Now Reading: International Space Station prepares for new commander, heads into final five years of planned operations

-

01

International Space Station prepares for new commander, heads into final five years of planned operations

International Space Station prepares for new commander, heads into final five years of planned operations

After 25 years of continuous human presence, the International Space Station is heading into its final half decade of planned habitation.

NASA and its international partners are planning to intentionally deorbit the orbiting laboratory around 2030 or shortly thereafter. SpaceX was contracted valued at up to $843 million to build the United States Deorbit Vehicle (USDV), which will help guide the space station towards a splashdown in an uninhabited portion of the Pacific Ocean.

On Sunday, Dec. 7 NASA astronaut Mike Fincke will assume the role of ISS Commander, taking over from Russian cosmonaut Sergey Ryzhikov. The cosmonaut along with his colleague, Alexey Zubritsky and NASA astronaut Jonny Kim, will then board their Soyuz spacecraft and undock Monday evening to complete their 245-day mission in orbit.

With funding from the recent budget bill from Congress and renewed promise from NASA Administrator nominee Jared Isaacman to “maximize the scientific value of every dollar that Congress affords the agency,” the space station will continue to be a bustling hub of science for its final five years.

On Thursday, the Center for the Advancement of Science in Space (CASIS) announced an extension of its cooperative agreement with NASA to allow the non-profit to continue managing the ISS National Laboratory through 2030. This allows CASIS, through the ISS National Lab, to continue managing up to 50 percent of the flight allocation on cargo missions and up to 50 percent of U.S. Operating Crew time for science backed by them.

The ISS National Lab backed more than 940 payloads launched to the space station during the period of CASIS management, which began in 2011.

“For nearly 14 years, NASA has entrusted CASIS with managing this incredible asset for our nation and for the benefit of humanity,” said Ramon (Ray) Lugo, principal investigator and chief executive officer of CASIS. “We are honored that NASA has extended this unique partnership through 2030, and we will continue to work in collaboration, pushing the limits of space-based R&D for the benefit of life on Earth while driving a robust and sustainable market economy in space.”

Going to and fro

While the science planned for the ISS is in no short supply, the methods of getting it and its inhabitants to and from the space station is a trickier matter.

The most recent wrinkle came in the wake of the Soyuz MS-28 launch. After NASA astronaut Chris Williams along with Russian cosmonauts Sergey Kud-Sverchkov and Sergei Mikaev, the mobile service platform, which allows technicians access to the engine section of the rocket prior to launch, collapsed into the flame duct at Site 31.

According to Russia-based journalist, Anatoly Zak, there are varying estimates of how long repairs could take, with at least one source telling him that it could take “up to two years” and that the immediate path forward wasn’t clear.

Sources: Roskosmos has a spare service platform similar to the one that crashed after Soyuz liftoff Thursday, however its installation will require a major work at the pad.

Updates: https://t.co/0e2wF3URfl pic.twitter.com/V80KhNgFm2— Anatoly Zak (@RussianSpaceWeb) November 30, 2025

In a statement published to its official Telegram account, Roscosmos said that the damaged would be fixed “in the nearest time,” but didn’t provide details. Spaceflight Now reached out to the Russian space agency for comment and is waiting to hear back.

For its part, NASA mostly diverted questions to Roscosmos. Russia’s Progress cargo spacecraft not only deliver supplies but also propellants for the Russian-side of the complex, used to maintain the station’s orbital altitude and also to assist with attitude control.

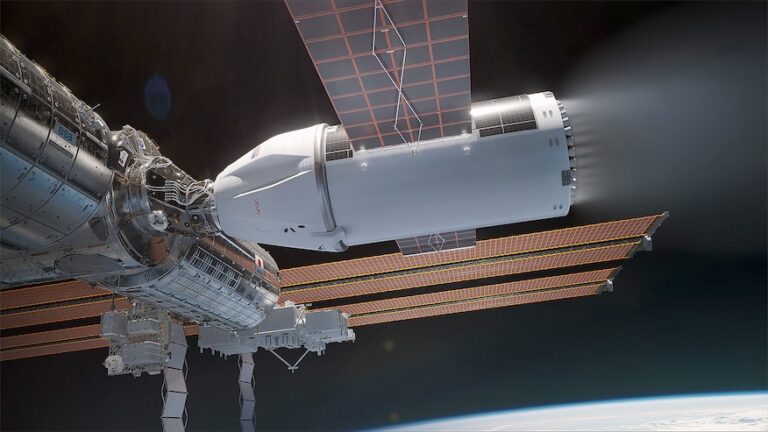

Some reboost functions are being performed by a SpaceX Cargo Dragon vehicle outfitted with a special boost kit in its unpressurized trunk. A NASA spokesperson said that this Dragon, launched to the ISS on the Commercial Resupply Services 33 (CRS-33) mission “will undock in late January 2026, before splashing down and returning critical science and hardware to teams on Earth.”

“Station has sufficient capability for reboost and attitude control, and there are no expected impacts to this capability,” a spokesperson said on Thursday.

M+139: Time lapse of SpaceX CRS-33 Dragon docking to the Node2 Forward Port last week, taken from the window of Crew-11’s Dragon. Nikon Z9 | 15mm | ISO 1000, f/1.8, 1/500s. pic.twitter.com/cfiMAmyeQ0

— Jonny Kim (@JonnyKimUSA) September 16, 2025

As for crew capabilities, it’s unclear how much the Site 31 pad damage will delay the launch of the Soyuz MS-29 mission, if at all. A July 2025 press release from NASA announcing its astronaut, Anil Menon, as a crew member stated that the Soyuz MS-29 mission would launch in June 2026.

However, on Thursday, aspokesperson for the agency said the mission “has always been scheduled to launch in July 2026.”

As for U.S. crewed missions, the SpaceX Crew-12 mission is the next up to bat after NASA confirmed that the next flight of a Boeing CST-100 Starliner spacecraft (Starliner-1) would be a cargo-only mission.

Starliner may carry crew on its next voyage, but that depends on the outcome of the Starliner-1 mission.

Sketching the future

In these final five years, NASA and its partners will begin winding down station operations and in the immediate years before its demise, the station will be slowly lowered using orbital drag and the station’s thrusters over the course of two to two-and-a-half years, according to Dana Weigel, ISS Program Manager, during a post-launch Crew-11 briefing.

“The Russian segment is prime for doing all of that. So, all of the attitude control, debris avoidance, anything we do with actively lowering is from the Russian segment,” Weigel said.

“Once we get down to the point of actually deorbiting, our current plan is to have the Russian segment do attitude control and the USDV do actual thrusting and boost,” she added. “That gives us additional layers of redundancy, so that if something happened with the attitude control, you can then switch over to the USDV. So, it’s very much an integrated plan and an integrated solution.”

One way that delays to future Progress vehicle launches may impact the station is also in stocking up on fuel for those future lowering burns as well as attitude control.

“Part of what Roscosmos is working on right now is fuel delivery. So, we’ve got to get the fuel reserves on station to the point where they can do their portions of this,” Weigel said in early August. “Latest predictions are that will probably be at the right level in early 2028 and we’ll probably start drifting down in mid-2028. We’ve got to make sure we have the fuel there and everyone’s ready to go. And then the USDV will arrive mid-2029.”

As for the crews onboard, assuming the current schedule holds, the final years onboard station may look something like the following:

- Feb. 2026 – SpaceX Crew-12

- July 2026 – Soyuz MS-29

- Oct. 2026 – SpaceX Crew-13 or Starliner-2

- March 2027 – Soyuz MS-30

- June 2027 – Dragon or Starliner

- Nov. 2027 – Soyuz MS-31

- Feb. 2028 – Dragon or Starliner

- July 2028 – Soyuz MS-32

- Oct. 2028 – Dragon or Starliner

- March 2029 – Soyuz MS-33

- June 2029 – Dragon or Starliner

- Nov. 2029 – Soyuz MS-34

- Feb. 2030 – Dragon or Starliner

Asked whether NASA would want its final crew onboard station to be comprised of seasoned veterans instead of making sure its newest astronauts get flight experience Weigel told Spaceflight Now following the Crew-11 briefing that it’s a complicated question.

“I think there are so many different factors that can work on that. One of the things from a medical consideration standpoint is we do limit radiation exposure for crew members and if we’re asking for a year-long mission, we have to factor all of that in for crew health,” Weigel said.

“So, in an ideal sense, you’d say, ‘Yeah, send me somebody who’s flown, who’s great at spacewalks, this, that and the other.’ But too much experience puts you over the radiation limit.”

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly