Now Reading: House committee advances NASA authorization bill

-

01

House committee advances NASA authorization bill

House committee advances NASA authorization bill

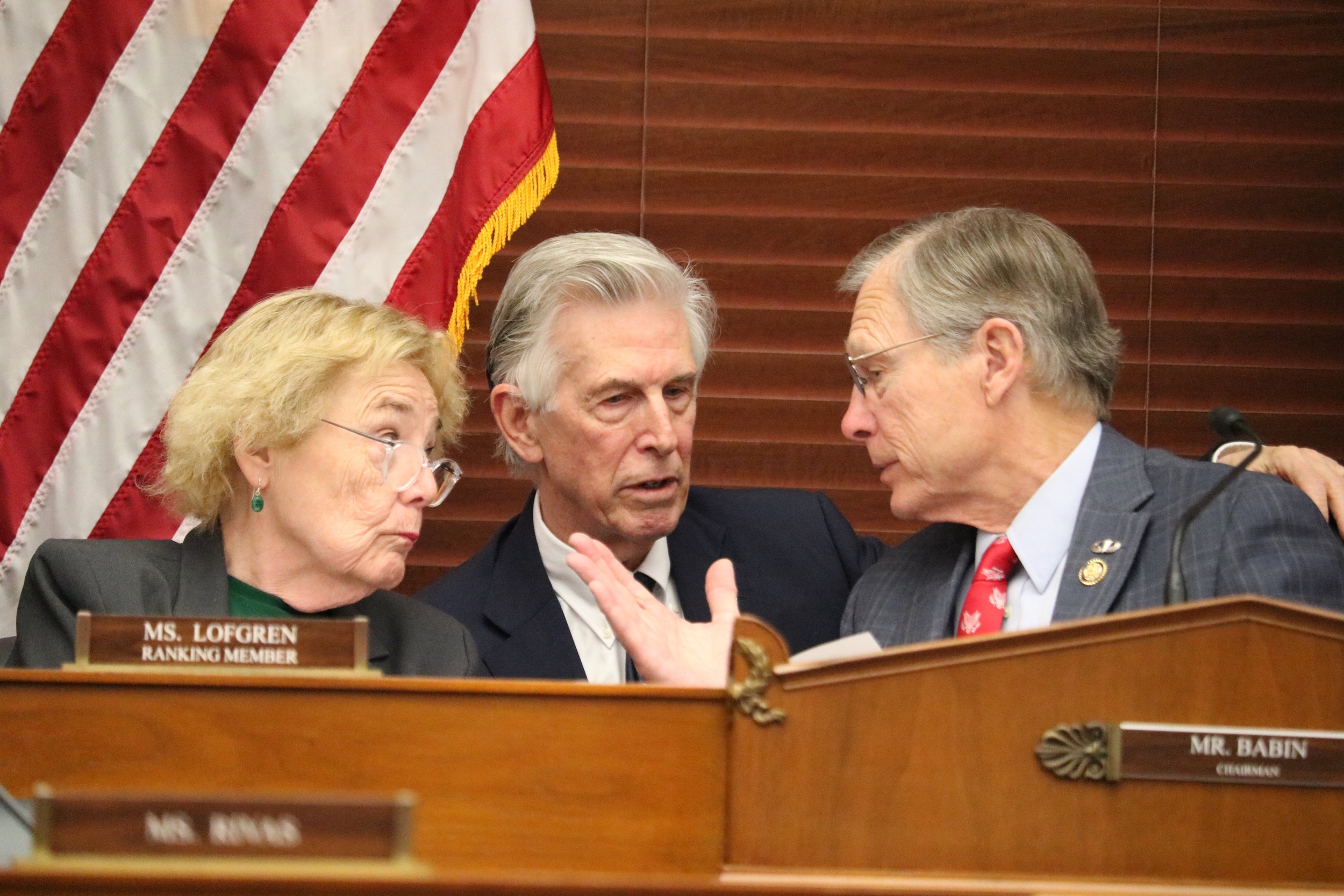

WASHINGTON — The House Science Committee unanimously approved a NASA authorization bill Feb. 4 after adopting dozens of amendments.

The committee voted 37-0 to favorably report the NASA Reauthorization Act of 2026, sending it to the full House for consideration. The bipartisan leadership of the committee and its space subcommittee introduced the bill last week.

The legislation largely reaffirms existing NASA programs and policies. It also directs the agency to produce a wide range of reports, including increased scrutiny of commercial lunar lander development for the Artemis lunar exploration campaign and of spacesuits for use on Artemis missions and the International Space Station.

The bill’s sponsors said the measure is intended to ensure NASA remains focused amid rising geopolitical competition.

“With China nipping at our heels and investing heavily in its own ambitions beyond Earth, we cannot afford to drift without direction,” said Rep. Brian Babin, R-Texas, chairman of the committee. “This legislation ensures the United States sets the pace, establishes the standards and carries forward the spirit of exploration that has long defined our nation.”

“Our space primacy is not assured, and we cannot stay ahead of our competitors in the Chinese Communist Party without a robust, well-funded agency that follows a clear, consistent vision powered by an unmatched workforce,” said Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif., the committee’s ranking member.

During the markup session, which lasted more than three hours, the committee adopted more than 40 amendments, all by voice vote. The amendments spanned the breadth of NASA’s activities, from exploration and science to aeronautics and education.

Many amendments directed NASA to produce reports on specific topics or reaffirmed existing programs and policies. One amendment, offered by Rep. Keith Self, R-Texas, would codify the goal of establishing the “initial elements” of a lunar outpost by 2030, a target included in a December executive order on space policy by President Trump.

Several amendments focused on expanding commercial uses of space. One would formally authorize NASA to purchase commercial services for deep-space cargo and crew transportation but does not provide additional guidance on how the agency should do so. Another calls on NASA to establish a Commercial Microgravity Research Payload Services program to give researchers access to platforms beyond the ISS for microgravity research.

A third amendment would formally endorse “the fullest commercial use of space,” including “facilitating the expansion of United States private sector use of and the growing and enduring presence of private citizens in Earth orbit, in cislunar space, on the surface of the Moon, and beyond.”

That amendment drew praise from commercial space advocates, including the Space Frontier Foundation. “Congress is clearly stating that private human presence and economic activity beyond Earth are not only encouraged but essential and expected outcomes of U.S. space policy,” said Jim Muncy, the organization’s co-founder and policy chair.

While the amendments do not make major changes to NASA programs, some would require the agency to reconsider current plans. One amendment directs NASA to study boosting the ISS into a higher “safe orbital harbor” at the end of its operational life rather than deorbiting it, which is the agency’s current plan.

“The amendment does not mandate such a relocation, nor does it authorize construction funding or execution of any such plan,” said Rep. George Whitesides, D-Calif., who introduced the amendment with Rep. Nick Begich, R-Alaska. Instead, he said, it would allow Congress to better understand end-of-life options for the station.

“At a time when we’re thinking seriously about sustainability in space, this amendment protects taxpayer investment and ensures we fully understand our options before an irreplaceable asset is permanently retired,” Whitesides said.

A few amendments were introduced and then withdrawn. One, offered by Reps. Don Beyer and Suhas Subramanyam, D-Va., would have directed NASA to study the cost and risk of a “space vehicle transfer” funded in a budget reconciliation bill enacted in July and to require NASA to prevent physical harm to the spacecraft.

While last year’s legislation did not identify a specific vehicle, the space shuttle Discovery, currently displayed at the Smithsonian’s Udvar-Hazy Center in Northern Virginia, has since been identified as the likely spacecraft to be moved to Space Center Houston.

Beyer said he withdrew the amendment with the understanding that he would work with Babin “to make sure a meaningful space vehicle can be moved to Texas without damaging the vehicle.”

“I think we can ensure that we find a solution to this problem,” Babin said.

The only amendment rejected was one offered by Rep. Haley Stevens, D-Mich., that would authorize NASA to deploy systems to detect and counter unmanned aircraft systems at its facilities, including launch sites.

“We have growing threats to astronaut safety, launch operations and some of the most sensitive space technology,” Stevens said, citing a 20% increase in drone incursions into NASA-controlled airspace in 2025 compared with 2024. She said the offered the amendment at the urging of agency officials. “Our friends at the agency are asking for it.”

Republicans on the committee opposed the amendment, arguing that while they shared concerns about drone incursions, they believed the issue fell outside the committee’s jurisdiction.

“I think that we’re putting this into the wrong box,” said Rep. Pat Harrigan, R-N.C. “The proper committee of jurisdiction for this would be the House Armed Services Committee and the Senate Armed Services Committee.”

The amendment failed on an 18-19 vote along party lines, with Democrats in favor and Republicans opposed.

With committee approval, the bill now moves to the full House. Even if it passes there, it would need to be reconciled with any NASA authorization measure adopted by the Senate. A Senate NASA authorization bill was introduced last March but has not advanced out of the Senate Commerce Committee.

In the past 15 years, Congress has enacted only two NASA authorization laws, in 2017 and 2022. The latter was included in the broader CHIPS and Science Act rather than passed as a standalone bill.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly