Now Reading: How SpaceX turned a Texas marsh into the world’s most watched spaceport

-

01

How SpaceX turned a Texas marsh into the world’s most watched spaceport

How SpaceX turned a Texas marsh into the world’s most watched spaceport

EDITOR’S NOTE: Starbase is SpaceX’s massive rocket development site and the home of Starship — the vehicle Elon Musk envisions as humanity’s path to Mars and that many in the U.S. civil space program see as a way back to the moon. But Starbase started as little more than an impossible stretch of empty land along the South Texas coast.

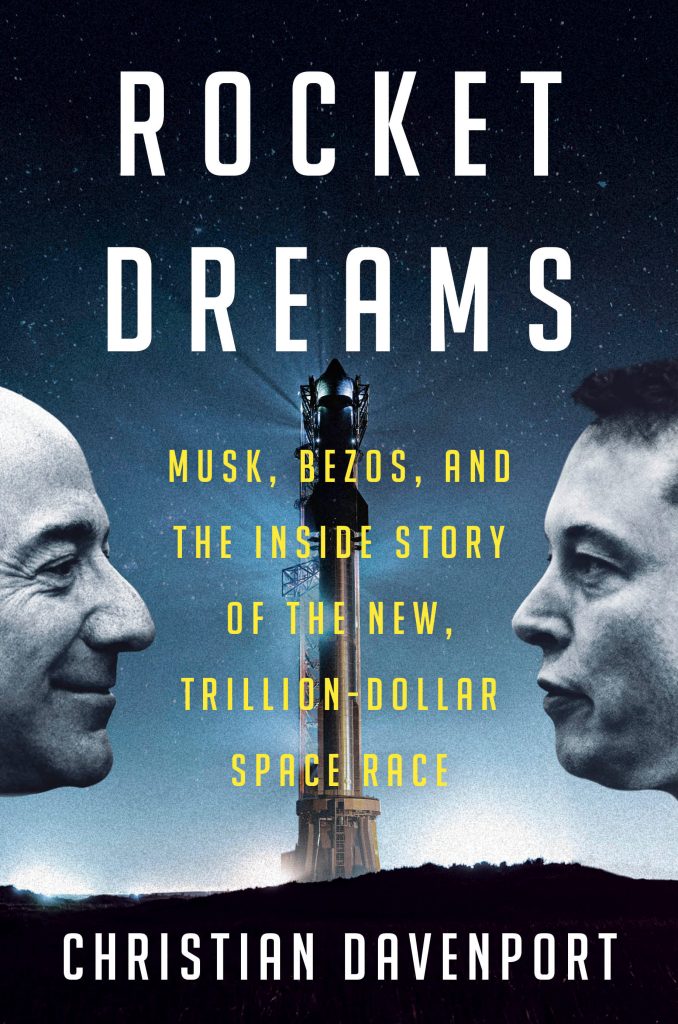

The following is an excerpt from Christian Davenport’s new book Rocket Dreams, released today (Sept. 16), which tells the inside story of the trillion-dollar space race.

The team Elon Musk had dispatched to scout a new launch site in South Texas in 2011 drove along a two-lane road out of Brownsville that ran past a Border Patrol checkpoint, past a gun shop and firing range, through a wildlife protection area and a state park, and finally arrived at the Gulf of Mexico. There they parked and surveyed what was one of the most bizarre places they had ever been. There was no electricity, no Internet. Water surrounded them, and the land was low. One good Gulf-fueled hurricane would wash everything away. The ground was porous and soft, the consistency, in some places, of Jell-O.

The group — engineers Tim Buzza, Hans Koenigsmann and Steve Davis, and Caryn Schenewerk, an attorney who served as SpaceX’s director of legislative affairs in the company’s Washington, D.C., office — was stunned. How would they ever launch a rocket from here?

I guess we’ll have to launch at low tide, Buzza was thinking, just as Border Patrol agents pulled up in a truck, demanding to know what they were doing. Buzza wasn’t sure how to respond. “If we said we were looking for a super-heavy launch site to get to Mars, they would have detained us,” he later recalled. Instead, they said something about looking for land for commercial purposes.

The agents said they should be on their way. But before the SpaceX team left, they turned into a one-street residential village called Boca Chica, a tiny hamlet that didn’t show up on most maps, whose few residents made it clear they cherished their lonely quiet and end-of-the road anonymity.

Half of the homes looked abandoned. There seemed to be more barking dogs than people. Since the residents had no running water, they relied on the county to truck it in once a month in big blue barrels that sat on their lawn. Buzza stepped forward to get a better look at one house, then quickly retreated after seeing a sign that read, “MEET MY FRIEND SMITH AND MY OTHER FRIEND WESSON.”

Boca Chica was on the water, but the Gulf of Mexico was not the vast, empty Atlantic Ocean. Any rocket launching from Boca Chica could in a matter of minutes find itself over Florida or Cuba. To protect the people who lived there from the possibility of falling shrapnel, the rockets would have to bank right, like a golfer hitting a slice on the drive of a dogleg par-four.

The site’s other neighbors posed a problem as well. The land was situated between a Texas State Park and a U.S. Fish and Wildlife refuge, home to the piping plover: a diminutive, at-risk shorebird vigorously defended by environmentalists who would, no doubt, object to a rocket business moving into the neighborhood.

Even if SpaceX were able to somehow solidify the spongy soil, if it could acquire the property and buy out the nearby residents, if it could find a way to launch without flying over Florida, it would still have to build the infrastructure — rocket pads, manufacturing sites — from scratch. The launch facilities it used on Cape Canaveral and Vandenberg Air Force Base might have been fixer-uppers, but at least the basic necessities were there. At Boca Chica there was nothing; it was an empty canvas of waterlogged sand.

When Buzza returned to SpaceX and gave Musk his report, he didn’t sugarcoat the challenges. He laid out every one — the floodplain, the lack of services, the environmental concerns, the soft, marshy land. The degree of difficulty was a 10. But then again, so was everything SpaceX had ever done. The degree of difficulty in starting a space company from scratch was a 10. So was building a rocket capable of getting to orbit. So was building a rocket that could fly back from orbit and land on Earth so it could be reused.

Buzza knew a challenge would not deter Musk. He’d only want to know: Was it possible? Could SpaceX build a launch site there?

The answer, Buzza believed, was yes.

Musk nodded and listened quietly as Buzza reeled off all the problems, and said finally, “Okay, let’s tackle them one by one.”

The first hurdle was to acquire the land — quietly. SpaceX did not want people to know it was scouting real estate in South Texas and drive up the price. A small team, led by Steve Davis, one of Musk’s most trusted confidants, looked at the real estate possibilities. They started poring over county property records and decided against hiring the real estate agent they had interviewed, concluding they were more adept at locating opportunities than she appeared to be.

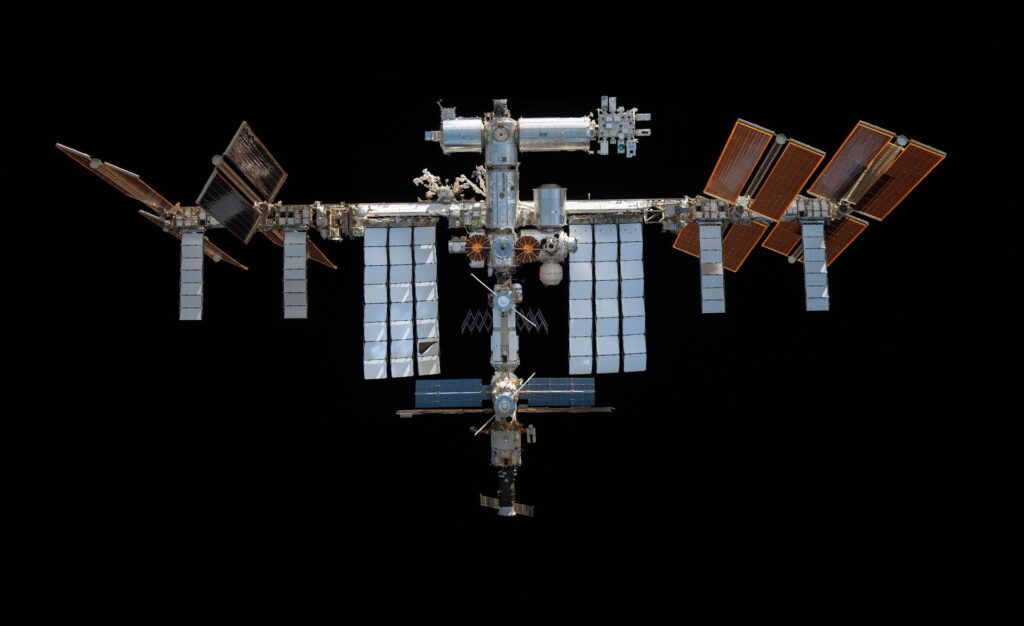

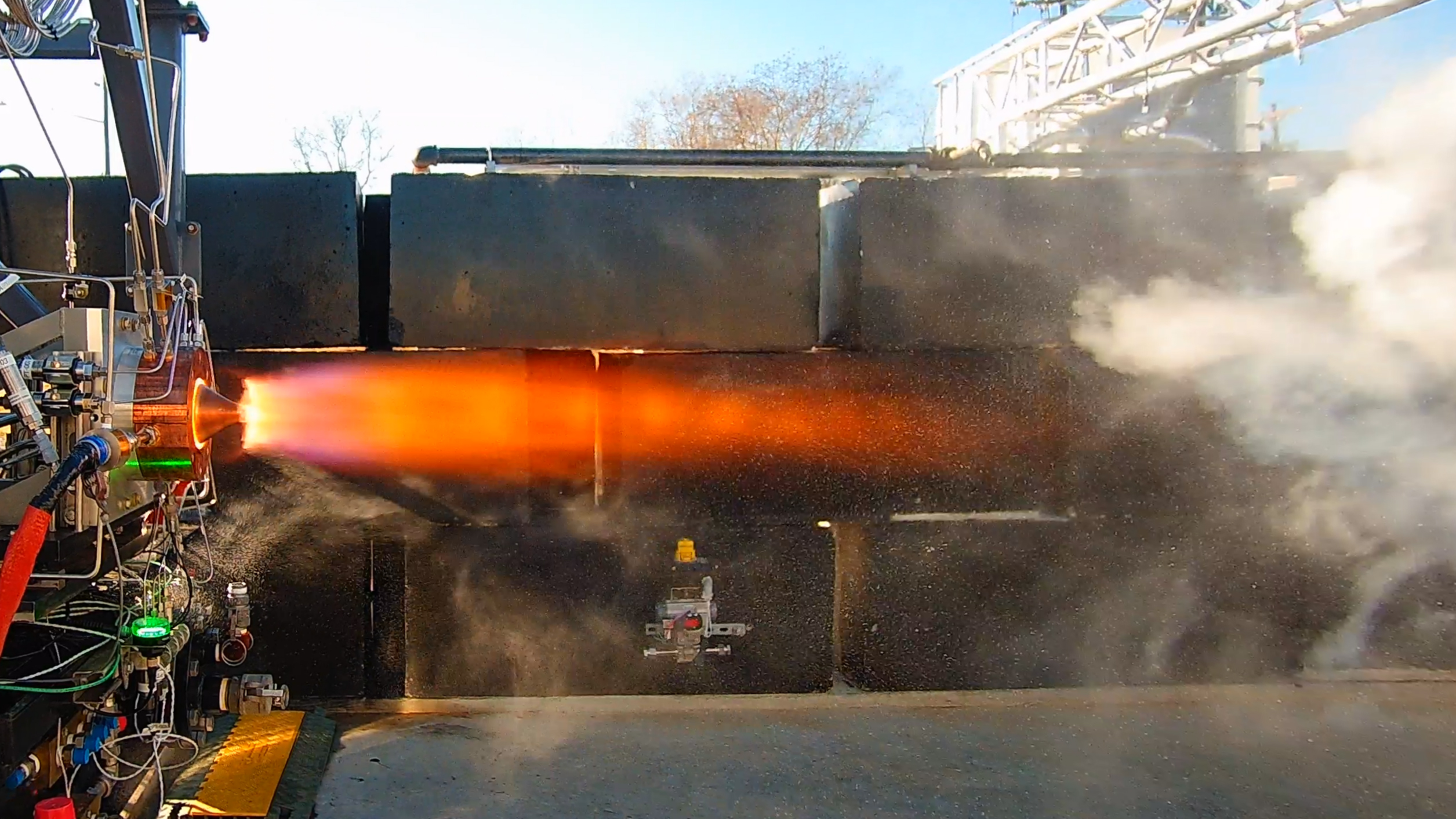

Working from county rolls, they made cold calls and wrote letters asking people to sell — never mentioning SpaceX, of course. Even Davis, one of SpaceX’s most hardcore engineers, was intimately involved. He had impressed Musk in his initial interview by solving what he later called “math-based technical brain teasers” in his head, and then spent years immersed in developing the Dragon capsule’s propulsion systems, avionics and heat shield. He also helped write the software that would allow the self-driving capsule to autonomously dock with the International Space Station. Later, he’d be dispatched to revamp Twitter after Musk purchased it, and then to slash the size of the federal government as part of Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency. But now the Boston-born, Penn- and Stanford-educated wonder kid had tapped a skill set no one, including himself, knew he possessed. The aerospace engineer transformed himself into a real estate prospector, dialing random property owners and charming them into selling him their land, as if he were amassing a portfolio of penny stocks.

One advantage SpaceX had was that many of the properties were delinquent on their taxes, or the owners were dead, meaning many parcels were just sitting there vacant, contributing nothing to the county’s already depleted coffers and undesirable to everyone but the apparently delusional CEO of an emerging space company. The first purchase was recorded in the Cameron County property database on June 6, 2012 — just over half an acre for $2,500 from the local school district. The buyer used the address of SpaceX headquarters, at 1 Rocket Road in Hawthorne, California, but not the company’s name. Instead, it was Dogleg Park LLC, a curious moniker chosen by Schenewerk in honor of the turn the rockets would have to make after launching from Boca Chica to avoid flying over land.

In September of that year, SpaceX bought a couple more properties, this time at auction: one for $6,400 and the other for $15,000. This time a name was recorded alongside Dogleg Park: Lauren Dreyer, SpaceX’s 31-year-old director of business affairs and compliance. By then, Emma Perez-Trevino, a reporter for The Brownsville Herald, was on to SpaceX. On September 23, she broke the news that the company was snatching up land. “Public Records Show Local Purchases for Musk’s Company,” read the headline. She followed up with another story in November: “Land Grab: SpaceX Buys More Land Near Boca Chica.”

Now that the word was out, SpaceX had to move fast to avoid a land rush. When Cameron County held another auction for tax-delinquent properties a few months later, SpaceX snatched up nine more. An employee dispatched to the county courthouse became a regular fixture at the auctions, one hand on the paddle ready to bid, the other holding a cell phone, with Davis on the other end at his desk in the D.C. office, instructing her on how high to go. SpaceX created another shell company — The Flats at Mars Crossing — but it didn’t take long for the area land investors to figure out who the employee was working for. “Hey, rocket girl,” they taunted. “We’re going to beat you, and you’re going to have to buy it from us for three or four times the amount.”

On at least one occasion, Dreyer came down to help out at the auctions. But, worried that she’d be recognizable as the SpaceX employee helping to lead the development effort in South Texas, she arrived at the auction in disguise. She wore a wig to cover her blond hair; large Jackie O. sunglasses to shield her blue eyes; and a colorful poncho.

After Musk announced that SpaceX would build its private spaceport in South Texas, the governor and dignitaries from across the state traveled to South Texas to celebrate with a ceremonial groundbreaking with Musk. The few employees on-site scrambled to get it ready and even hired a local resident who, to their surprise, cut the waist-high grass while wearing only a pair of boxer shorts. To keep everyone out of the sun, SpaceX erected a tent and, for the VIPs, an RV with air-conditioning.

Musk, as usual, was running late. His private jet had landed at the Brownsville airport about a half hour away, and a police escort had been arranged. But he was just sitting on the plane, apparently immersed in a phone call. SpaceX employees started growing nervous their guests would be offended — or melt. It was ridiculously hot. Everyone was sweaty and uncomfortable, and some supersized species of Texas mosquito was out in force. One stung a young SpaceX government liaison staffer on the forehead, drawing blood that dripped onto his pressed white dress shirt.

Finally Musk arrived, and despite his tardiness he was greeted with enthusiasm, a messiah from Silicon Valley who would spark an economic revival in a region that desperately needed it. The effort symbolized the state’s “pioneer heritage,” Gov. Rick Perry crowed, and “our tradition of thinking bigger, dreaming bolder and daring to the impossible.”

Wearing a white shirt open at the collar and a dark suit, Musk was in a great mood, basking in the attention. The long-term goal of SpaceX, he said, “is to create the technology necessary to take humanity beyond Earth, to take humanity to Mars and establish a base on Mars. It could very well be that the first person that departs for another planet could depart from this location.” But he warned that rockets wouldn’t be shooting from the site anytime soon. “It is going to take several years to build out a spaceport because this is going to be quite a significant building endeavor,” he said. Standing side-by-side, Musk and Perry hoisted the first ceremonial shovelfuls of dirt.

With the ceremony concluded, SpaceX’s engineers got to work transforming the swampy marsh into a launch site. They drilled down hundreds of feet, then more than a thousand, but couldn’t find bedrock. “All we got were alternating layers of silt and sand, silt and sand,” one former employee recalled. At one point an excavator got swallowed up by a sinkhole. Employees spent days trying to get it out, but it only sank more. Finally, they rigged the heavy piece of machinery to two bulldozers and a thirty-ton dump truck and got it out right before a rainstorm that would have made it impossible to save.

What SpaceX needed was more dirt. A lot more. In 2015, crews started hauling it in with a constant stream of heavy trucks that rumbled down Route 4 and left the lonely road pockmarked with potholes. The effort took months. Eventually, 310,000 cubic yards, or enough to cover the area of a football field fourteen stories high, stood on the site as a man-made mesa.

In a process known as “soil surcharging,” the giant pile would slowly compress the soil beneath it, eventually to a density that could serve as a foundation solid enough for rocketry. But that would take years.

Mars, or any rocket launch from Boca Chica, would have to wait.

Christian Davenport has been a staff writer at The Washington Post for more than 25 years and is also the author of “The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos.”

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

04Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

04Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

05Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

05Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits