the heart of the Milky Way. What we actually see in this image isn’t a black hole at all, understandable because black holes are surrounded by a light-trapping surface called an event horizon; there’s no way we could directly see Sgr A*. What we can see, though, is the shadow the black hole casts.

Yet in 2024, researchers demonstrated that a dense core of fermionic dark matter could actually cast a shadow that is similar to that seen in the EHT image. The core would be invisible like a black hole because dark matter famously doesn’t interact with light.

“This is a pivotal point,” said team leader Valentina Crespi of the Institute of Astrophysics La Plata. “Our model not only explains the orbits of stars and the galaxy’s rotation but is also consistent with the famous ‘black hole shadow’ image. The dense dark matter core can mimic the shadow because it bends light so strongly, creating a central darkness surrounded by a bright ring.”

Though the team has statistically compared their dark matter model to the accepted model of a supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way, and the former was able to replicate the behavior of S-stars, G-sources, the structure of our galaxy and the black hole shadow, the researchers emphasize it is definitely still early days for this theory.

The team’s research does lay down a roadmap for future observations using the Very Large Telescope (VLT) to hunt for photon rings at the heart of the Milky Way, which will be present for Sgr A*, but absent if the central dominating body of our galaxy is a dense clump of dark matter.

Clearly, Sgr A* isn’t ready to relinquish its throne at the heart of the Milky Way to dark matter just yet.

The team’s research was published on Feb. 5 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS).

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

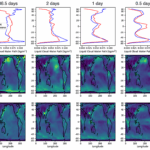

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

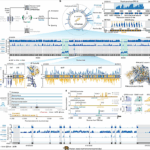

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly