Now Reading: Gaia proves our skies are filled with chains of starry gatherings

-

01

Gaia proves our skies are filled with chains of starry gatherings

Gaia proves our skies are filled with chains of starry gatherings

26/08/2025

576 views

14 likes

In the past decade, the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission has revealed the nature, history, and behaviour of billions of stars. Our pioneering stargazer has reshaped our view of the skies around us like no other, revealing that star clusters are more connected than expected over vast distances.

Understanding the Milky Way and its stars is what Gaia was built for – and the telescope was certainly fit for the job.

After more than a decade spent observing our skies, Gaia is now enjoying a quiet retirement, with most of its data is yet to be released. However, the mission’s first data releases have already nailed down the locations, motions, and brightnesses of stars in our galaxy with truly unprecedented precision, allowing us to understand these Milky Way residents like never before.

Since it opened its eyes in 2014, Gaia has mapped how different stars zip through space and pinpointed their whereabouts more precisely than ever. The telescope has watched whether they shrink and swell, spotted surprising ‘starquakes’, monitored how stars grow, evolve, and crystallise as they die, and discovered stellar travellers seeking solace in our galaxy after being kicked out of their own. It has created the largest and most precise multi-dimensional map of our galaxy ever.

Crucially, Gaia has meticulously scanned the contents of our galaxy to understand star clusters.

There are two types of cluster. The first are open clusters: small gatherings of hundreds or thousands of stars typically found closer to the main disc of a galaxy. The second are globular clusters, which lurk at a galaxy’s outer edges or central regions and can contain millions of starry residents.

While most stars are born and grow up together in clusters, star families don’t stick together forever; over time, stars disperse into the broader population of stars in the Milky Way. In this way, star clusters define the nature and composition of our galaxy’s disc and hold clues to what happened in its past. If we’re to understand the history and evolution of the Milky Way, we need to understand star clusters.

So – what has Gaia told us about them?

Redefining star clusters: a cosmic census

Gaia has collected trillions of observations of billions of stars, producing unprecedentedly precise data catalogues filled with information about star motions, ages, locations, and more. This colossal amount of data – not even one-third of which has been released so far – is a truly unique strength of Gaia. When working with cosmic objects as numerous as stars, exploring them in batch offers new insights that we simply can’t get when looking at them in smaller numbers.

The spacecraft has performed a cluster ‘census’, mapping cluster locations, defining their main characteristics (age, size, distance, composition, internal and external motions and more) and distinguishing real star clusters from chance alignments on the sky (asterisms). To do so, Gaia closely monitors the stars thought to be members of a given cluster, watching whether they all move in the same way, and using precise photometry (measuring the light streaming off a star) to figure out if they’re of the same age and at the same distance from us.

“Thanks to Gaia, we can find and remove rogue stars that don’t actually belong to a cluster, making all of our science far more accurate,” says Antonella Vallenari of Padova Astronomical Observatory (INAF), Italy, and Deputy Chair of the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC).

“We can also find an incredible numbers of new clusters. Gaia can spot and group stars that are born together and moving similarly, even if they’re spread out through space. We’ve used Gaia to find new open clusters ranging from the very small – just a few pairs of co-moving stars! – all the way up those a few thousands strong.”

Gaia’s high-precision data has allowed us to find new coherent groups of stars – those moving in the same way, or in the same region of space – and locate complex structures hidden within known clusters. Scientists have also applied Artificial Intelligence (AI) to Gaia data, using algorithms and machine learning approaches to pinpoint new cluster members and subgroups of stars.

In this way, Gaia has pushed us to rethink how we hunt for stellar groups. It’s discovered that some star families behave oddly, without the kind of coherent movement that we might expect to see from stars that formed together. Gaia recently revealed an unusual family of stars all strangely eager to leave home, rushing out into the Milky Way in a haphazard, uncoordinated way. If looking only for stars moving similarly, this family would have slipped through our net, but Gaia’s huge, high-quality datasets enabled scientists to use new models that were able to spot them.

Closer to home: mapping the Sun’s neighbourhood

Gaia has revolutionised our view of the solar neighbourhood, allowing scientists to comprehensively map all the stars and interstellar ‘stuff’ near the Sun in a way they were unable to do before.

Gaia’s sky maps in both 3D and 6D – in all three spatial coordinates (3D) plus three velocities (moving towards and away from us, and across the sky) – have revealed the precise motions and positions of millions of nearby stars.

The maps have also revealed the structure of dark molecular clouds; numerous young clusters, star associations, and stellar streams in the space close to us; and nascent stars (including ‘Young Stellar Objects’) emerging from their birth clouds. With Gaia, astronomers have been able to map the nurseries where Young Stellar Objects spring to life in 3D space, revealing the true structure and extent of two of the closest star associations to us: Orion OB1 and Scorpius–Centaurus.

Scientists have also used Gaia to explore diffuse ‘coronas’ of stars around clusters, tidal tails (more on this later), and cluster families, tracing how stars form near the Sun. It turns out that many young clusters aren’t isolated – they’re part of larger cluster ‘chains’ or ‘families’, sharing common origins and star formation histories.

Overall, Gaia has redefined star formation in our patch of space. We now know a lot more about how this process is influenced and driven by the existing stars within a birth cloud, something known as stellar feedback. Stars throw energy and mass out into space via radiation, winds, explosions, jets, and more. Feedback is crucial in redistributing chemical elements, gas, and dust throughout space – and it helps regulate star formation, something Gaia has explored by mapping star associations and tracing the motion of young stars.

Notably, Gaia has found that small aggregates of young stars like Orion OB1, named OB associations, are in fact born that way, rather than being old, expanded clusters, as we thought.

Interconnected: Tracing the ‘stuff’ and spirals of the Milky Way

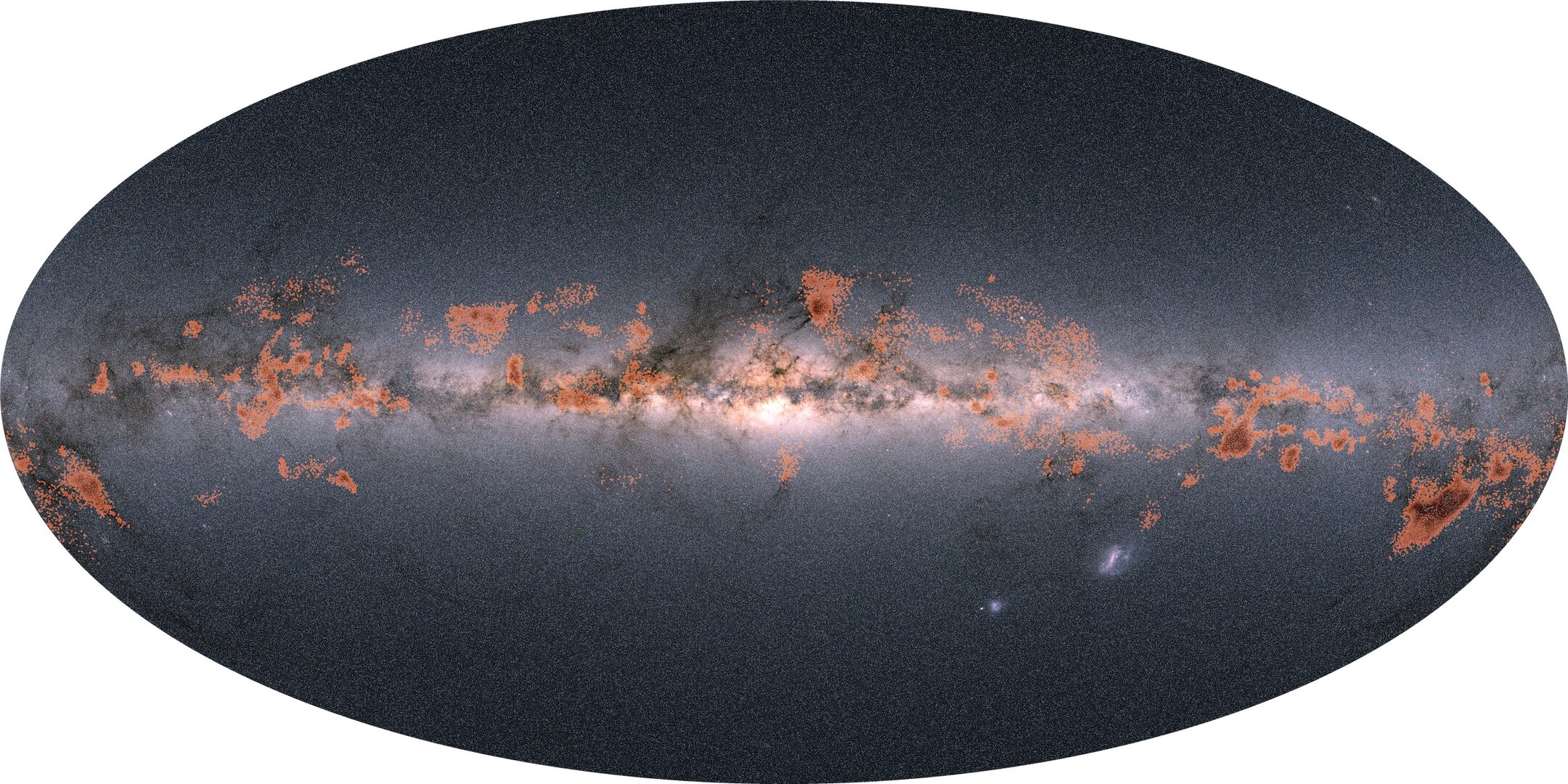

Since Gaia, it’s become clear that star-forming regions, clusters, and associations are interconnected on truly vast scales. It is fundamentally reframing our understanding of how gas and stars populate the skies we see, and how star formation is driven throughout the Milky Way.

The telescope has redefined a nearby ring of stars known as the Gould Belt, finding it to be a trick of the eye, with its stars instead aligned along two prominent linear structures (a gas spur extending from the Scorpius-Centaurus association known as the Split, and the Radcliffe Wave, a long, undulating string of gas that connects regions such as Orion, Perseus and Taurus and contains the mass of 3 million stars). It’s also mapped the 3D structure of superbubbles, shells, and spurs, all of which are blown and shaped by the winds of stars and supernovas within.

Building on this new view of interconnected skies, astronomers have used Gaia to better understand the spiral structure of our galaxy and the thickness of its disc. Gaia observations show that young clusters seem to move at different speeds and in slightly different ways depending on their location within the Milky Way’s spiral arms. Star clusters are unevenly distributed through the arms, implying that these huge whirling structures are likely transient, not long-lived, in nature.

Gaia has also revealed that large-scale galactic dynamics influence how young star clusters form in the first place, and how they eventually dissolve. In fact, Gaia has revealed quite a bit about young clusters, mapping the dark clouds and dusty regions in which they form. This formation appears to be surprisingly sub-structured and messy. Gaia has shown that structures resembling streams, beads, strings, pearls, snakes, rings, or filaments of stars are reasonably common in young cluster formation, with these arrangements remaining visible for millions of years throughout the Milky Way.

The slow goodbye: Unravelling tidal tails

As clusters move through the Milky Way, they’re disturbed by different clumps and structures of matter, from molecular clouds to dark matter and to the ‘bar’ of stars cutting through our galaxy’s centre. These interactions tug at the clusters and stretch them apart, creating long ‘tidal’ tails of stars and gas.

“Tidal tails aren’t just remnants of a cluster’s past: they’re powerful dynamical tracers that tell the tale of a cluster’s lifetime and place in the galaxy,” says Tereza Jeřábková of Masaryk University, the Czech Republic, an expert in star formation and regular user of Gaia data. “Historically we’d only seen these tails around clusters in sparser areas of the Milky Way, as they stand out better against emptier skies. It was far harder to spot them in our galaxy’s densest regions – but Gaia changed all that.”

Thanks to Gaia’s high-precision astrometry, scientists have been able to spot extended tails around the Hyades cluster and traced the kinematics of tails around the Coma Berenices cluster. Gaia has also dug into the properties of the tails themselves, finding them to frequently be asymmetric in density and length. It turns out that these tidal tails can be enormous, stretching over many thousands of light-years. The Hyades cluster, for example, though seemingly modest in size, has tidal tails that span huge sections of the sky – a silent testimony to the cluster’s origin, evolution, and ongoing dissolution into the galaxy.

“The field is evolving rapidly, and has made progress even since we discovered the Hyades tails,” adds Tereza. “Researchers are now using Gaia-based methods to uncover tidal features in other nearby open clusters, such as Coma Berenices, Blanco 1, NGC 752, Praesepe, and more.”

Importantly, Gaia has pinpointed stars that have escaped their birthplace. This is important to understand more about clusters, their residents, and to identify more recent tidal features. It has also been instrumental in confirming that the stars within tidal tails are genuine escapees from the cluster itself, and not a chance alignment or stars that just happened to be in the area. Astronomers achieved this by taking tidal tail star candidates from Gaia data and looking at how they spin on their axes.

Thanks to Gaia, open clusters are no longer seen as isolated entities but as dynamically evolving structures, slowly dissolving into our galaxy and leaving traces of their past lives behind. “Current efforts are focused on detecting more tidal tails, pushing to larger extents and fainter limits, and refining what we know of the constituent stars,” adds Tereza. “As data improves and new methods emerge, our ability to reconstruct the past lives of clusters will only continue to grow.”

Upcoming sky surveys – including 4MOST and WEAVE – and missions such as ESA’s Plato – ESA’s forthcoming planet-hunter that will also characterise rocky exoplanets and their host stars – will complement Gaia’s findings by revealing more about the stars in our skies, enabling us to study features such as tidal tails in greater detail.

A stellar revolution

ESA’s Gaia mission is delivering new and updated science at pace, supplying astronomers with the high-volume, large-scale data they need to dig deeper into our skies.

“Gaia’s datasets are significantly more detailed and precise than any that have come before. It’s no exaggeration to say that the mission has brought about a revolution in Milky Way astronomy, especially when it comes to star clusters,” says Johannes Sahlmann, ESA Project Scientist for Gaia.

“Excitingly, Gaia has revealed that, rather than clusters being solitary in nature, our skies are filled with chains of these starry gatherings. The cosmos is marbled with vast threads and strings that link cluster to cluster and tie stars together in ways we didn’t expect.”

Gaia has now completed its sky-scanning observations and, as of March 2025, is quietly orbiting the Sun in its retirement orbit. The vast majority of data collected by the spacecraft is yet to be released, with a couple of huge data releases planned by the end of the decade (Data Release 4, based on 5.5 years of Gaia observations, is expected in December 2026, and Data Release 5, based on all 10.5 years, is expected not before the end of 2030). However, scientists are already using Gaia’s treasure trove of released observations – gathered in its first three years of observing – to explore billions of stars and objects in our galaxy and beyond.

“Gaia’s spacecraft operations may have ended, but its contributions to science are in full swing,” adds Johannes. “It’s a really exciting time for stellar scientists. As more data are released to the scientific community in coming years we’ll see another flurry of discoveries, further reshaping what we know about our skies in a truly transformative way.”

Notes for editors:

More in-depth information is available here: https://www.cosmos.esa.int/en/web/gaia/milky-way

Related stories:

Gaia data is freely available via ESA’s Gaia archive: https://gea.esac.esa.int/archive/

More information on Gaia’s upcoming data releases can be found here: https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/gaia/release

For more information, please contact:

ESA Media relations

media@esa.int

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors