Now Reading: Don’t miss Jupiter and the moon join up in the night sky this weekend

-

01

Don’t miss Jupiter and the moon join up in the night sky this weekend

Don’t miss Jupiter and the moon join up in the night sky this weekend

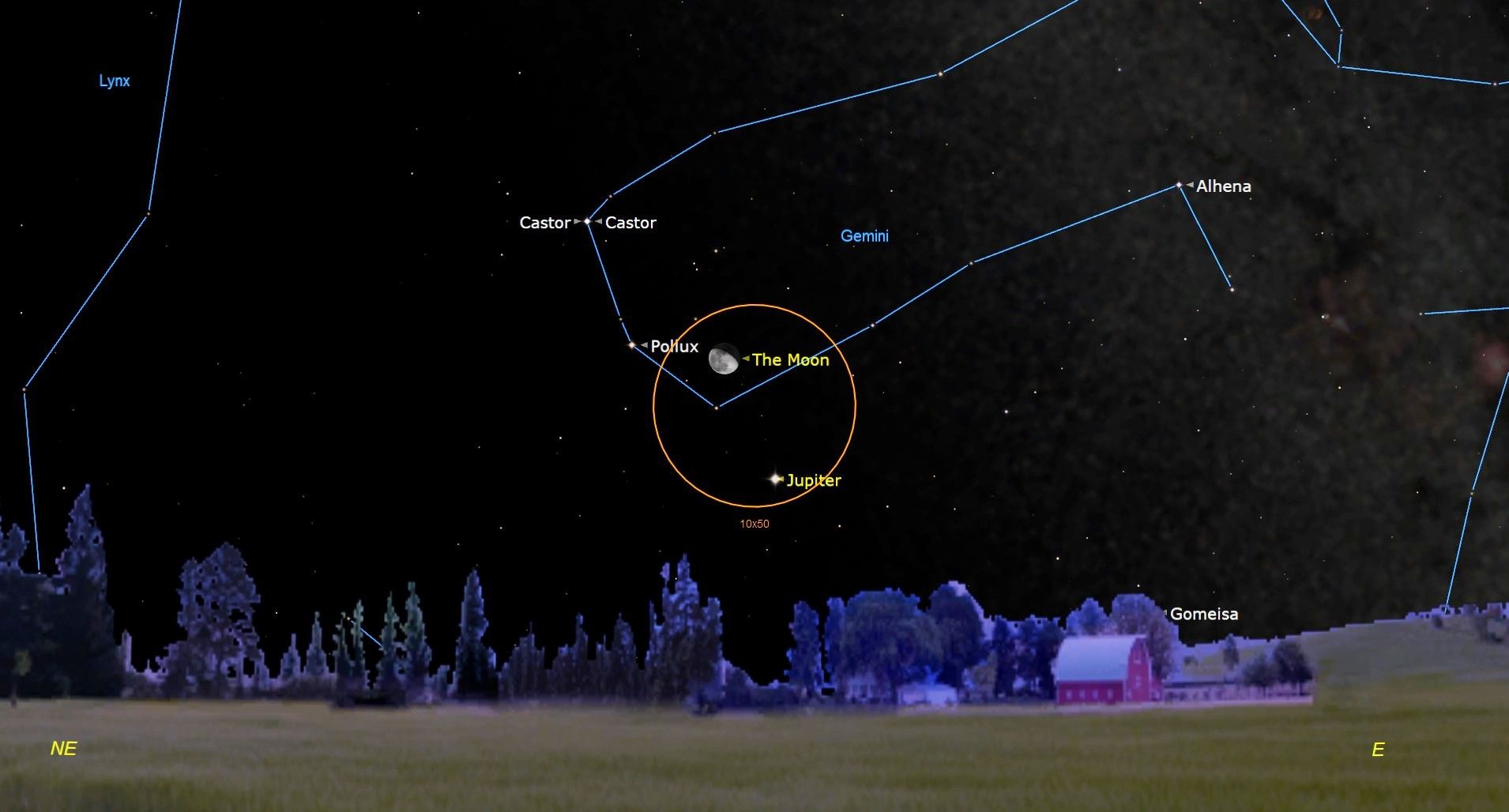

At around 10:00 p.m. local time on Sunday (Nov. 9), if you look low toward the east-northeast sky, you will see a waning gibbous moon, 72 percent illuminated, and shining prominently below it will be a brilliant, silvery non-twinkling “star.” But in reality, that star is not a star at all, but the largest planet in our solar system: the planet Jupiter. The distance between the moon and Jupiter will be about 4.5 degrees. Your clenched fist held at arm’s length is equal to approximately 10 degrees. So, the gap separating this celestial pair will appear to be equal to roughly half a fist.

Jupiter is currently situated against the stars of Gemini the Twins where the ecliptic — the apparent path of the sun, moon and planets — comes farthest north, at +23 degrees declination. This is fortunate for Northern Hemisphere observers, since the farther north a planet is, the more time it will spend above the horizon and the higher it will stand above the southern horizon at the midpoint of its path across the sky. For those living in the southern U.S., when Jupiter crosses the meridian in the early morning hours, it is not far from the point directly overhead (the zenith).

When worlds (and a star) align

Because the moon appears to move to the east (left) against the background stars at roughly its own apparent diameter each hour, its position relative to Jupiter and Pollux will change noticeably during the course of the night.

The time when all three objects are more-or-less aligned along a straight line; when the moon appears to sit directly between Pollux and Jupiter, will differ depending on where you are located.

Those in the Eastern time zone will see this happen within a few minutes of 1:45 a.m.

For those living within the Central time zone, this will happen at around 12:25 a.m.

In the Mountain time zone the line-up comes at approximately 11:20 p.m. and for those in the Pacific time zone, only shortly after the moon, star and planet have risen: around 10 p.m., very low above the east-northeast horizon.

If you cast a gaze toward the moon as dawn breaks on Monday morning, note how much the configuration has changed; the moon has moved well off to the east leaving Jupiter and Pollux behind.

Telescopic treat

Jupiter is currently the best observer’s planet and will remain so all winter and into next spring. But sharp telescopic views are seldom possible until it is about 30 degrees above the horizon, given the typical turbulent state of Earth’s atmosphere. You’ll have to wait until midnight for Jupiter to reach 30 degrees altitude, which to some is the psychological dividing line between objects that are “low” and “well placed.” Half the area of the hemispherical sky dome is below 30 degrees altitude (or “three fists”).

If you do check out Jupiter with a small telescope on Sunday night, you’ll see all four Galilean moons, with Ganymede and Io on one side of Jupiter and Europa and Callisto on the other. The ever-changing positions of the satellites relative to each other are always fun to watch.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky and Telescope and other publications.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly