Now Reading: ESA and NASA deliver first joint picture of Greenland Ice Sheet melting

-

01

ESA and NASA deliver first joint picture of Greenland Ice Sheet melting

ESA and NASA deliver first joint picture of Greenland Ice Sheet melting

20/12/2024

15284 views

44 likes

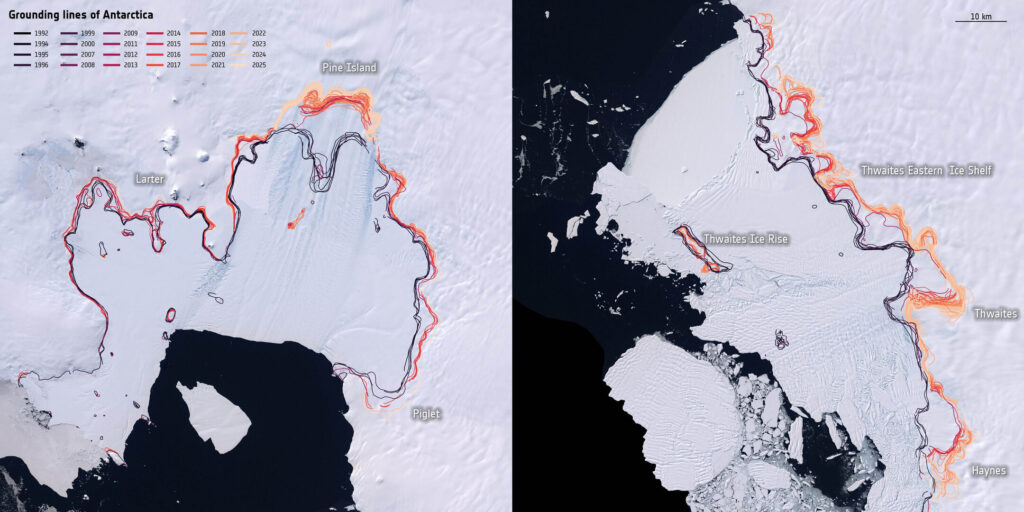

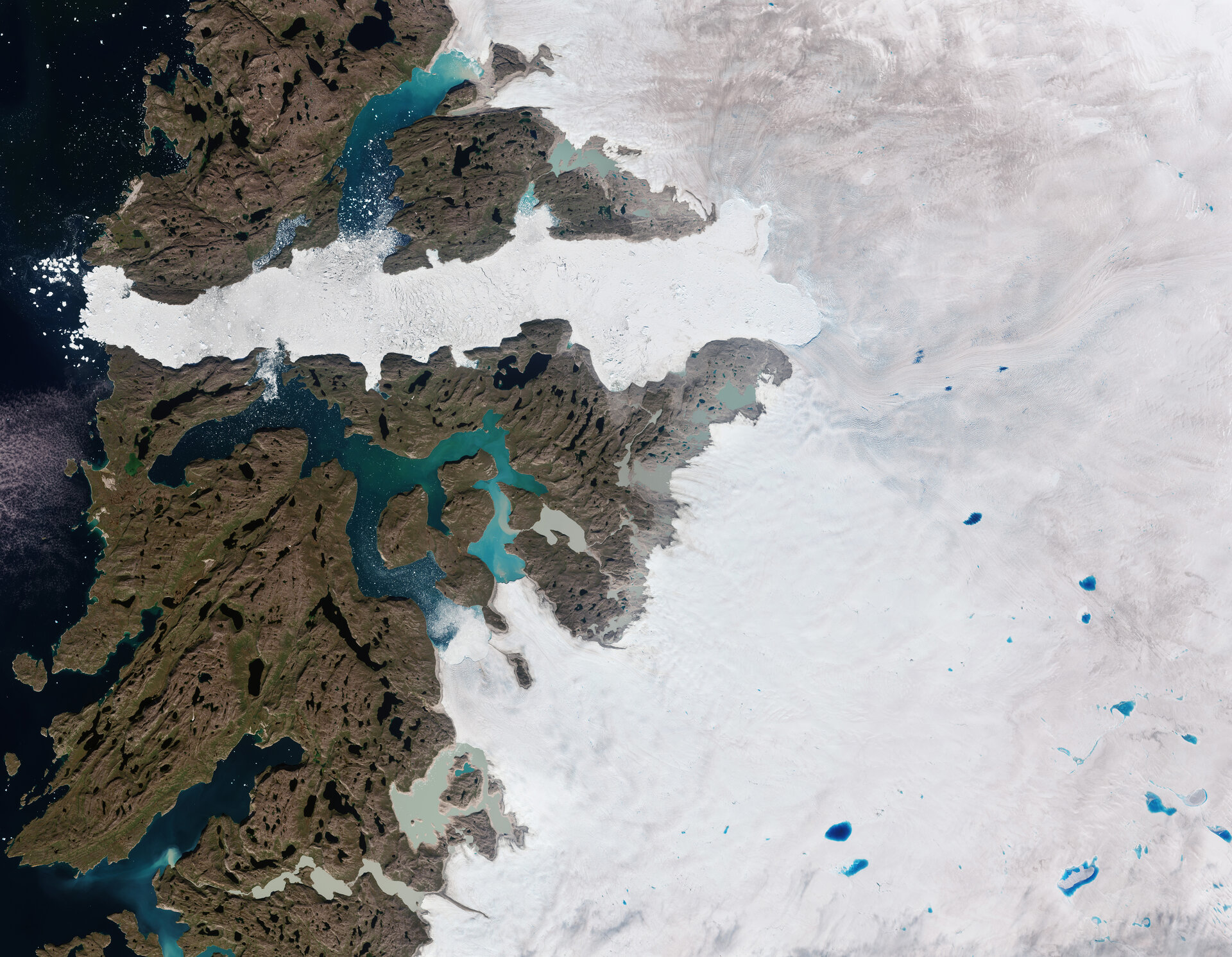

Global warming is driving the rapid melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet, contributing to global sea level rise and disrupting weather patterns worldwide. Because of this, precise measurements of its changing shape are of critical importance for adapting to climate change.

Now, scientists have delivered the first measurements of the Greenland Ice Sheet’s changing shape using data from ESA’s CryoSat and NASA’s ICESat-2 ice missions.

Although both satellites carry altimeters as their primary sensor, they make use of different technologies to collect their measurements. CryoSat uses a radar system to determine Earth’s surface height, while ICESat-2 uses a laser system for the same task.

Although radar signals can pass through clouds, they also penetrate the ice sheet surface and have to be adjusted to compensate for this effect. Laser signals, on the other hand, reflect from the actual surface but cannot record when clouds are present. The missions are therefore highly complementary, and combining their measurements has been a holy grail for polar science.

A new study from scientists at the UK Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM) and published today in Geophysical Research Letters, shows that CryoSat and ICESat-2 measurements of Greenland Ice Sheet elevation change agree to within 3% of the changes taking place.

This confirms that both satellites can be combined to produce a more reliable estimate of ice loss than either could achieve alone. It also means that if one mission were to fail, the other could be relied upon to maintain our record of polar ice change.

Between 2010 and 2023, the Greenland Ice Sheet thinned by 1.2 m on average. However, much larger changes occurred across the ice sheet’s ablation zone where summer melting exceeds winter snowfall; there, the average thinning amounted to 6.4 m.

The most extreme thinning occurred at the ice sheets outlet glaciers. At Sermeq Kujalleq in west central Greenland (also known as Jakobshavn Isbræ), the peak thinning was 67 m, and Zachariae Isstrøm in the northeast the peak thinning was 75 m.

Altogether, the ice sheet shrank by 2347 cubic kilometres across the 13-year survey period – similar to the amount of water stored in Africa’s Lake Victoria. The biggest changes occurred in 2012 and 2019, when the ice sheet shrank by more than 400 cubic kilometres because of extreme melting in those years.

Greenland’s ice melting also has profound effects on global ocean circulation and weather patterns. These changes have far-reaching impacts on ecosystems and communities worldwide. The availability of accurate, up-to-date data on ice sheet changes will be critical in helping us to prepare for and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

“We are very excited to have discovered that CryoSat and ICESat-2 are in such close agreement,” says lead author and CPOM researcher Nitin Ravinder. “Their complementary nature provides a strong motivation to combine the data sets to produce improved estimates of ice sheet volume and mass changes. As ice sheet mass loss is a key contributor to global sea level rise, this is incredibly useful for the scientific community and policymakers.”

The study made use of four years of measurements from both missions, including those collected during the Cryo2ice campaign, a pioneering ESA-NASA partnership initiated in 2020. By adjusting CryoSat’s orbit to synchronise with ICESat-2, ESA enabled the near-simultaneous collection of radar and laser data over the same regions.

This alignment allows scientists to measure snow depth from space, offering unprecedented accuracy in tracking sea and land ice thickness.

Tommaso Parrinello, CryoSat Mission Manager at ESA, expressed optimism about the campaign’s impact: “CryoSat has provided an invaluable platform for understanding our planet’s ice coverage over the past 14 years, but by aligning our data with ICESat-2, we’ve opened new avenues for precision and insight.

“This collaboration represents an exciting step forward, not just in terms of technology but in how we can better serve scientists and policymakers who rely on our data to understand and mitigate climate impacts.”

“It is great to see that the data from ‘sister missions’ are providing a consistent picture of the changes going on in Greenland,” says Thorsten Markus, project scientist for the ICESat-2 mission at NASA.

“Understanding the similarities and differences between radar and lidar ice sheet height measurements allow us to fully exploit the complementary nature of those satellite missions. Studies like this are critical to put a comprehensive time series of the ICESat, CryoSat-2, ICESat-2, and, in the future, CRISTAL missions together.”

ESA’s CryoSat continues to be instrumental in our understanding of climate related changes in polar ice, working alongside NASA’s ICESat-2 to provide robust, accurate data on ice sheet changes. Together, these missions represent a significant step forward in monitoring polar ice loss and preparing for its global consequences.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly