Now Reading: How are gas giant exoplanets born? James Webb Space Telescope provides new clues

-

01

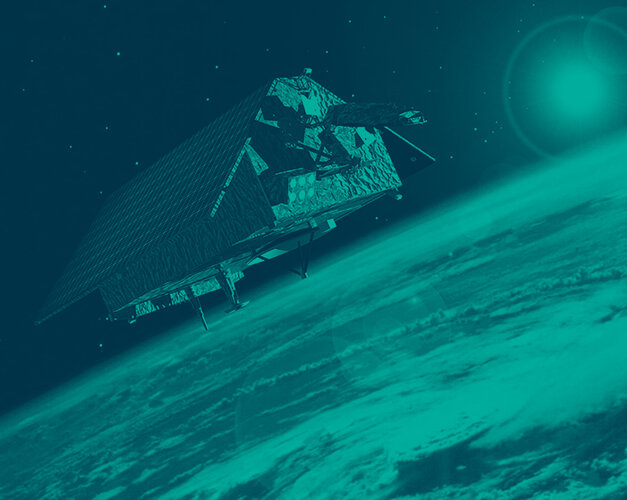

How are gas giant exoplanets born? James Webb Space Telescope provides new clues

How are gas giant exoplanets born? James Webb Space Telescope provides new clues

Astronomers may have just pushed the upper size limit of what counts as a planet, thanks to new insights into how giant worlds form.

New observations from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) suggest that even extremely massive gas giants — once thought too large to form like ordinary planets — may grow through the same basic process, shifting how scientists differentiate massive planets from brown dwarfs.

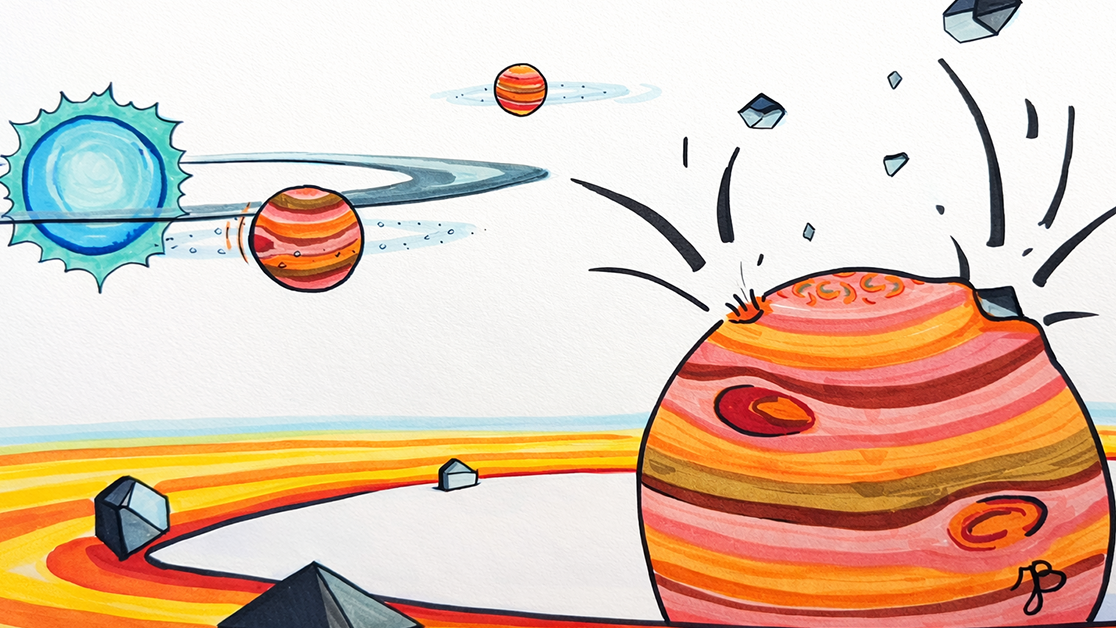

The findings come from a close look at the HR 8799 system, a young, sun-like star about 133 light-years from Earth that hosts four enormous gas giants orbiting far from their parent star. Each world is between five and ten times the mass of Jupiter — the largest planet in our own solar system — placing them near the fuzzy boundary between planets and brown dwarfs, which are substellar objects that fuse deuterium, rather than hydrogen like stars, earning them the nickname “failed stars,” according to a statement from the University of California, San Diego.

To test that assumption, the research team used the JWST’s powerful infrared spectrographs to analyze the chemical makeup of the planets’ atmospheres. Instead of focusing on common gases like water vapor or carbon monoxide, the scientists searched for sulfur-bearing molecules — elements that typically begin as solid grains in a young protoplanetary disk and thus suggest the planet formed through core accretion, according to the statement.

The spectral data provided by the JWST revealed hydrogen sulfide in the atmosphere of HR 8799 c, one of the system’s inner giants, providing strong evidence that the planet formed by first assembling a solid core before rapidly accreting gas. That chemical fingerprint is otherwise difficult to explain if the planet instead formed through a rapid, star-like collapse of gas. The team also found that the planets were more enriched in heavy elements, like carbon and oxygen, than their star, further supporting that they formed as planets.

“With the detection of sulfur, we are able to infer that the HR 8799 planets likely formed in a similar way to Jupiter despite being five to ten times more massive, which was unexpected,” Jean-Baptiste Ruffio, lead author of the study, said in the statement.

Therefore, the study suggests that core accretion can operate efficiently even at extreme masses and distances, expanding the known limits of the planet-building process. If confirmed in other systems, the finding could force astronomers to rethink where — and how — the line between giant planets and brown dwarfs is drawn.

Their findings were published Feb. 9 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly