Now Reading: How do you activate a supermassive black hole? A galaxy merger should do the trick

-

01

How do you activate a supermassive black hole? A galaxy merger should do the trick

How do you activate a supermassive black hole? A galaxy merger should do the trick

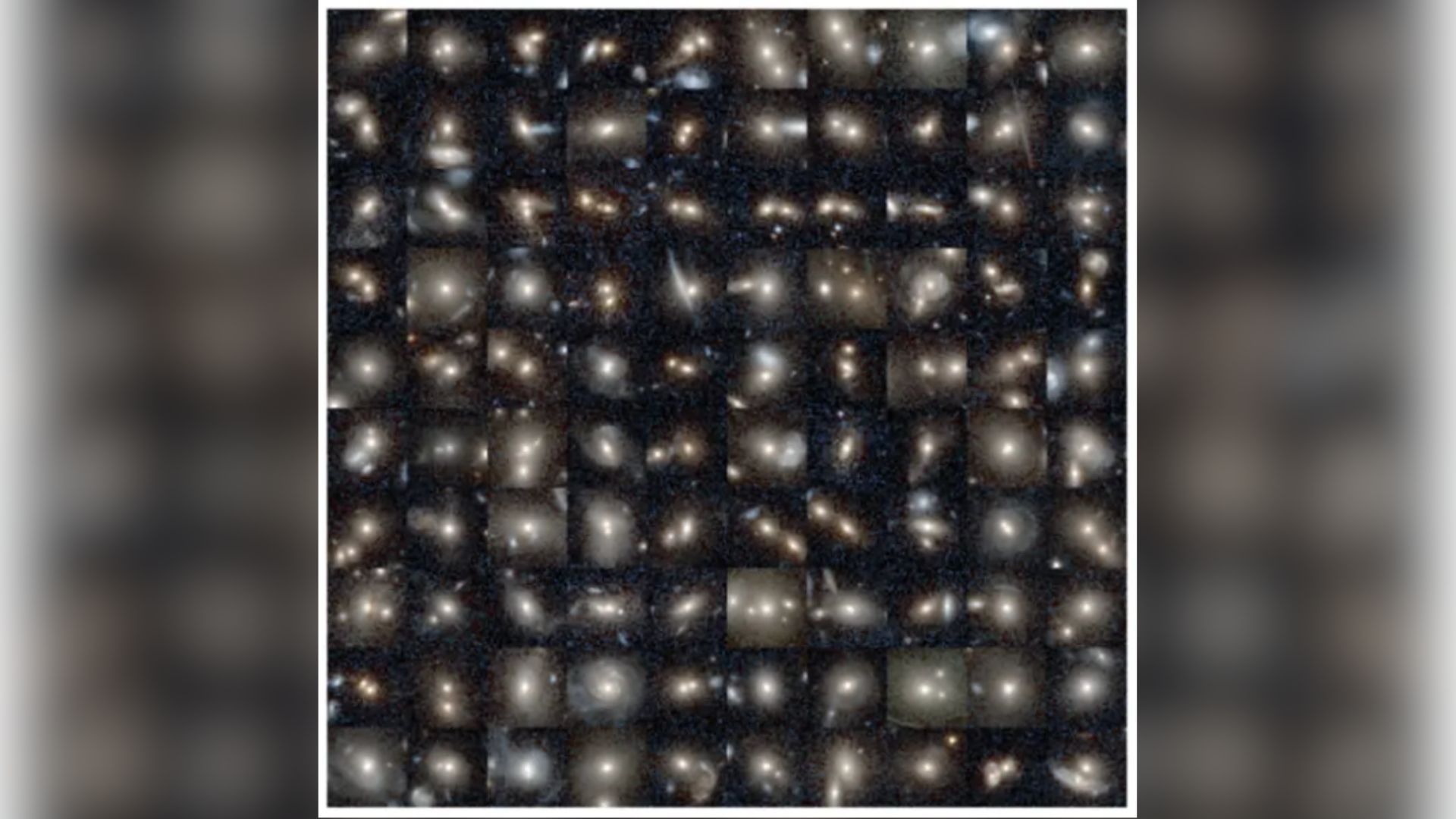

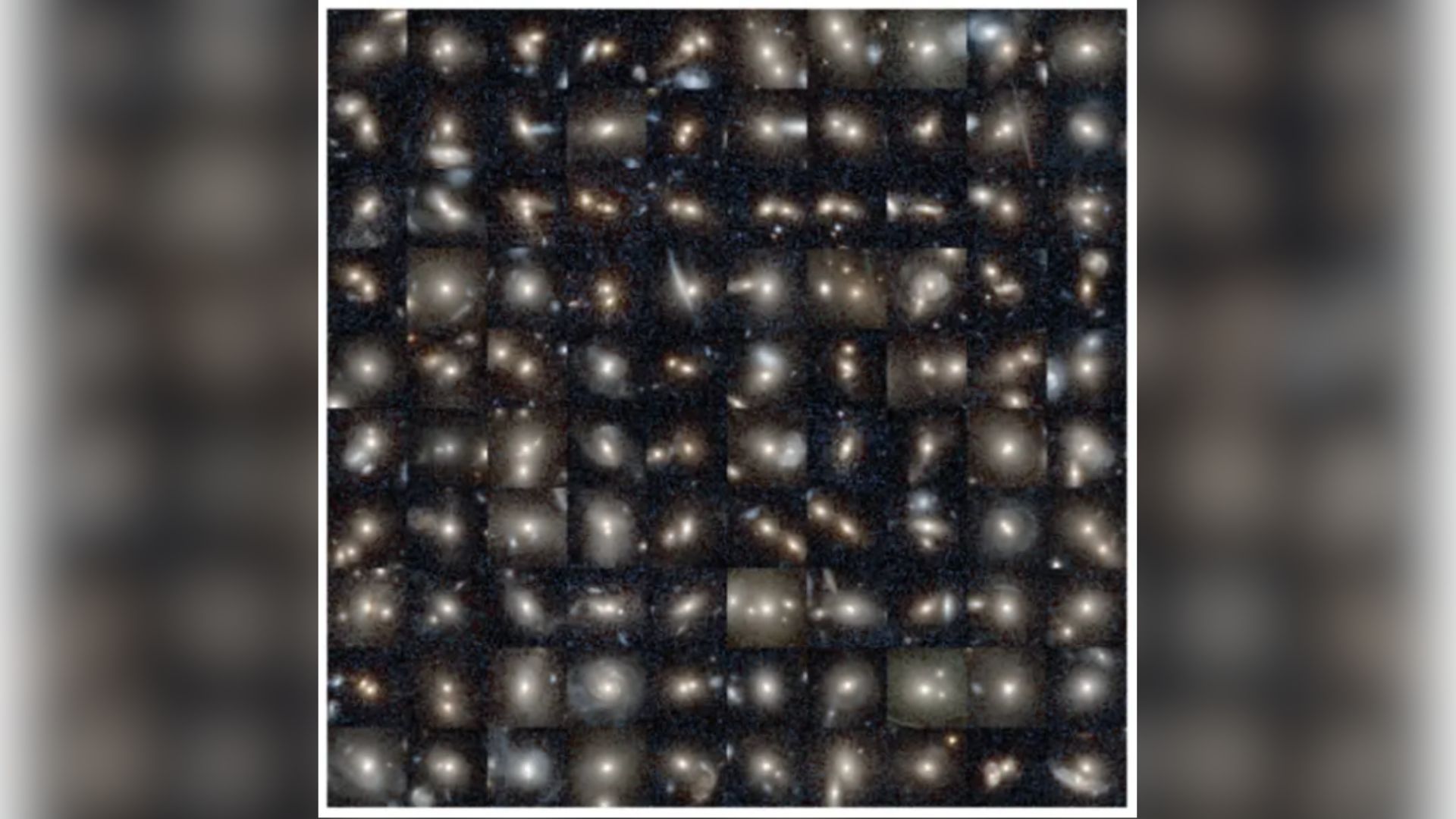

Scientists have confirmed that colossal collisions between galaxies trigger titanic eruptions in the centers of those galaxies, and the discovery is thanks to an artificial intelligence tool that was able to sort through images of a million galaxies to find those possessing a so-called active galactic nucleus, or AGN.

The results come courtesy of the Euclid space telescope, which is a European Space Agency mission that’s designed to study dark matter and dark energy by measuring and mapping billions of galaxies. Researchers took a “small” subset of a million of the galaxies Euclid is charting and used them to chronicle the causes of AGN.

It has long been strongly suspected that mergers play a crucial role in sparking AGN activity, because something needs to push all that gas into the nucleus of a galaxy, but suspecting and having confirmation are two different things. Validating this hasn’t been as easy as one might think, because the most powerful AGN are at a great distance from us (the closest quasar is 3C273, which is 2.3 billion light-years away) and clearly resolving galaxies at such distances so that we can see that they are definitely merging has been difficult. While the Hubble Space Telescope and James Webb Space Telescope can resolve them, they don’t cover a wide enough area of sky to be able to image enough to obtain a census.

Following its launch in 2023, Euclid has changed all that. With its 1.2-meter telescopic mirror, 600 megapixel camera and wide field of vision, in just one week it can provide higher quality images than most other telescopes while covering an area of sky similar to the total area that has been observed by the Hubble Space Telescope during its entire 35 years in service.

Astronomers in the Euclid Collaboration divided the million galaxies seen by Euclid into two categories: one where the galaxies appear to be merging, and one where no merger is taking place.

They then employed an artificial intelligence image decomposition tool developed by Berta Margalef-Bentabol and Lingyu Wang from SRON, the Netherlands Institute for Space Research, to identify AGN in these galaxies and even quantify their power output to determine which are the most energetic.

“This new approach can even reveal faint AGN that other identification methods will miss,” said Margalef-Bentabol in a statement.

The team found that there were between two and six times as many AGN in galaxies in the category of mergers than those not experiencing a merger.

In the case of mergers that have begun relatively recently and which have kicked up a lot of interstellar dust such that it shrouds the nucleus, making it only visible in infrared light, there are six times more AGN. In the case of mergers that are nearing their end stages and in which the dust has all settled, there are still twice as many AGN than in the non-merger galaxies.

“The difference between the two AGN types could mean that many AGN found in non-mergers are actually in merged galaxies that have completed the chaotic stages and appear as a single galaxy in a regular form,” said Antonio la Marca of the University of Groningen.

The observational evidence not only heavily supports the concept of mergers being a trigger of AGN activity, but also indicates that mergers are the primary cause, particularly for the most luminous AGN.

“We also conclude that mergers are very likely to be the only mechanism capable of feeding the most luminous AGN,” said la Marca. “At the very least they are the primary trigger.”

AGN represent the most rapid growth phase of supermassive black holes, and the outpouring of radiation from these gluttonous black holes can heat the molecular gas in a galaxy, preventing it from forming stars. AGN can therefore have a long-term impact on their host galaxy, and understanding that the host is likely to be merging is important to know when modeling the evolution of galaxies.

The findings are set to be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, and are available as two pre-prints, one detailing the analysis of merging galaxies and AGN, and the other describing the AI image decomposition tool.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly