Now Reading: Curiosity Blog, Sols 4593-4594: Three Layers and a Lot of Structure at Volcán Peña Blanca

-

01

Curiosity Blog, Sols 4593-4594: Three Layers and a Lot of Structure at Volcán Peña Blanca

Curiosity Blog, Sols 4593-4594: Three Layers and a Lot of Structure at Volcán Peña Blanca

4 min read

Curiosity Blog, Sols 4593-4594: Three Layers and a Lot of Structure at Volcán Peña Blanca

Written by Susanne P. Schwenzer, Professor of Planetary Mineralogy at The Open University, UK

Earth planning date: Monday, July 7, 2025

A few planning sols ago, we spotted a small ridge in the landscape ahead of us. Ridges and structures that are prominently raised above the landscape are our main target along this part of Curiosity’s traverse. There are many hypotheses on how they formed, and water is one of the likely culprits involved. That is because water reacts with the original minerals, moves the compounds around and some precipitate as minerals in the pore spaces, which is called “cement” by sedimentologists, and generally known as one mechanism to make a rock harder. It’s not the only one, so the Curiosity science team is after all the details at this time to assess whether water indeed was responsible for the more resistant nature of the ridges. Spotting one that is so clearly raised prominently above the landscape — and in easy reach of the rover, both from the distance but also from the path that leads up to it — was therefore very exciting. In addition, the fact that we get a side view of the structure as well as a top view adds to the team’s ability to read the geologic record of this area. “Outcrops,” as we call those places, are one of the most important tools for any field geologist, including Curiosity and team!

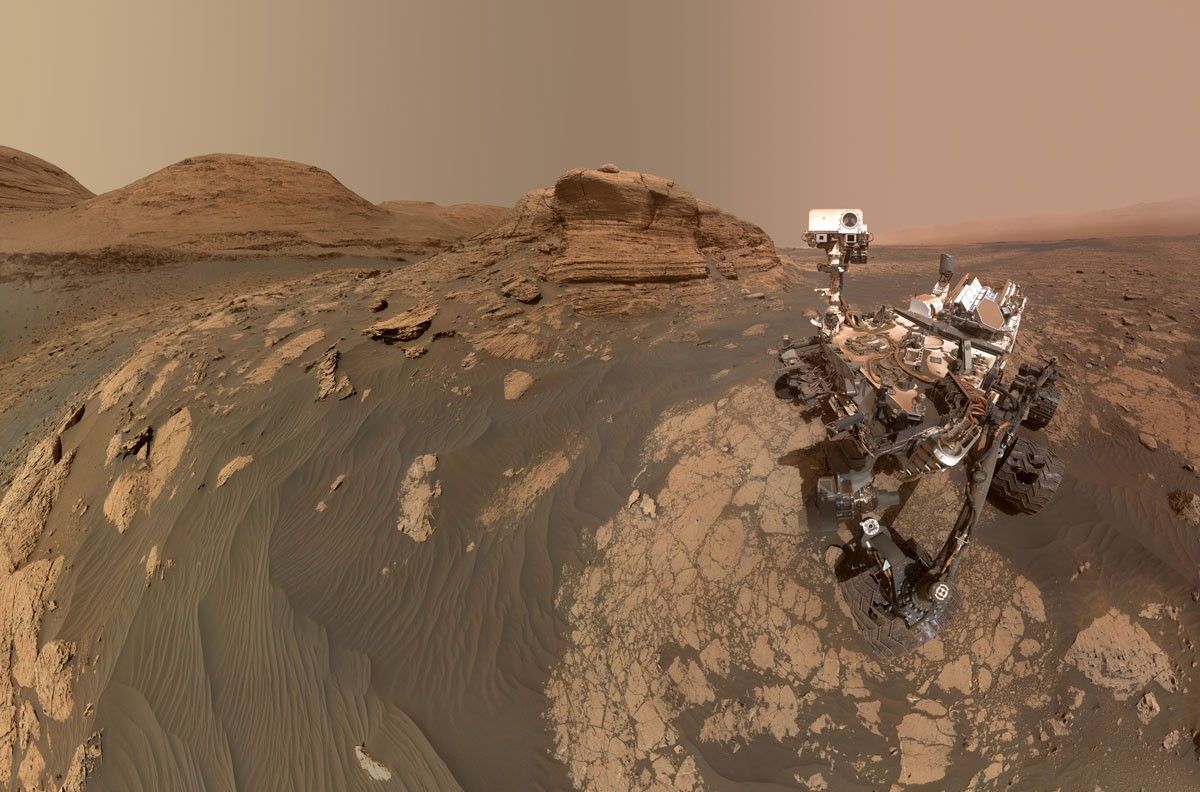

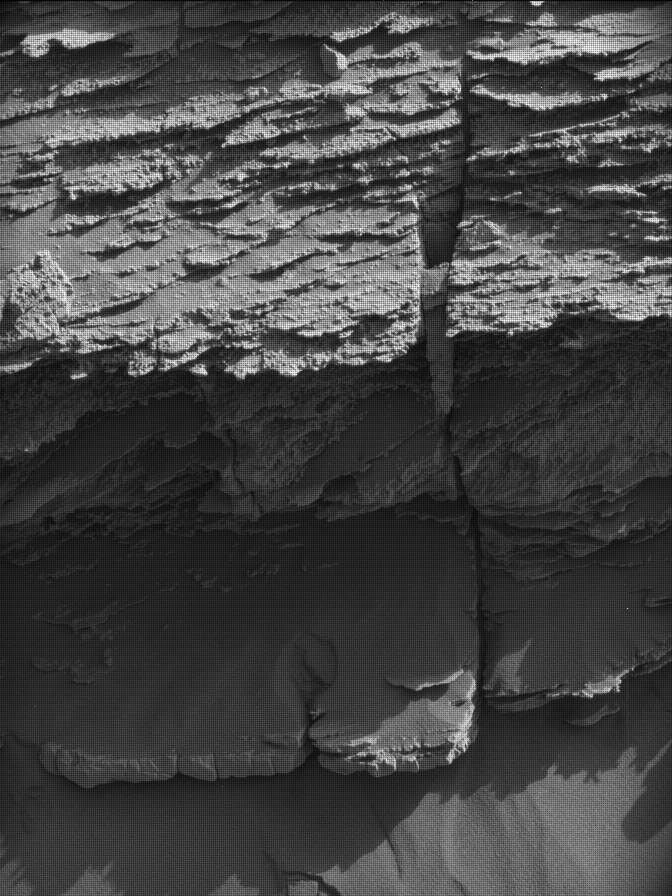

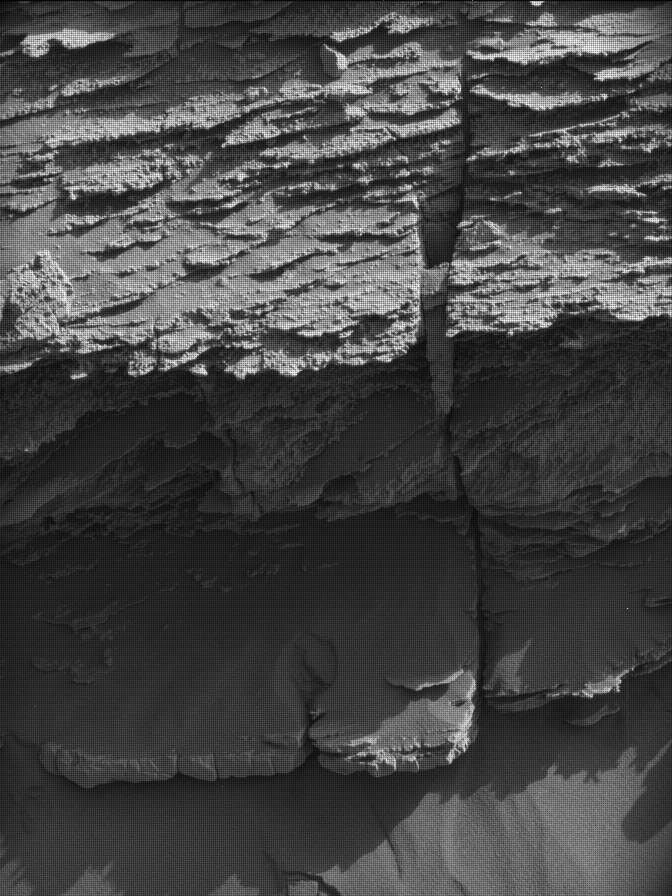

Therefore, the penultimate drive stopped about 10 meters away (about 33 feet) from the structure to get a good assessment of where exactly to direct the rover (see the blog post by my colleague Abby). You can see an example of the images Curiosity took with its Mast Camera above; if you want to see them all, they are on the raw images page (and by the time you go, there may be even more images that we took in today’s plan.

With all the information from the last parking spot, the rover drivers parked Curiosity in perfect operating distance for all instruments. In direct view of the rover was a part of Volcán Peña Blanca that shows several units; this blogger counts at least three — but I am a mineralogist, not a sedimentologist! I am really looking forward to the chemical data we will get in this plan. My sedimentologist colleagues found the different angles of smaller layers in the three bigger layers especially interesting, and will look at the high-resolution images from the MAHLI instrument very closely.

With all that in front of us, Curiosity has a very full plan. APXS will get two measurements, the target “Parinacota” is on the upper part of the outcrop and we can even clean it from the dust with the brush, aka DRT. MAHLI will get close-up images to see finer structures and maybe even individual grains. The second APXS target, called “Wila Willki,” is located in the middle part of the outcrop and will also be documented by MAHLI. The third activity of MAHLI will be a so-called dog’s-eye view of the outcrop. For this, the arm reaches very low down to align MAHLI to directly face the outcrop, to get a view of the structures and even a peek underneath some of the protruding ledges. The team is excitedly anticipating the arrival of those images. Stay tuned; you can also find them in the raw images section as soon as we have them!

ChemCam is joining in with two LIBS targets — the target “Pichu Pichu” is on the upper part of the outcrop, and the target “Tacume” is on the middle part. After this much of close up looks, ChemCam is pointing the RMI to the mid-field to look at another of the raised features in more detail and into the far distance to see the upper contact of the boxwork unit with the next unit above it. Mastcam will first join the close up looks and take a large mosaic to document all the details of Volcán Peña Blanca, and to document the LIBS targets, before looking into the distance at two places where we see small troughs around exposed bedrock.

Of course, there are also atmospheric observations in the plan; it’s aphelion cloud season and dust is always of interest. The latter is regularly monitored by atmosphere opacity experiments, and we keep searching for dust devils to understand where, how and why they form and how they move. Curiosity will be busy, and we are very much looking forward to understanding this interesting feature, which is one piece of the puzzle to understand this area we call the boxwork area.

Share

Details

Related Terms

Share

Details

Related Terms

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly