Now Reading: Laying the foundation for America’s space future

-

01

Laying the foundation for America’s space future

Laying the foundation for America’s space future

There really is no terrestrial parallel to space exploration. While American pioneers pushed westward with minimal government oversight, the space age began with government funds and directives. Today, what was once the domain of nation-states is now (theoretically) accessible to upstarts and dreamers.

While the United States and peer nations maintain government-directed space programs, the most promising new technologies are emerging from private industry. The promise of the “space economy” is becoming reality. Reusable rocket technology is driving launch costs lower even in the face of regulatory hurdles.

Federal Communications Commission Chairman Brendan Carr took a step to help America’s regulatory infrastructure match the pace of its commercial industry, when he announced on Oct. 6 that the FCC would create a “licensing assembly line” for satellite launches and drive more efficient use of satellite spectrum. These are meaningful steps toward unleashing American innovation and developing an enduring orbital economy. And it should serve as a template for every federal agency with jurisdiction over space operations.

Gearing up: the companies fueling this future

Space operations and technologies undergird modern civilization. Communications and GPS-supporting satellites enable billions of people to navigate their world. Satellite broadband is bringing far-flung corners of the Earth online. In-space assembly and manufacturing promises to support future orbital operations while delivering breakthrough innovations for Americans here on the ground.

Chairman Carr made the aforesaid remarks during the ribbon cutting of Apex’s Factory One, a new building that will enable the company to mass-produce up to 50 standardized satellite buses a year. Joining Apex CEO Ian Cinnamon were representatives from Northwood space, a company building mass-produced ground stations using phased array technology that can connect to up to 10 satellites simultaneously, and Varda, a company pursuing microgravity-assisted biomedical research in orbit and reentry.

Apex, Varda and Northwood are all part of a larger ecosystem manifesting in El Segundo and across Southern California. Companies are taking advantage of falling launch costs, increasingly capable software systems and the reality that an orbital economy driven by private actors, rather than solely government interests, is here.

Regulatory countdown: clearing the path to orbit

Unfortunately our best and brightest private companies are routinely suffocated as they try to navigate America’s space regulatory framework.

For starters, American space regulation is fragmented across multiple federal agencies. Beyond NASA, three other federal agencies wield regulatory authority over aspects of spaceflight and in-orbit activities. Each agency operates with its own timelines, requirements and approval processes.

In prior eras of space exploration, missions were infrequent because of limited vehicle and launch capabilities. This allowed the few firms involved, along with their government partners, to absorb escalating regulatory costs through patience and deep pockets. Today’s crop of space entrepreneurs operate under different constraints. Regulatory delays measured in months — or years — are fatal to startups racing to validate technologies and capture market share.

The stakes extend beyond individual companies. China launched more than 60 orbital missions in 2024 and is rapidly expanding its commercial space sector with significant government backing. Europe is streamlining regulations in hopes of competing in this new era of space competition. Meanwhile, American companies — with superior technology and deeper capital markets — face months of delays while foreign competitors move at startup speed. We are handing our adversaries an advantage they don’t deserve and couldn’t otherwise earn.

Since assuming leadership, Carr has emphasized making the U.S. “the most friendly regulatory environment in the world” for space operations. The FCC has already cut its satellite application backlog in half since January 2025 and implemented reforms including 30-day review periods for earth station renewals.

Carr announced October would be “Space Month” at the FCC, kicking off two regulatory proceedings that could significantly accelerate U.S. satellite launches and space activities writ large. The first will remodel the existing satellite launch licensing process to limit time spent in review and create clear standards and timelines for applicants. The second will focus on encouraging more intensive use of satellite spectrum, specifically the upper microwave band, and reform Earth Station siting rules. Such reforms advance American space operations by optimizing government regulatory review, incentivizing efficient use of resources and setting clear rules so American companies can compete on the merits of their products rather than their legal teams.

These reforms should be the standard, not the exception. Every federal agency with space jurisdiction should be asking the same questions Carr is asking: “Does this regulation serve current technological realities?” “Does this timeline match the pace of innovation?” “Are we enabling American competitiveness or constraining it?”

The goal isn’t to eliminate oversight or compromise safety. It’s to ensure that approval processes match the cadence of modern technology development. A satellite constellation designed in 2023 that’s still waiting for licensing approval in 2025 isn’t just delayed — it’s destined for obsolescence. The technology will be surpassed, the market opportunity will evaporate and the American company that designed it will fall behind foreign competitors who faced no such barriers.

The path forward

The announcement signals an understanding that space regulation must evolve as rapidly as the industry it oversees. Streamlined licensing, faster approvals and regulatory clarity are prerequisites for American competitiveness. The infrastructure and systems being built today will define America’s position in space for decades to come. But infrastructure alone won’t secure that position. The regulatory environment must match the ambition and speed of American entrepreneurs.

The choice facing policymakers is stark: adapt our regulatory systems to the pace of innovation, or watch the space economy of the 21st century get built elsewhere.

The companies are ready. The technology is proven. The capital is available. The only question is whether Washington will clear the path or continue placing obstacles in it.

Joshua Levine is a research fellow at the Foundation for American Innovation

Prineha Narang is an American scientist, engineer and entrepreneur. She is a professor at UCLA, Operating Partner at DCVC, and a non-resident fellow at the Foundation for American Innovation.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

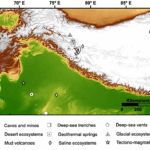

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

03Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

06Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly -

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits

07Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits