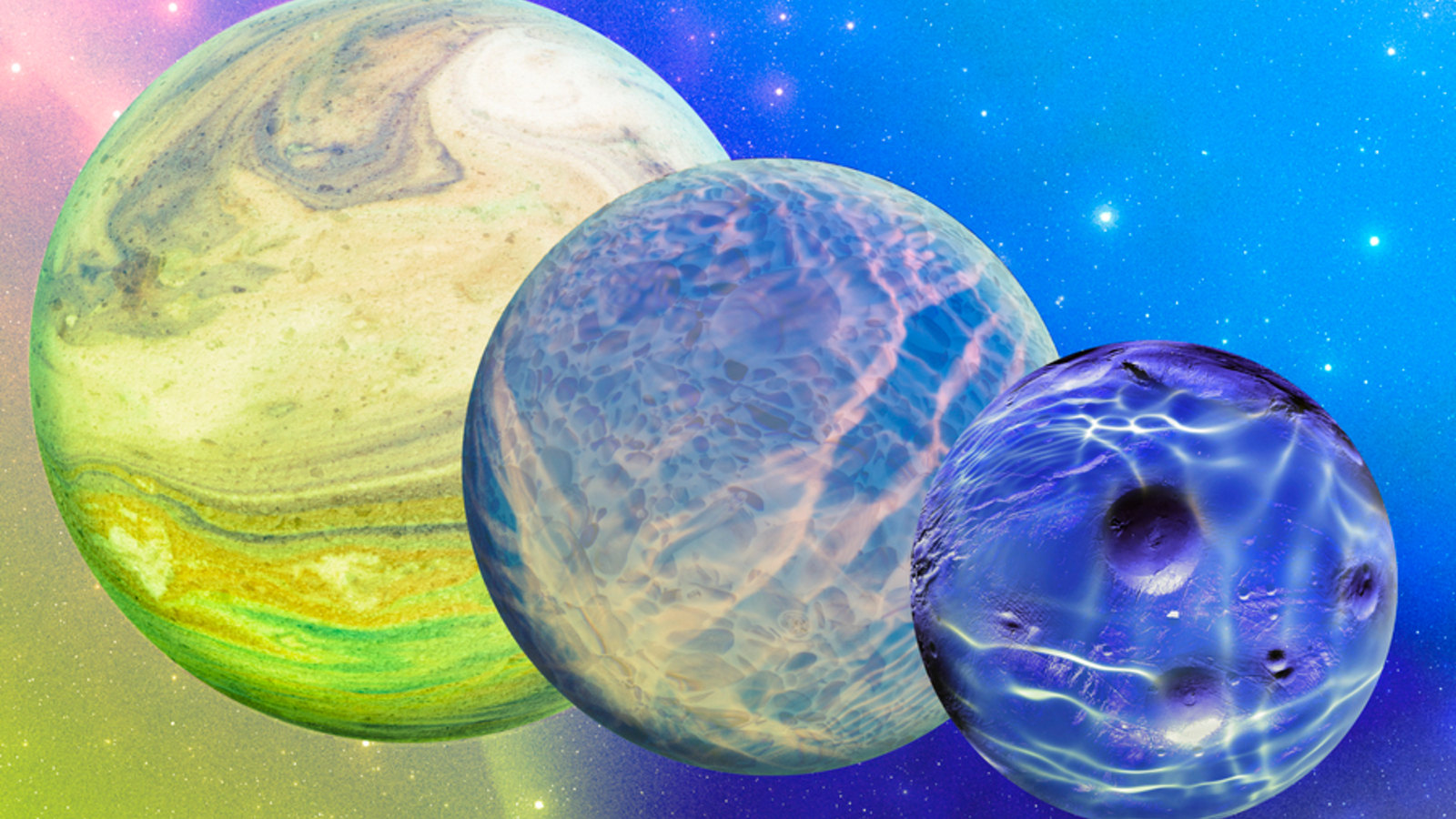

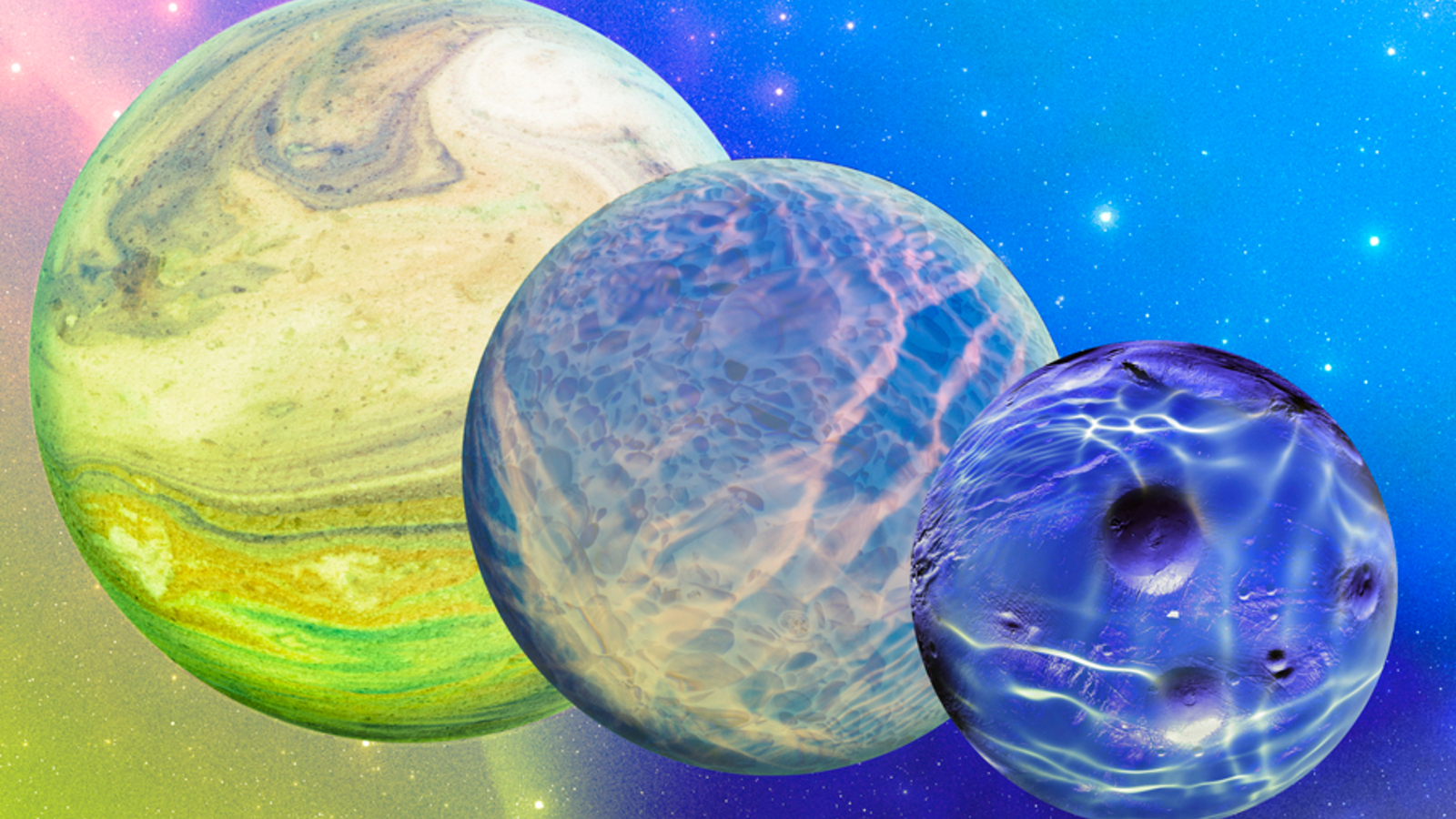

Now Reading: Is water really a necessary ingredient for life? Aliens may swim in truly exotic pools

-

01

Is water really a necessary ingredient for life? Aliens may swim in truly exotic pools

Is water really a necessary ingredient for life? Aliens may swim in truly exotic pools

Here on Earth, liquid water is key to life. But elsewhere? That might not be the case. A new study suggests that other liquids might be able to support life on worlds beyond our own.

“We consider water to be required for life because that is what’s needed for Earth life. But if we look at a more general definition, we see that what we need is a liquid in which metabolism for life can take place,” study leader Rachana Agrawal, a postdoctoral student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), said in a statement.

Agrawal and her team studied ionic liquids — salts that are liquid at sub-boiling temperatures (below 212 degrees Fahrenheit, or 100 degrees Celsius) — as a potential hospitable environment for life. Per the researchers’ laboratory experiments, ionic liquids can likely form from ingredients found on rocky planets and moons.

Most importantly, the team determined that ionic liquids could form where liquid water can’t, thanks to its ability to remain liquid at a wide range of temperatures and pressures. And ultimately, these ionic liquids might be able to support biomolecules like proteins.

“[T]his can dramatically increase the habitability zone for all rocky worlds,” said Agrawal.

As things go in science, this discovery was something of a happy accident. Initially, the team set out to investigate signs of life on Venus, looking to find a way to collect and evaporate sulfuric acid from Venus’ clouds. But when the researchers ran their evaporation experiments, they found that a liquid layer always remained. That layer, they determined, was an ionic liquid, formed when sulfuric acid reacted with glycine.

Related Stories:

“From there, we took the leap of imagination of what this could mean,” said Agrawal. “Sulfuric acid is found on Earth from volcanoes, and organic compounds have been found on asteroids and other planetary bodies. So, this led us to wonder if ionic liquids could potentially form and exist naturally on exoplanets.”

More study is necessary, of course. “We just opened up a Pandora’s box of new research,” said MIT professor Sara Seager, a co-author of the study. “It’s been a real journey.”

The team’s paper was published Monday (Aug. 11) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly