Now Reading: How old is Jupiter? Meteorite ‘raindrops’ help scientists pin down gas giant’s age

-

01

How old is Jupiter? Meteorite ‘raindrops’ help scientists pin down gas giant’s age

How old is Jupiter? Meteorite ‘raindrops’ help scientists pin down gas giant’s age

In some cases, to learn more about our solar system, all we have to do is look at evidence found on Earth.

Researchers from Japan’s Nagoya University and the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) have determined how mysterious molten “raindrops” in meteorites formed — and used that information to date Jupiter’s formation.

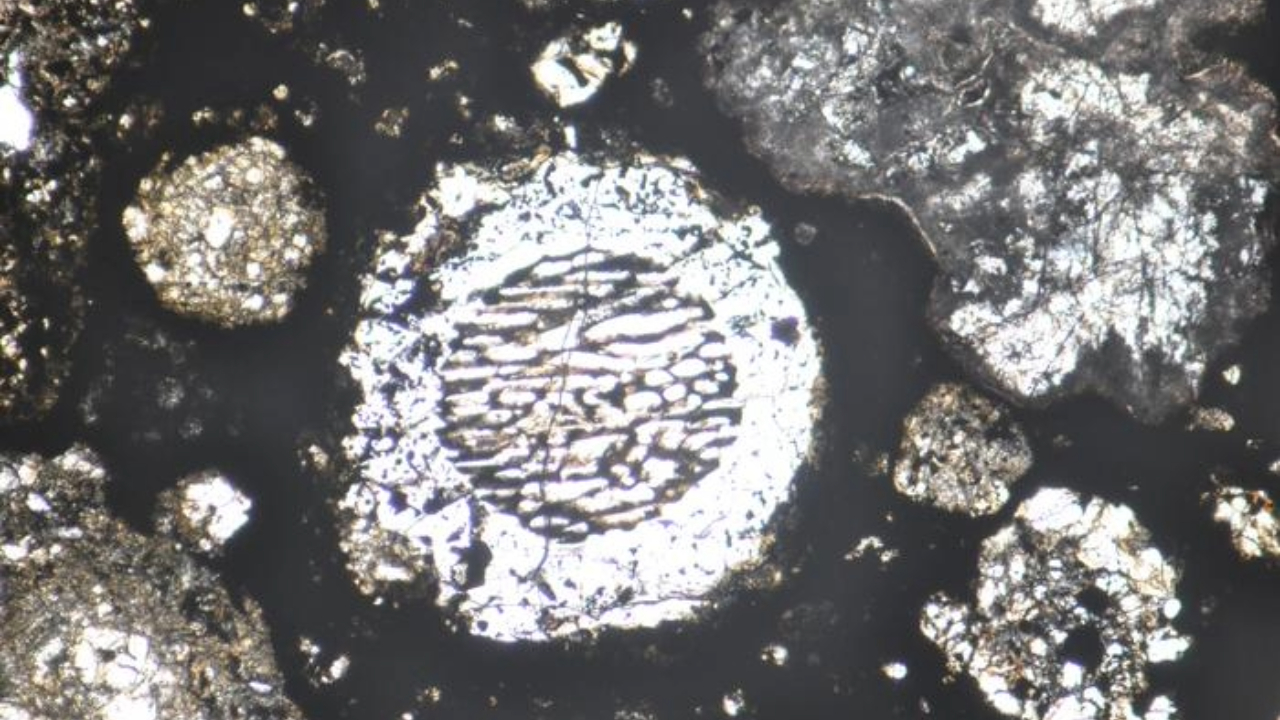

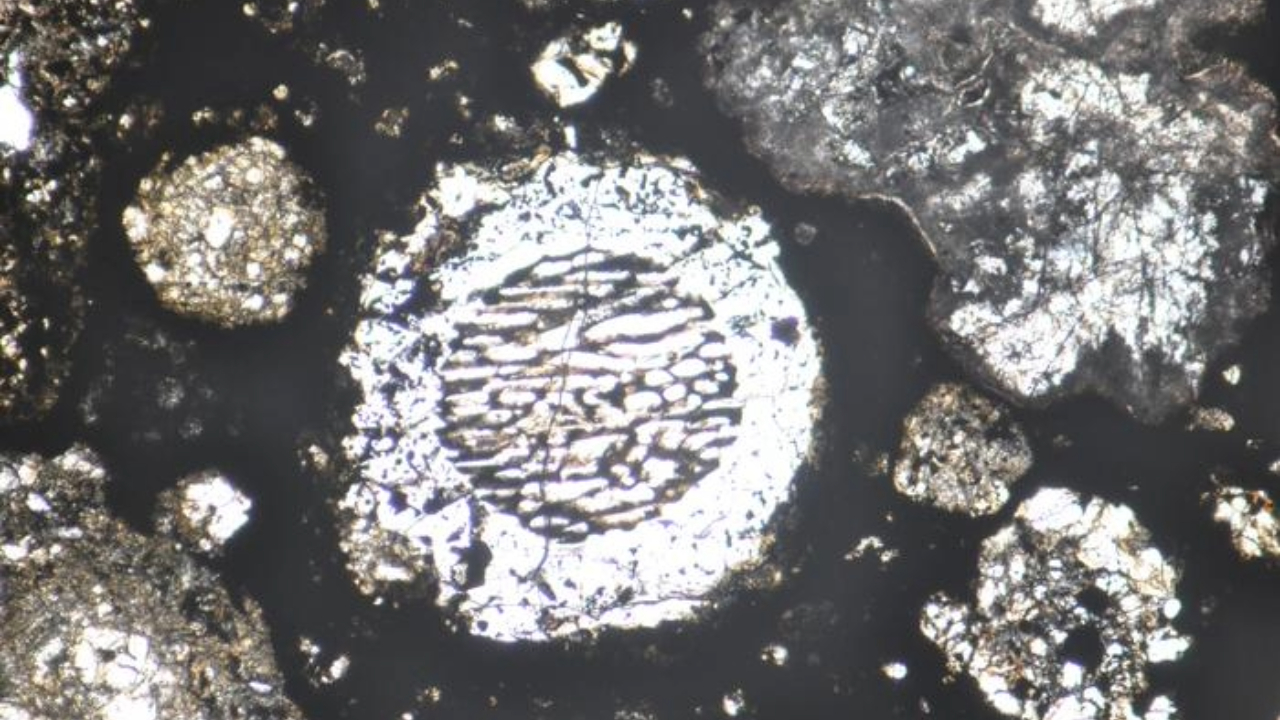

The raindrops are called chondrules. They’re strange spherical droplets of molten rock just 0.1 to 0.2 millimeters wide, found in a specific type of meteorite called a chondrite. Until now, no one knew how their round shape formed.

It all began a long, long time ago, not in a galaxy far, far away, but in our very own Milky Way. In the chaotic environment of our young solar system, small rocky and icy bodies called planetesimals crashed into one another at high speed.

“When planetesimals collided with each other, water instantly vaporized into expanding steam. This acted like tiny explosions and broke apart the molten silicate rock into the tiny droplets we see in meteorites today,” study co-lead author Sin-iti Sirono, a professor at Nagoya University, said in a statement.

It turns out that Jupiter was the key to unlocking the mystery. “Previous formation theories couldn’t explain chondrule characteristics without requiring very specific conditions, while this model requires conditions that naturally occurred in the early solar system when Jupiter was born,” said Sirono.

Using computer models to simulate Jupiter’s early, rapid growth, the researchers discovered that its gravity whipped the planetesimals into a frenzy, causing the high-speed collisions that created the chondrules.

“We compared the characteristics and abundance of simulated chondrules to meteorite data and found that the model spontaneously generated realistic chondrules,” said co-lead author Diego Turrini of INAF.

Related Stories

In addition, the model helped date Jupiter’s formation more precisely, to 4.6 billion years ago.

“The model also shows that chondrule production coincides with Jupiter’s intense accumulation of nebular gas to reach its massive size,” said Turrini. “As meteorite data tell us that peak chondrule formation took place 1.8 million years after the solar system began, this is also the time at which Jupiter was born.”

Fortunately, the story isn’t over. While this Jupiter-based model explains the creation of some chondrules, there are others with different ages. It’s likely that the formation of other planets, including Saturn, contributed to these chondrules. And that means it’s time for some more research.

The team’s research was published in the journal Scientific Reports on Aug. 25.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly