Now Reading: First sea-level records for coastal community protection

-

01

First sea-level records for coastal community protection

First sea-level records for coastal community protection

25/06/2025

333 views

6 likes

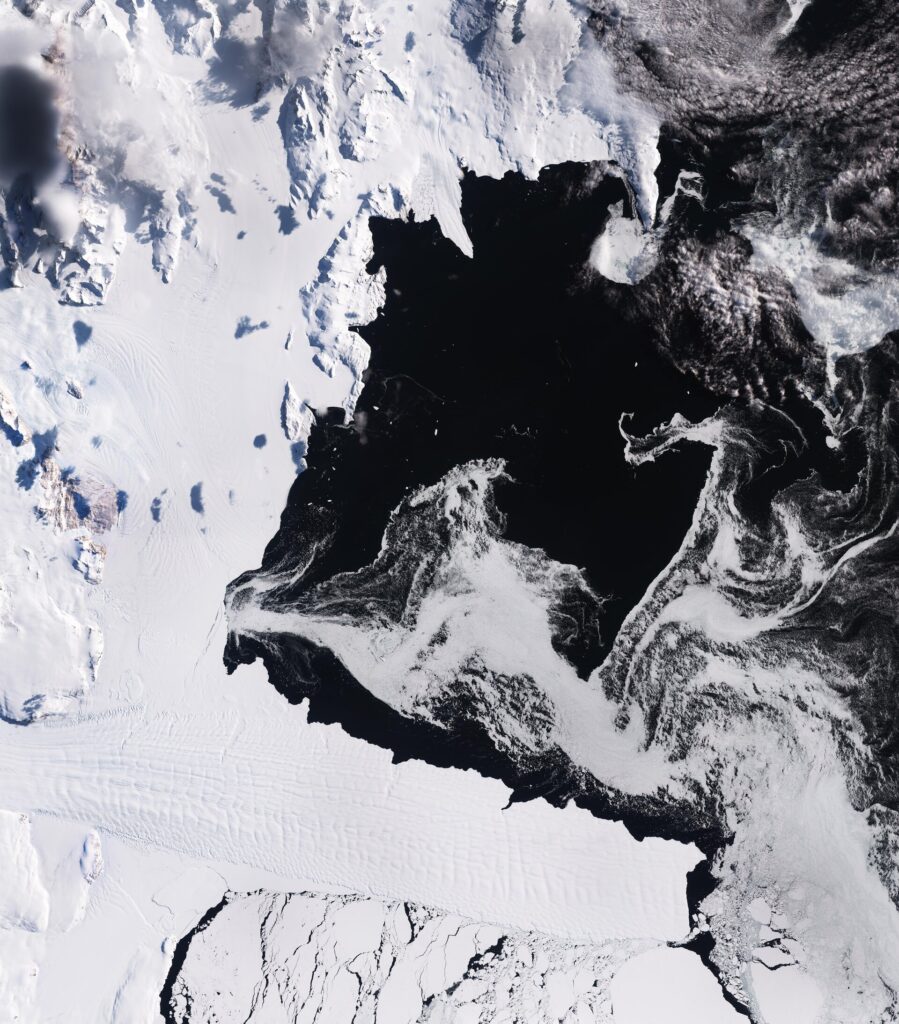

While satellites have revolutionised our ability to measure sea level with remarkable precision, their data becomes less reliable near coasts – where accurate information is most urgently needed. To address this critical gap, ESA’s Climate Change Initiative Sea Level Project research team has reprocessed almost two decades of satellite data to establish a pioneering network of ‘virtual’ coastal stations. These stations now provide, for the first time, reliable and consistent sea-level measurements along coastlines.

Long-term satellite observations reveal that global sea levels are not only rising, but doing so at an accelerating rate. Since 1993, the global mean sea level has been increasing at average of over 3 mm a year – but over the last 10 years, this rate has exceeded 4 mm per year.

Our ability to monitor sea-level rise is thanks largely to the long-term record of sea-surface height from satellite radar altimeters, initially provided by the French–US Topex Poseidon satellite and the Jason series of satellites, and now by the Copernicus Sentinel-6 mission.

As remarkable as this record is, data from satellite radar altimeters are not quite as accurate when they measure within 20 km of coastlines compared to the open ocean. This is because the presence of land interferes with the satellite’s radar signal.

ESA’s Climate Change Initiative Sea Level Project, with the scientific leadership of Anny Cazenave from France’s Laboratory of Space Geophysical and Oceanographic Studies and one of the pioneers of satellite altimetry, has now overcome the decades-long coastal measurement challenge by revisiting and reprocessing sea-level records from satellite radar altimeters spanning 2002 to 2021 to create a network of 1647 ‘virtual’ coastal stations.

Presented at ESA’s Living Planet Symposium this week, these virtual stations provide accurate data on coastal sea levels for the first time, including areas where no systematic long-term measurements were previously available. This is particularly valuable for remote coastal areas where tide gauges are often lacking or limited, closing a critical data gap in climate science.

The new dataset will help scientists and policymakers to understand and predict the impact of rising sea levels on coastal areas and to develop effective coastal protection measures that safeguard people, ecosystems and economies.

Jean-François Legeais, coordinator of the Sea Level Project, explained, “This breakthrough is a paradigm shift for climate research and coastal adaptation. In Asia alone, 310 million people could be affected by rising sea levels by 2060, which highlights the need for reliable data.

“Until now, this has required tidal gauges, which are not installed in all regions worldwide. However, we now have two decades of consistent global coastal records, including from regions that have never been monitored before.”

Initial scientific analyses using the new data product are already yielding insightful results. For instance, the research team has identified a significant acceleration in the rise of the coastal sea level in the Gulf of Mexico since the early 2010s.

They have also found that natural climate phenomena such as El Niño are the main drivers of multiyear sea-level fluctuations, with responses varying greatly from region to region.

Climate change is undoubtedly the leading driver of sea-level rise. Approximately 45% of this rise is a result of melting of ice from the Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets, as well as from mountain glaciers. Another major contributor, accounting for about one-third of sea-level rise, is because of thermal expansion, where warming seawater increases in volume.

Sea-level rise is arguably one of the most serious consequences of the climate crisis. Currently, more than 680 million people – nearly 10% of the global population – live in low-lying coastal areas directly threatened by floods.

For every additional centimetre of sea-level rise, an extra three million people are at risk of annual flooding.

Against this backdrop, the Sea Level Project focuses on three critical research areas: investigating whether sea levels rise uniformly along coastlines compared to open waters, improving the accuracy of coastal sea-level measurements, and examining the natural and human factors influencing long-term coastal sea level variations.

Precise data for resilient coasts

The new dataset enables climate researchers to carry out precise trend analyses of specific coastal areas over the two-decade period, as well as investigating the relationship between sea-level variations and global climate phenomena.

Also, correlations between river flow and sea-level rise can be analysed to understand how freshwater discharge affects regional coastal dynamics and contributes to local variations in sea-level trends.

For policymakers, coastal protection planners and urban developers, the dataset provides important information for assessing risks and for the planning and design of future flood protection systems.

Additionally, the product can be used to compare and improve climate models, which help anticipate future changes and inform long-term planning. It closes critical data gaps in regions without tide gauges, and supports the development of localised climate adaptation strategies, from infrastructure planning to the continuous monitoring of coastal changes worldwide.

Enhancing coastal protection and planning

Enhanced versions of the product are under development that will account for vertical land shifts – known as subsidence. Previous studies, using ESA’s satellite records, reveal that subsidence can quadruple the rate of relative coastal sea level compared to the global average, including some of the world’s most populous cities.

They will draw on precision satellite instruments, including Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) and Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), which are essential for accurately measuring these land movements.

To demonstrate this, the team is currently conducting initial trials using InSAR-based data from the Copernicus Land Monitoring Service along European coastlines.

Prof. Cazenave said, “For people living in coastal areas, it is the relative sea level that really matters. The actual flood risk comes from how the sea level changes in relation to the land surface. If the land is sinking while the sea level is rising, the combined effect greatly increases the danger.

The Sea Level Project’s work highlights the importance of long-term, high-quality data in addressing the specific challenges of climate change. ESA’s Sarah Connors, commented, “The Climate Change Initiative provides policymakers and planners with the tools they need to protect coastal regions and strengthen resilience to sea level rise, among other things.

“By providing detailed insights into sea-level changes along coastlines, we are making a direct contribution to one of the key commitments of the 2015 Paris Agreement: helping vulnerable communities adapt to the impacts of climate change.”

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly