Now Reading: Janus Henderson invests in Starlab Space

-

01

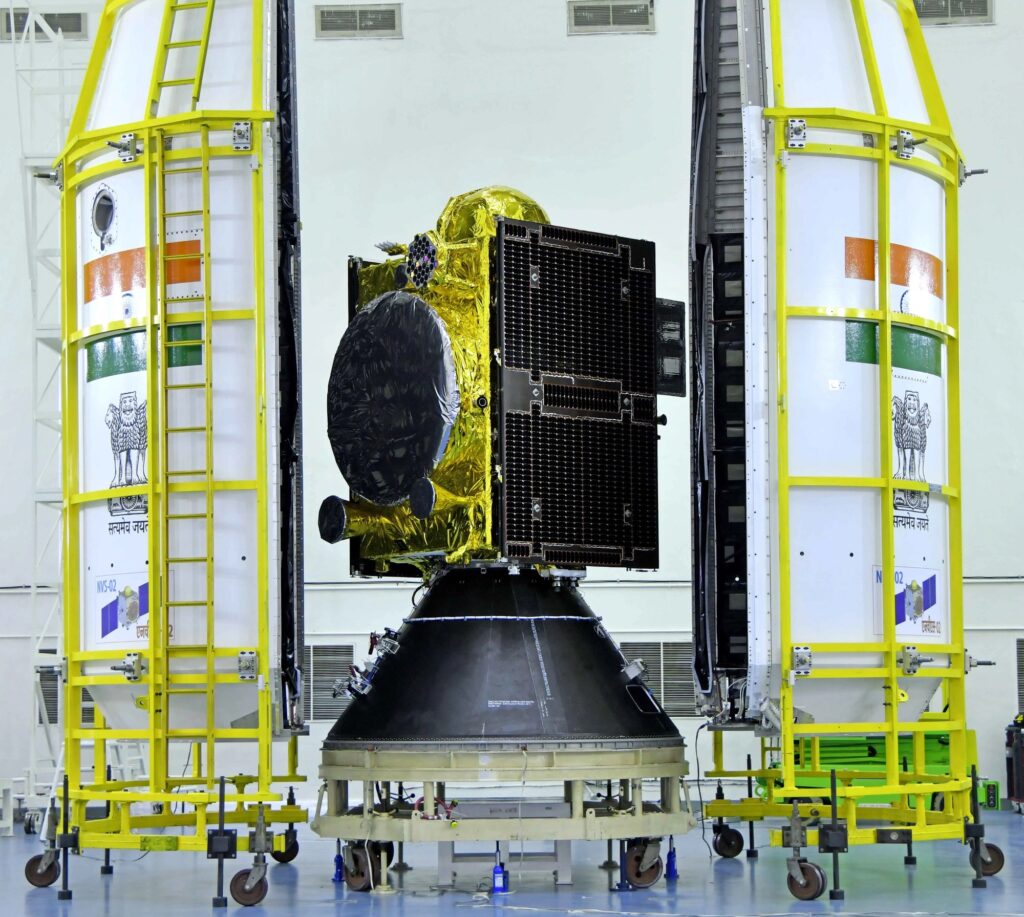

Janus Henderson invests in Starlab Space

Janus Henderson invests in Starlab Space

MUNICH — Starlab Space has secured funding from an investment group as development of its proposed commercial space station reaches a critical phase.

Janus Henderson Group, a London-based asset management company, announced Nov. 20 that it invested in Starlab Space, the joint venture developing a commercial station. It did not disclose the size of the investment, and a Janus Henderson spokesperson declined to comment.

Starlab is one of several companies working on commercial space stations. It is part of the first phase of NASA’s Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations, or CLD, program, which supports companies as NASA plans to retire the International Space Station and transition research to commercial successors.

“We have strong conviction that Starlab has the best design, lowest cost profile and most compelling business model of any of the contenders vying to replace the ISS after its deorbit in 2030,” Jonathan Coleman, small-cap growth portfolio manager at Janus Henderson, said in a statement. “The U.S.-led global partnership is a distinctive model that makes the business a more attractive partner to NASA and international space agencies.”

“The investment from a global financial leader such as Janus Henderson is a strong market signal that the commercial space economy is entering a new phase of maturity,” Dylan Taylor, chairman and chief executive of Voyager Technologies, said in the statement. Voyager is the lead company in the Starlab Space joint venture.

The joint venture also includes Airbus Defence and Space, Mitsubishi, MDA Space, Palantir and Space Application Services as investors, along with strategic partners that range from Northrop Grumman to Hilton. Janus Henderson noted it is an investor in “multiple strategic backers” of Starlab but did not identify them.

The investment is one of several recent developments for Starlab. The company announced Nov. 5 it selected Leidos to handle assembly, integration and testing of the station, after announcing in September that Vivace would build the primary structure of the large, single-module station. Space Application Services, a Belgian company that provides payload integration and operations services, joined the joint venture in September with an undisclosed investment.

Marshall Smith, chief executive of Starlab Space, said at a Nov. 3 event at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center that the company expects to begin the station’s critical design review in December, with some hardware already in production.

He said 55% of the station’s payload space is already reserved. “The market is really in the things that have been tested and we know work in space: for example, biopharma, cancer drugs,” he said, as well as microgravity manufacturing.

One uncertainty is NASA’s approach to the next phase of the CLD program. NASA said in the summer it planned to award multiple Space Act Agreements to fund commercial station development, including a commercial demonstration mission, rather than award a contract to build and certify a station for NASA astronauts.

That approach also suggested NASA is moving away from a continuous human presence — sometimes called “continuous heartbeat” — in favor of missions that could last as little as 30 days. NASA released a draft solicitation in September for the next CLD phase, but the six-week government shutdown delayed the release of the final version.

Shifting to short-duration missions instead of continuous presence would affect the kind of work possible on commercial stations, Smith said, because many activities require human interaction, as well as the supply chain for services like cargo transportation to support those stations.

“I think a gap would be very hard on the market,” he said. “I don’t think there needs to be a gap. We let companies decide what they want to build based on commercial markets.”

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly