Now Reading: How a sunlike star yanked down a teetering planet

-

01

How a sunlike star yanked down a teetering planet

How a sunlike star yanked down a teetering planet

Webb catches star consuming a planet for the 1st time

New observations from the James Webb Space Telescope might mark the first time astronomers have witnessed a parent star consuming one of its own planets. And it appears the doomed world was pulled down to its demise.

It’s a long-held belief among astronomers that aging sunlike stars will swell into red giants and consume their innermost planets. A recent study seemed to confirm the aging sunlike star had done just that. It was thought to have swollen into a red giant – the final life stage of a star like our sun – and consumed its planet as it grew to tremendous size.

Then data from Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) showed the star wasn’t bright enough to be a red giant. So something else must have caused the planet’s death. What astronomers were seeing was highly unusual. Lead author of the paper, Ryan Lau, described the findings in a statement from Webb. He said the team members had no idea what they might discover:

Because this is such a novel event, we didn’t quite know what to expect when we decided to point this telescope in its direction.

Lau is an astronomer at the National Science Foundation’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory (NOIRLab).

Planet’s death spiral lasted millions of years

The hungry sunlike star lies in a crowded area of our home galaxy, the Milky Way. It’s about 12,000 light-years from Earth. And it was first observed in 2020 at the Palomar Observatory in San Diego, Calif, as a transient flash of light. The brightening event was given the snappy name ZTF SLRN-2020.

Followup observations from Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (NEOWISE) showed the star had brightened at infrared wavelengths a year before the flash, a sign of the presence of interstellar dust. The conclusion was the star had been growing into a red giant over hundreds of thousands of years, swelling to 100 times its original size. And then it ate one of its own.

New Webb observations tell a very different story. MIRI was able to see the star more clearly, and it showed the star wasn’t bright enough to be a red giant. There wasn’t any end-of-life swelling.

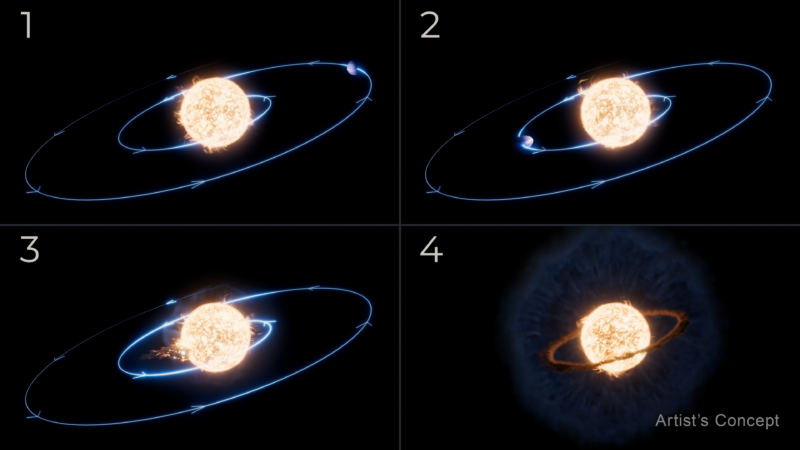

Instead, the Jupiter-size planet originally orbited very close to its star. It was even closer than Mercury is to our sun (36 million miles or 58 million kilometers on average). But the ill-fated planet’s orbit shrank. Over the course of millions of years, it spiraled ever closer to cosmic disaster.

Webb shows the doomed planet began to smear along its orbit

Stars are actually much larger than just the visible outer surface or photosphere. They extend millions of miles into the corona, a superheated atmosphere that surrounds all stars. When the planet met the corona – the source of coronal mass ejections (CME) – it was the beginning of the end, said astrophysicist Morgan MacLeod of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology:

The planet eventually started to graze the star’s atmosphere. Then it was a runaway process of falling in faster from that moment.

It wasn’t the heat that destroyed the planet. It was gravity. As the planet neared its final resting place, the tidal forces began pulling it apart. MacLeod said:

The planet, as it’s falling in, started to sort of smear around the star.

When it struck the star, the planet must have blasted away the star’s outer layers. When that matter cooled over the next year, some of it condensed into a surrounding cloud of cold dust.

Webb performs a stellar autopsy

The researchers anticipated finding the cooling dust that had been blown into space by the impact. But Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) detected a hot circumstellar disk of molecular gas closer to the star. In the disk, it found specific molecules, including carbon dioxide.

Colette Salyk, an exoplanet researcher at Vassar College and co-author of the study, said the star wasn’t forming planets and the discovery was a surprise.

With such a transformative telescope like Webb, it was hard for me to have any expectations of what we’d find in the immediate surroundings of the star. I will say, I could not have expected seeing what has the characteristics of a planet-forming region, even though planets are not forming here, in the aftermath of an engulfment.

This finding, as usual, created more questions than it answered. The team hopes to find more stars with planets teetering on the edge of destruction to learn more about what happens when a star eats a planet. Lau said:

This is truly the precipice of studying these events. This is the only one we’ve observed in action, and this is the best detection of the aftermath after things have settled back down. We hope this is just the start of our sample.

The team published their findings on April 10, 2025, in the Astrophysics Journal.

Bottom line: A Jupiter-size planet fell into its parent sunlike star, according to new data from the James Webb Space Telescope.

Read more: Nearby doomed stars spiraling toward a gigantic collision

Source: Revealing a Main-sequence Star that Consumed a Planet with JWST

The post How a sunlike star yanked down a teetering planet first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly