Now Reading: Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is leaking water like a ‘fire hose running at full blast,’ new study finds

-

01

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is leaking water like a ‘fire hose running at full blast,’ new study finds

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is leaking water like a ‘fire hose running at full blast,’ new study finds

A rocky visitor from beyond our solar system is leaking water like a “fire hose running at full blast,” a new study reports.

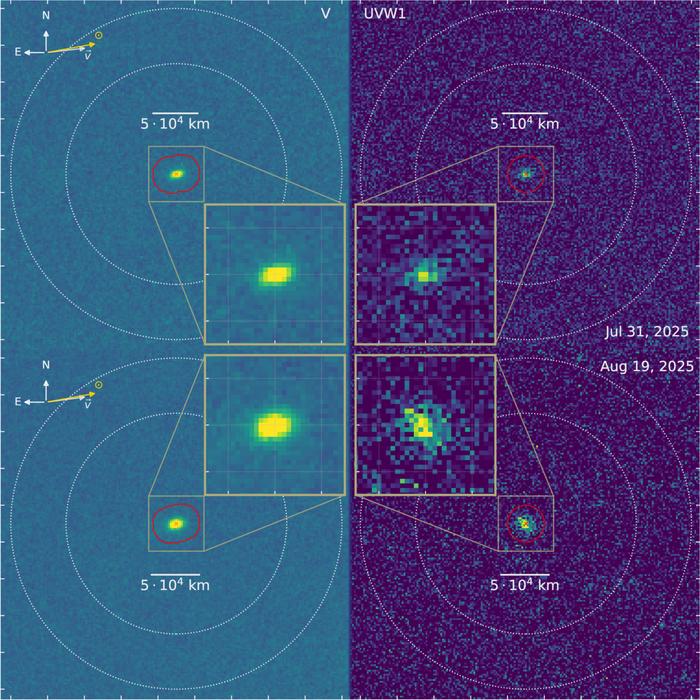

Using NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, scientists have for the first time detected the chemical fingerprint of water spilling from interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, only the third known object from another star system ever observed passing through our cosmic neighborhood.

Water is the universal yardstick of comet science, the baseline for measuring how sunlight drives a comet’s activity and releases other gases. Detecting it in an interstellar visitor allows astronomers to compare 3I/ATLAS directly with comets native to our solar system, offering a rare glimpse into the chemistry of distant planetary systems.

“When we detect water — or even its faint ultraviolet echo, OH — from an interstellar comet, we’re reading a note from another planetary system,” study co-author Dennis Bodewits, a professor of physics at Auburn University, said in a statement. “It tells us that the ingredients for life’s chemistry are not unique to our own.”

‘At a distance where we didn’t expect it’

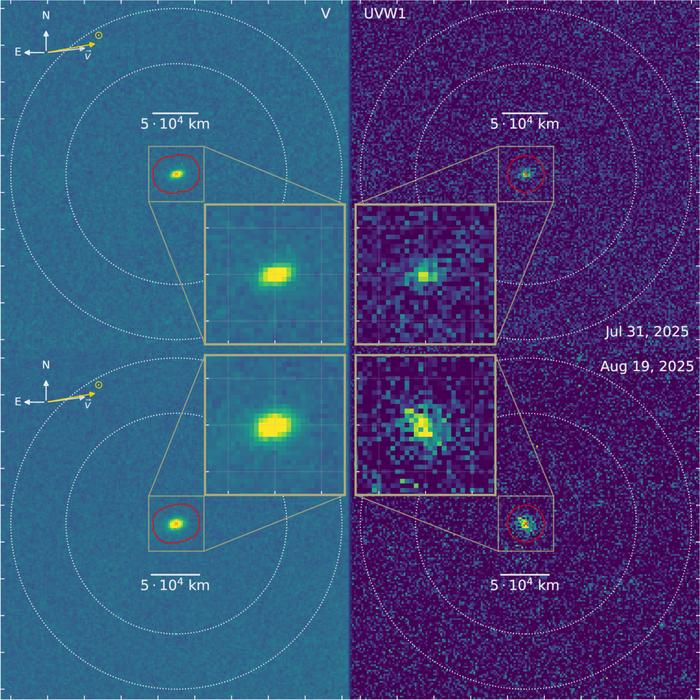

Using the Swift telescope, Bodewits and his team observed 3I/ATLAS in July and August 2025, when it was about 2.9 times farther from the sun than Earth — well beyond the region where water ice typically vaporizes.

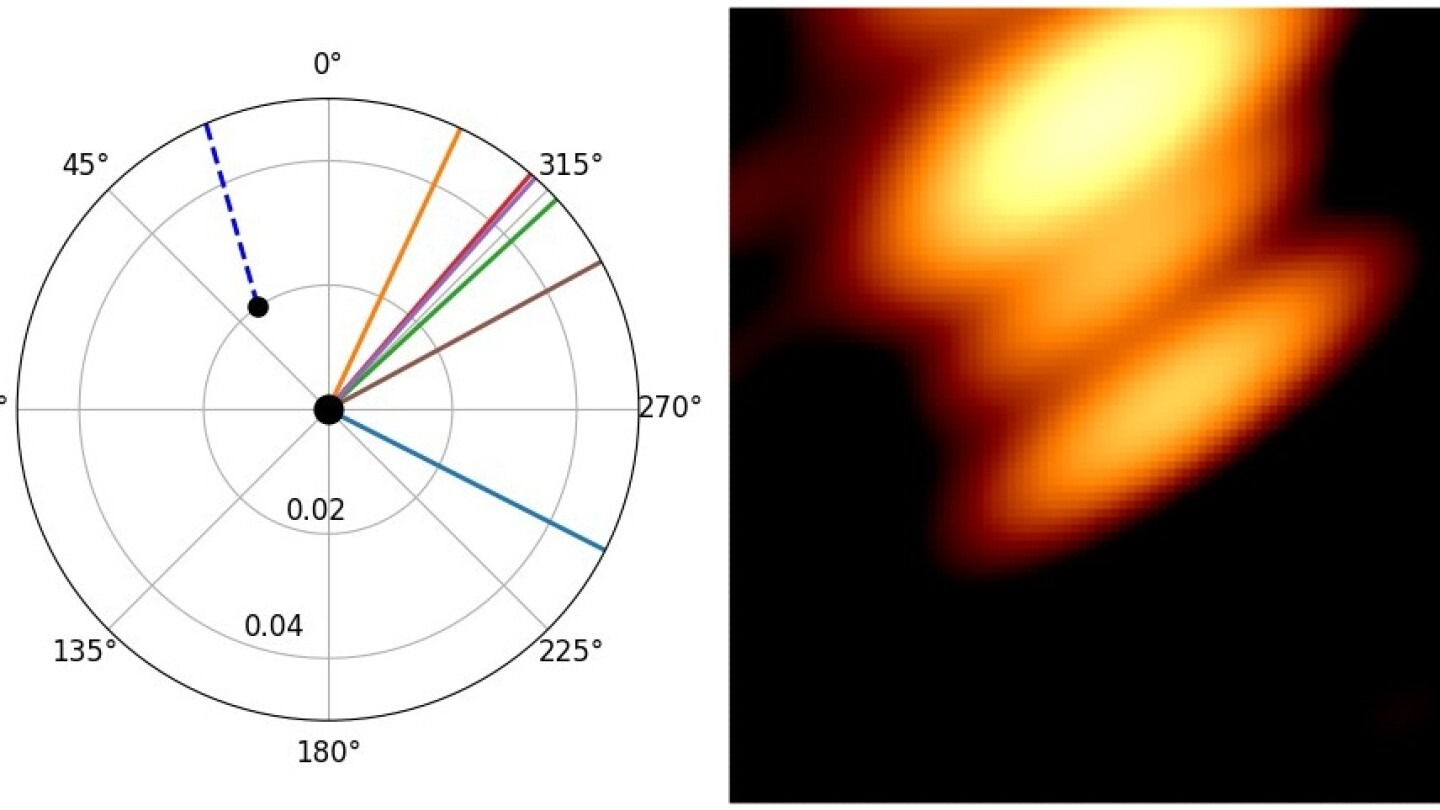

From this distance, Swift detected the faint ultraviolet glow of hydroxyl (OH), the product of water molecules broken apart by sunlight, the study reports. To tease out the delicate signal, astronomers stacked dozens of short, three-minute exposures, combining more than two hours of ultraviolet observations and 40 minutes in visible light.

The result, detailed in a paper published Sept. 30 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, showed that 3I/ATLAS was losing water at a rate of roughly 40 kilograms per second, or “roughly the output of a fire hose running at full blast.”

Based on that outflow rate, the team estimates that at least 8% of the comet’s surface must be active, a surprisingly large fraction compared with the 3% to 5% typically seen in comets from our own solar system, the study notes.

That level of activity, the researchers say, may come not from its solid surface, but by icy debris drifting around it. Near-infrared observations from Gemini South and NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility hint at chunks of ice floating in the coma, the cloud of gas and dust surrounding the nucleus. Once exposed to sunlight, these clumps are warmed up and act like miniature steam vents in space, releasing water vapor even though the comet itself remains too cold for its surface ice to sublimate directly, the researchers say.

“Every interstellar comet so far has been a surprise,” Zexi Xing, a postdoctoral researcher at Auburn University in Alabama who led the new study, said in the same statement. “‘Oumuamua was dry, Borisov was rich in carbon monoxide, and now ATLAS is giving up water at a distance where we didn’t expect it. Each one is rewriting what we thought we knew about how planets and comets form around stars.”

3I/ATLAS has since faded from Swift’s view, but was spotted again in early October by the European Space Agency’s Mars orbiters as it passed about 30 million kilometers from Mars. The agency said it will continue following the interstellar visitor; in November, it plans to turn its Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) toward 3I/ATLAS.

JUICE will observe the comet just after its closest approach to the sun, when it’s expected to be at its most active, and is likely to have the best view of this action, the agency said.

Because JUICE is currently positioned on the far side of the sun and sending data through a slower backup antenna, scientists don’t expect to receive its comet observations until February 2026.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

03Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

04Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits