Now Reading: Is a surprisingly massive exomoon orbiting this big exoplanet?

-

01

Is a surprisingly massive exomoon orbiting this big exoplanet?

Is a surprisingly massive exomoon orbiting this big exoplanet?

EarthSky’s 2026 lunar calendar is available now. Get yours today! Makes a great gift.

- Do exoplanets have exomoons? There are a growing number of candidates, but no distant planet has yet been confirmed to have an orbiting moon.

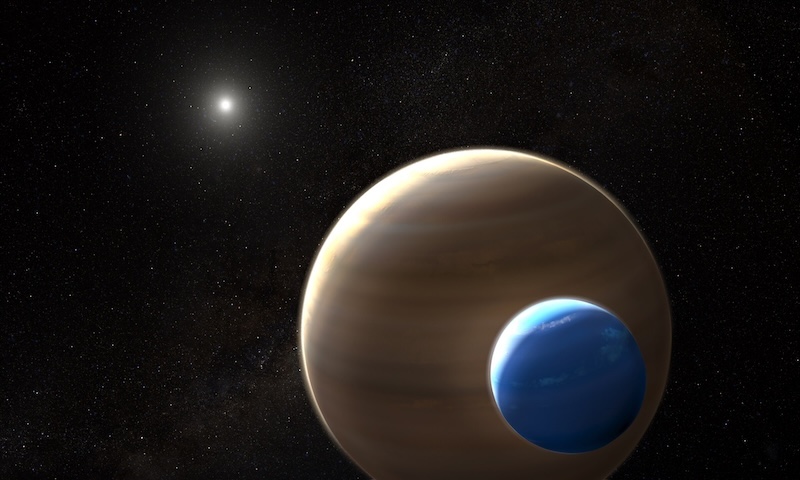

- A gas giant exoplanet 133 light-years away – HD 206893 B – might have a huge exomoon, a team of astronomers says.

- The possible exomoon has a mass 40% that of Jupiter, or nine times the mass of Neptune. It still needs to be confirmed, however.

A massive exomoon 133 light-years away?

We know that there are many exoplanets out there orbiting distant stars. Current models and observational data suggest between 100 billion and 400 billion exoplanets in our Milky Way galaxy. But what about exomoons? On January 29, 2026, a team of astronomers said they’ve detected another potential exomoon. And this one is big. The planet, HD 206893 B, is a gas giant about 28 times as massive as Jupiter, 133 light-years away. The suspected moon is about 40% the mass of Jupiter, or nine times the mass of Neptune.

If the discovery is confirmed, and the size estimate proves correct, we’ll have found an exomoon far larger and more massive than Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, the largest moon in our solar system.

For now, this discovery is one of a small but growing number of candidate exomoons. No exomoon has been confirmed yet. The new work comes from astronomers using the GRAVITY instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in the Atacama desert in Chile. The researchers found the suspected moon by measuring “wobbles” in the motion of its planet.

Robert Lea wrote about the potentially exciting discovery at Space.com on January 22, 2026.

The researchers’ new paper has been accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics, and is available as a preprint on arXiv (November 25, 2025).

Wobbling exoplanet

The researchers examined the orbit of HD 206893 B. They found that the planet exhibited a small “wobble” as it orbited its star. As lead author Quentin Kral at the University of Cambridge in the U.K. and the Paris Observatory mentioned to Space.com:

What we found is that HD 206893 B doesn’t just follow a smooth orbit around its star. On top of that motion, it shows a small but measurable back-and-forth ‘wobble.’ The wobble has a period of about nine months and a size comparable to the Earth–moon distance. This kind of signal is exactly what you would expect if the object were being tugged by an unseen companion, such as a large moon, making this system a particularly intriguing candidate for hosting an exomoon.

Cool discovery! If the exomoon interpretation is right, this object is enormous ! It orbits HD 206893 B at ~0.22 AU on a highly tilted orbit (~60°), blurring the line between a giant exomoon and a low-mass companion. Frontier science in action. observatoiredeparis.psl.eu/un-signal-in…

— Franck Marchis (@allplanets.bsky.social) 2026-01-29T20:41:14.643Z

Hints of a massive exomoon from GRAVITY

The researchers used the GRAVITY instrument on the Very Large Telescope to make the detection. GRAVITY measures the positions of stars and other objects in space using astrometry. Astrometry makes precise measurements of the positions and movements of stars and other celestial bodies. As Kral explained:

This technique has previously been used to measure the long, slow orbits of massive exoplanets and brown dwarfs, where observations spaced years apart are sufficient. In our study, we pushed this approach much further by monitoring the object over much shorter timescales, from days to months. What we found is that HD 206893 B doesn’t just follow a smooth orbit around its star. On top of that motion, it shows a small but measurable back-and-forth ‘wobble.’

Exomoons are difficult to detect because they produce signals that are extremely small compared to those of planets, and those signals depend very strongly on both the observing technique and the system’s geometry.

Transit method vs astrometry

Astronomers have used the transit method to detect many exoplanets. That’s when a planet transits – passes in front of – its star as seen from Earth. It’s not as useful for finding exomoons, however. Technically, it can find them, but is more suitable for planets that orbit very close to their stars. And those planets are the least likely to have moons. Kral said:

The transit method which has been the most successful technique for finding exoplanets can, in principle, detect moons comparable in size to Jupiter’s largest moons. However, it is most sensitive to planets orbiting very close to their stars, and theoretical studies suggest that such close-in planets are unlikely to retain large moons over long periods of time.

Astrometry is better suited for detecting exomoons around planets farther from their stars. As Kral explained:

Astrometry, the technique we use, is sensitive to longer-period moons orbiting planets or substellar companions far from their stars. This makes it particularly promising for detecting exomoons in regions where they are expected to be stable, at least for the most massive moons, which are likely to be the first ones we can find.

Questioning the definition of ‘moon’

The results of GRAVITY’s measurements suggest something amazing. HD 206893 B has a moon. But this moon is huge! If real, it is about 40% the mass of Jupiter. That’s nine times the mass of Neptune: a moon the size of some of the larger planets in our solar system. It orbits its planet about once every nine months at about 0.22 astronomical units, or 1/5 the distance between Earth and the sun. In addition, its orbit is tilted around 60 degrees to the orbital plane of the planet.

If confirmed, such a giant moon could call into question our current definition of what a moon is. Is this a moon and planet, or a double planet system?

Comparison to Ganymede

The largest and most massive moon in our solar system is Ganymede, a moon of Jupiter. At 3,270 miles (5,260 kilometers) in diameter, it is larger than both Mercury and Pluto. But it pales in comparison to the possible moon of HD 206893 B. The potential exomoon would be about nine times the mass of Neptune, and Ganymede is thousands of times less massive than Neptune. Kral said at Space.com:

In our solar system, the most massive moon is Ganymede, which is still extremely small compared to what we are inferring here. Ganymede is thousands of times less massive than Neptune, so there is an enormous gap in mass between the largest moons we know and this potential exomoon candidate.

This naturally raises the question of whether such an object should even be called a moon. At these masses, the distinction between a massive moon and a very low-mass companion becomes blurred. However, there is currently no official definition of an exomoon, and in practice, astronomers generally refer to any object orbiting a planet or substellar companion as a moon.

We will find exomoons

Kral is optimistic about being able to confirm exomoons:

It’s important to keep in mind that we are likely only seeing the tip of the iceberg. Just as the first exoplanets discovered were the most massive ones orbiting very close to their stars – simply because they were the easiest to detect – the first exomoons we identify are expected to be the most massive and extreme examples.

As observational techniques improve, our definitions and understanding of what constitutes a moon will almost certainly evolve.

Bottom line: Astronomers using the Very Large Telescope might have found a massive exomoon – 40% the mass of Jupiter – orbiting a giant exoplanet 133 light-years away.

Source: Exomoon search with VLTI/GRAVITY around the substellar companion HD 206893 B

Read more: Astronomers discover 6 possible new exomoons

Read more: New possible volcanic exomoon orbiting searing hot exoplanet

The post Is a surprisingly massive exomoon orbiting this big exoplanet? first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly