Now Reading: Icy moons in our solar system may have boiling oceans — but life could potentially still survive

-

01

Icy moons in our solar system may have boiling oceans — but life could potentially still survive

Icy moons in our solar system may have boiling oceans — but life could potentially still survive

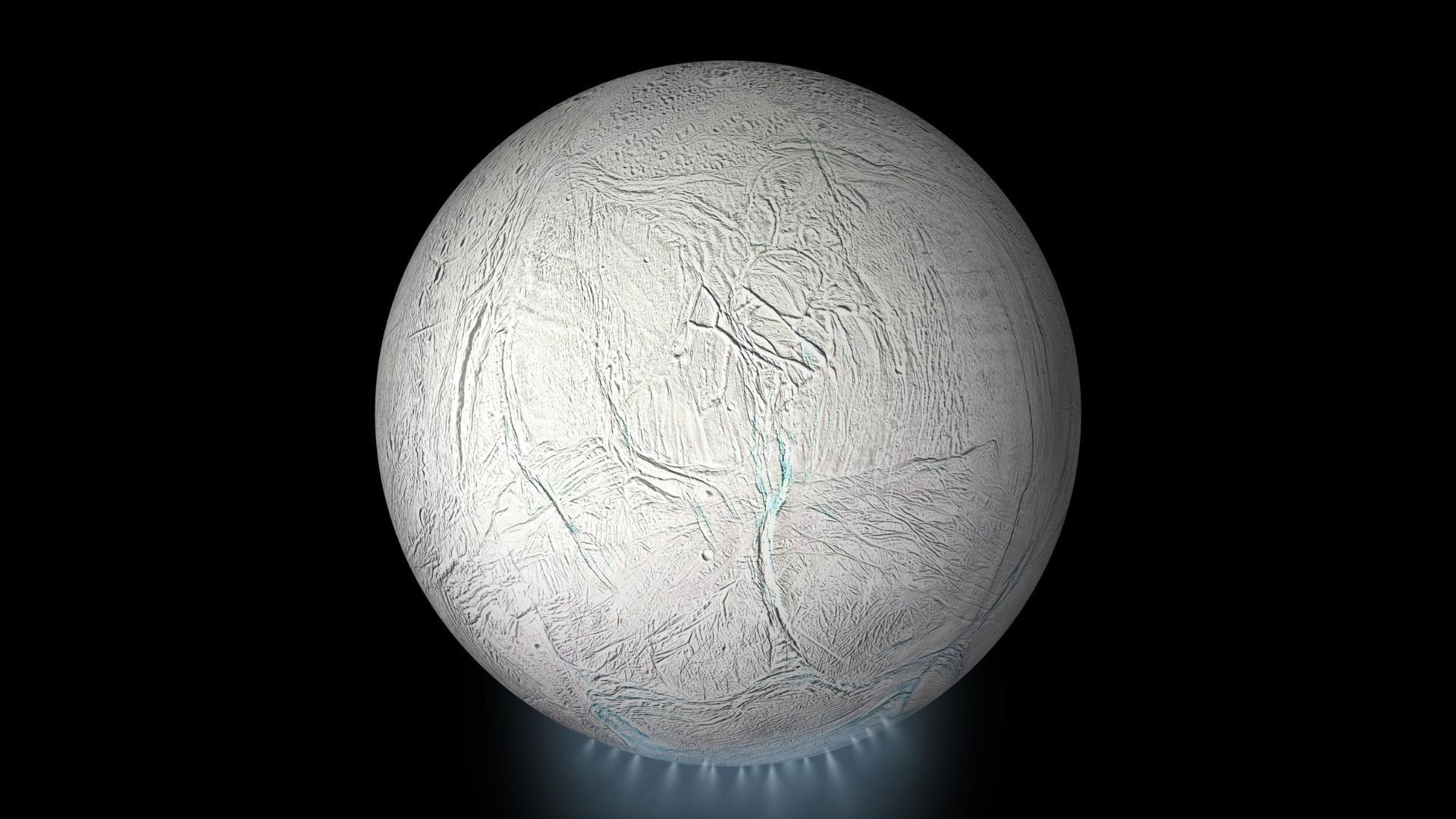

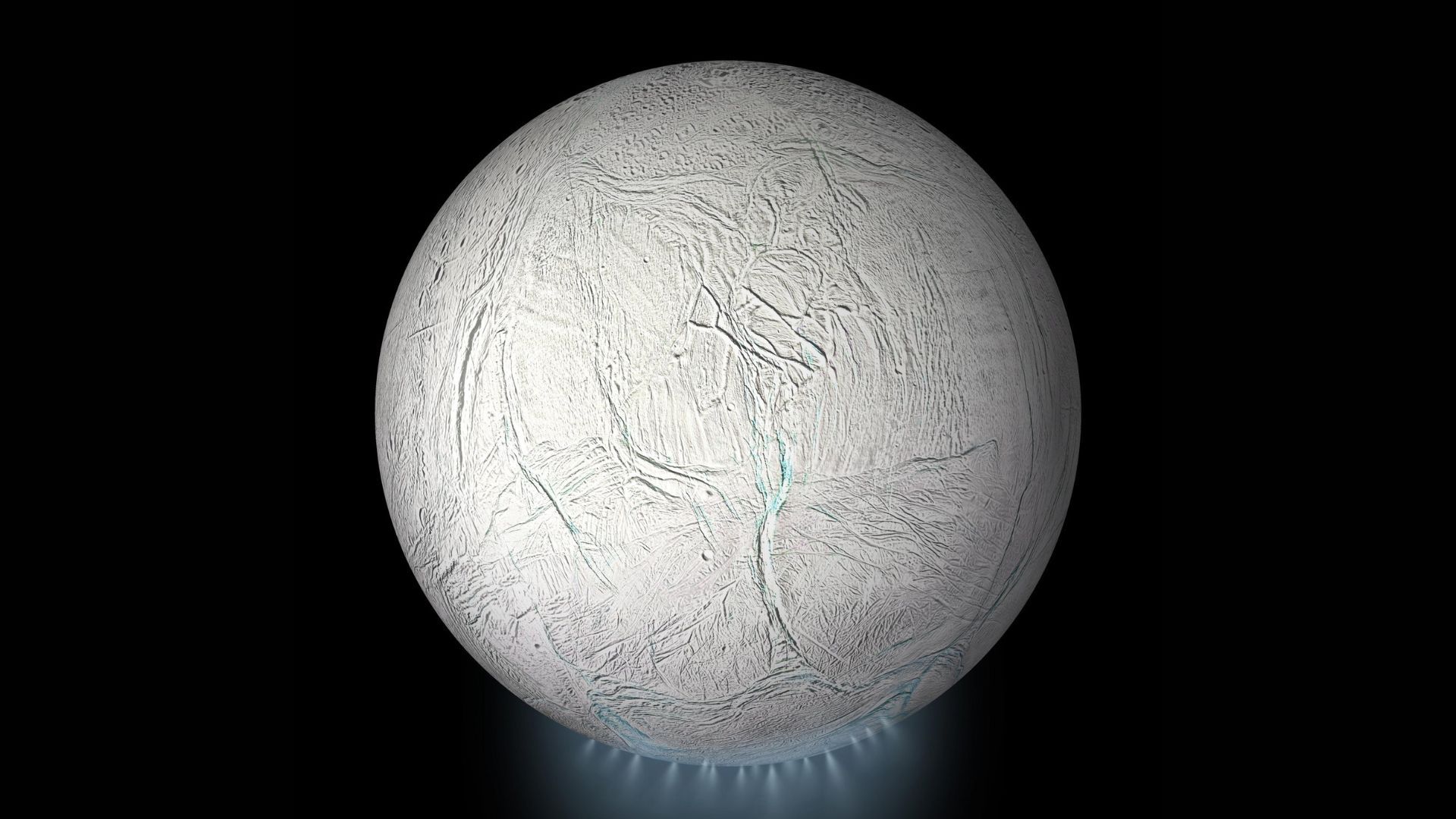

Small icy moons in the outer reaches of our solar system may hide boiling oceans underneath their surfaces, a new study finds.

Previous research found that some of the icy moons in the outer solar system, such as Saturn’s moon Enceladus, are not frozen solid. Instead, they may host oceans between their ice shells and rocky cores. Because on Earth, there is virtually life wherever there is water, this has raised the hope that such hidden oceans may be the best sites in our solar system to look for extraterrestrial life.

“We were especially interested in whether the stresses could lead to the formation of cracks that connect the surface to the subsurface ocean, allowing the eruption of liquid water from a potentially habitable ocean to space,” Rudolph told Space.com.

In prior work, Rudolph and his colleagues focused on what happens to these moons when their ice shells get thicker. As ice takes up a greater volume than a similar mass of liquid water, freezing places pressure on ice shells, generating features such as the “tiger stripes” seen on Enceladus.

In the new study, the researchers explored what happens when the icy shells of these moons become thinner due to melting from the bottom. For instance, previous research discovered a wobble in the orbit of Saturn’s moon Mimas was potentially due to an ocean under its icy crust that likely arose in the past 10 million years, given how its surface still retains many ancient features, such as craters. This ocean likely resulted when Mimas’s shell melted due to interactions with other Saturnian moons.

The scientists discovered that if these icy shells thin, the pressure they place on the oceans drops. On the smallest icy moons, such as Mimas and Enceladus or Uranus’s Miranda, the pressure could lower enough to reach a so-called “triple point” — a specific combination of temperature and pressure in which ice, liquid water and water vapor can all co-exist. This can lead the layers of the oceans closest to their icy shells to boil after the icy shells thin by about three to nine miles (five to 15 kilometers).

“This is the kind of boiling that happens at low temperatures, not the kind of boiling that occurs in kitchens when you heat water up to past 100 degrees C [212 degrees F],” Rudolph said. “It’s instead boiling very close to zero degrees C [32 degrees F]. So for any potential life forms below that boiling area, life could go on as usual.”

In contrast, on larger ice moons more than 370 miles (600 km) wide, such as Uranus’s Titania, the drop in pressure from melting ice would instead cause the ice shell to crack before the triple point for water is reached, the team calculated. The researchers suggest that features of Titania’s geology, such as wrinkle ridges, might have resulted from a period of ice shell thinning followed by re-thickening.

The gases from boiling might have a number of effects, such as the formation of clathrates — complex icy structures that entrap gas molecules. “Future work will address these processes in detail to understand what happens to gas once it has been released from an ocean and what kinds of surface features we would expect to form in association with these processes,” Rudolph said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Nov. 24 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

05True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors