Now Reading: Dying old stars destroy their planets, new research shows

-

01

Dying old stars destroy their planets, new research shows

Dying old stars destroy their planets, new research shows

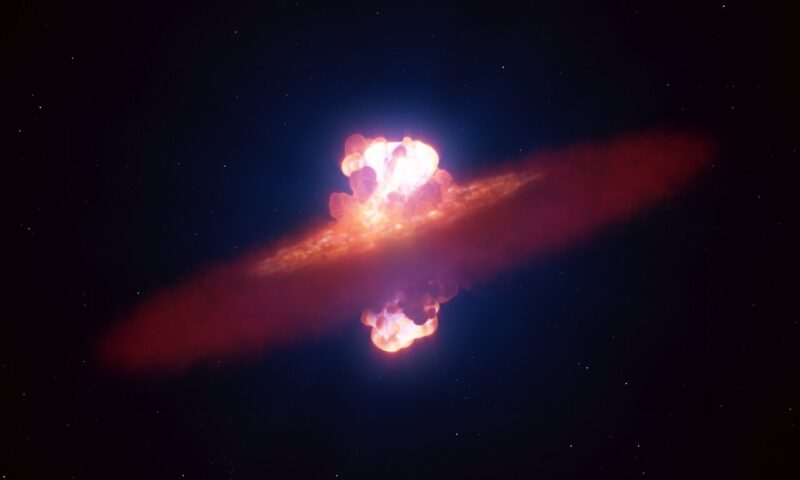

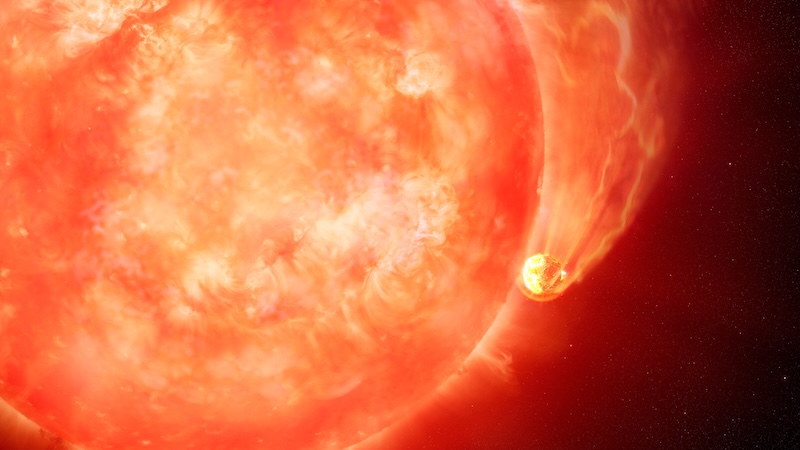

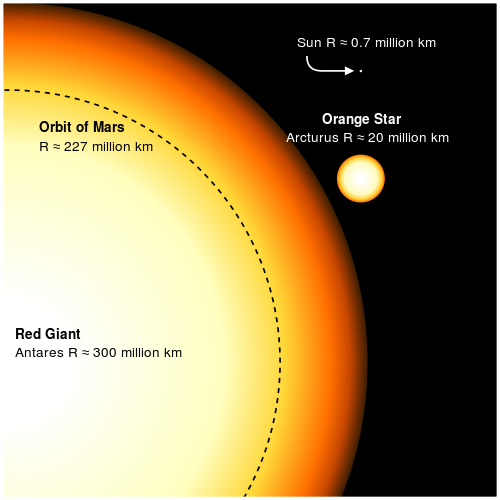

- Red giant stars are dying stars that were once like the sun and have now swollen enormously as they enter the latter stages of their lives. Can their planets survive?

- Red giants will consume and destroy any planets that are too close, astronomers have long suspected. New evidence supports that scenario.

- Planets are much less common around red giants – especially older red giants – the new research also shows. This suggests that most of their planets have already been destroyed.

Old stars destroy their planets

Do old stars destroy the planets closest to them? Scientists have long known that stars like the sun eventually expand into red giants as they begin to die. It’s been assumed that any exoplanets close enough to the original star would be consumed. On November 5, 2025, researchers at University College London and the University of Warwick in the U.K. presented more evidence to show that’s the case. They studied nearly half a million red giant stars. And they determined that exoplanets were much less likely to be found around the red giants, especially older red giants, than around other stars. This suggests that many planets – the closest ones in particular – might have already been destroyed.

Using data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), the researchers identified 130 planets and planetary candidates. Of those, 33 were new and previously unknown.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed findings in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society on October 15, 2025.

Observations indicate that giant planets orbiting close to aging stars are less common around red giants, suggesting many may be destroyed as their host stars expand and evolve.

— Science X / Phys.org (@sciencex.bsky.social) 2025-11-05T12:00:19-05:00

Spiraling to destruction

The scenario is fairly simple. As the star swells into a red giant, planets that are too close will start to spiral inward due to the powerful gravitational pull. Ultimately, the bloated giant star consumes them. Lead author Edward Bryant at Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London and the University of Warwick in the U.K. explained:

This is strong evidence that as stars evolve off their main sequence, they can quickly cause planets to spiral into them and be destroyed. This has been the subject of debate and theory for some time, but now we can see the impact of this directly and measure it at the level of a large population of stars.

We expected to see this effect, but we were still surprised by just how efficient these stars seem to be at engulfing their close planets.

We think the destruction happens because of the gravitational tug-of-war between the planet and the star, called tidal interaction. As the star evolves and expands, this interaction becomes stronger.

Just like the moon pulls on Earth’s oceans to create tides, the planet pulls on the star. These interactions slow the planet down and cause its orbit to shrink, making it spiral inward until it either breaks apart or falls into the star.

130 planets and planetary candidates

Overall, the research team studied 130 exoplanets and planetary candidates (planets that are tentatively identified but need to be confirmed) in the TESS data.

Initially, the researchers started with 15,000 possible planetary signals. Then, after eliminating false positives, they reduced the number to 130. And 33 of those were brand-new candidates not known before. In addition, astronomers already knew of 48 of the planets, and 49 that scientists had already identified as planetary candidates.

Fewer planets for older red giant stars

Notably, the researchers found that the older the star – in the late red giant stage – the fewer planets it had. Stars that have aged enough to become red giants are post-main sequence stars. Stars that haven’t reached that stage yet, like our own sun, are main sequence stars.

Likewise, there was also a noticeable pattern with the age of the stars within the post-main sequence stage. The overall occurrence rate of planets was 0.28%. The “youngest” ones – stars that had just become red giants – had planets at a rate 0f 0.35%. But, as the red giant stars themselves continued to get older, that rate dropped to 0.11%.

This supports the scenario that as red giants continue to age and expand, they engulf more of their planets. The researchers still want to understand better just how the planets begin to spiral inward to their stars. To do so, astronomers need to know their masses, which they can find using the TESS data. As Bryant noted:

Once we have these planets’ masses, that will help us understand exactly what is causing these planets to spiral in and be destroyed.

The findings also foreshadow the fate of our own solar system. Indeed, our own sun faces the same fate. Will any of the planets survive? Luckily for us, it’s still several billion years in the future!

Bottom line: Astronomers have found new evidence that dying stars destroy their planets – with the closest planets at greatest risk – as the stars swell up into red giants.

Via Royal Astronomical Society

Read more: Phoenix exoplanet’s puffy atmosphere survives red giant star

Read more: An all-sky red giant star symphony

The post Dying old stars destroy their planets, new research shows first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly