Now Reading: Life on Venus? Exciting new VERVE mission could find it

-

01

Life on Venus? Exciting new VERVE mission could find it

Life on Venus? Exciting new VERVE mission could find it

- Could there be microbes living in Venus’ clouds? A new proposed mission concept from researchers in the U.K. called VERVE might answer that question.

- VERVE, a small probe, would analyze Venus’ atmosphere and search for possible biosignature gases like phosphine and ammonia.

- The probe would hitch a ride on the EnVision mission spacecraft, scheduled to launch sometime in 2031.

Is there life on Venus?

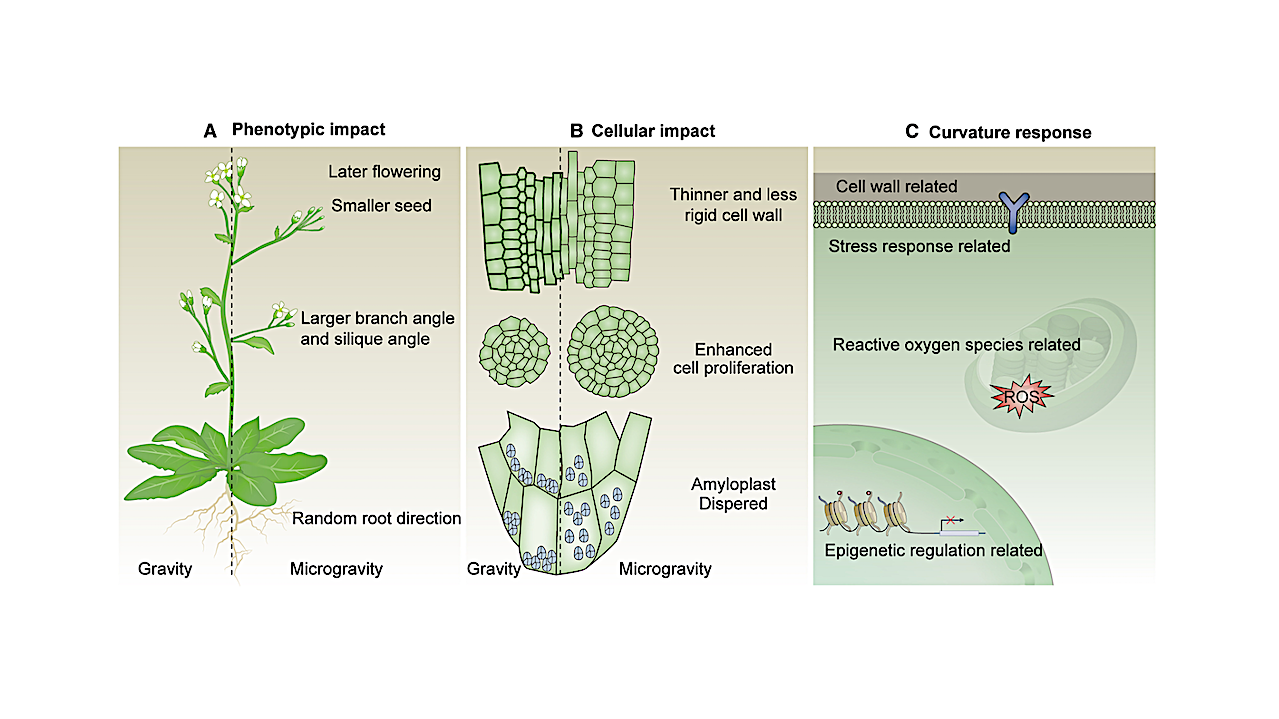

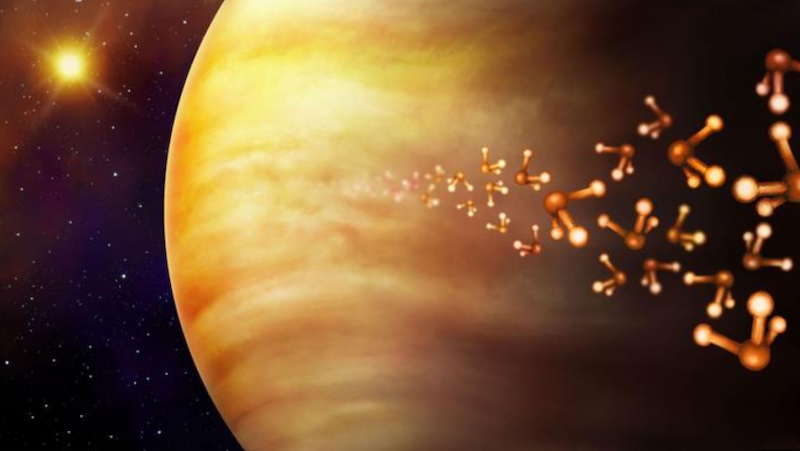

Is there life in the clouds of Venus? We still don’t know for sure, although some studies continue to support this possibility. Now, scientists in the U.K. – led by astronomer Jane Greaves at Cardiff University – have proposed a new mission that could finally answer the question. The researchers said on July 9, 2025, that a CubeSat-sized probe called VERVE (Venus Explorer for Reduced Vapours in the Environment) could be added to the European Space Agency’s EnVision mission, currently scheduled to launch in 2031. When it arrives at Venus, VERVE would detach from EnVision and begin its own survey of the planet’s dense atmosphere. It would search for and map phosphine, ammonia and other gases rich in hydrogen. These gases might be biosignatures, or signs of microbial life.

The researchers presented the details about the new mission concept at the Royal Astronomical Society’s National Astronomy Meeting 2025 in Durham, U.K. on July 9, 2025.

The EnVision mission will study Venus’ surface, interior and atmosphere. Although the planet’s surface is scorching hot, too hot for life as we know it, the middle layers of the atmosphere – about 31 miles (50 km) up – are much more Earth-like in pressure and temperature, around 85 Fahrenheit (30 C) to 158 Fahrenheit (70 C).

Could microbes inhabit that environment, as they do on Earth?

Hitching a ride to Venus

If the mission is approved, VERVE – a small CubeSat-sized probe – would hitch a ride to Venus with the EnVision spacecraft. Upon arrival at Venus, it would detach from EnVision and enter a high orbit. Then, it would begin its own study of Venus’ atmosphere.

EnVision, meanwhile, would continue its own mission of exploring the planet overall. VERVE currently has an estimated budget of 50 million euros (43 million pounds).

There's been plenty of debate about the possibility of life on Venus, ever since phosphine was detected in the planet's clouds in 2020 and hints of another potential biomarker ammonia last year.??

— Royal Astronomical Society (@royalastrosoc.bsky.social) 2025-07-09T16:55:25.848Z

But the only way to know for sure whether "extremophile" microbes might be responsible for producing these gases is to go there, researchers behind the JCMT-Venus project say, and that's what they're proposing to do…ras.ac.uk/news-and-pre… #NAM2025

— Royal Astronomical Society (@royalastrosoc.bsky.social) 2025-07-09T16:55:26.616Z

2 potential biosignatures

The VERVE mission concept is based on findings in recent years about Venus’ atmosphere. This is the discovery of evidence for the gases phosphine and ammonia. Greaves and her colleagues announced the still-debated phosphine discovery in late 2020, and another team of scientists announced the tentative finding of ammonia in 2024.

Both of those gases are unexpected in the atmosphere of a planet like Venus. As Greaves noted in the abstract for the National Astronomy Meeting presentation:

Ground-based observations are starting to uncover reduced gases that are very unexpected in the oxidised atmosphere of Venus. Their presence suggests a redox disequilibrium, with one possible contributor being the presence of anaerobic microorganisms. We are proposing a mission to the ESA mini-Fast call to study these gases up close, hoping for a ride to Venus alongside ESA EnVision in 2031. I will discuss the plan for VERVE – the Venus Explorer for Reduced Gases in the Environment – including its instrument and science plan and the relation to other missions including the Venus Morning Star life-seeking mission.

Where do the phosphine and ammonia come from?

Confirming – or not – the gases is one thing. But determining their origin is another. Are they biological or non-biological? Greaves said:

Our latest data has found more evidence of ammonia on Venus, with the potential for it to exist in the habitable parts of the planet’s clouds. There are no known chemical processes for the production of either ammonia or phosphine, so the only way to know for sure what is responsible for them is to go there. The hope is that we can establish whether the gases are abundant or in trace amounts, and whether their source is on the planetary surface, for example in the form of volcanic ejecta. Or whether there is something in the atmosphere, potentially microbes that are producing ammonia to neutralise the acid in the Venusian clouds.

The more recent tentative detection of ammonia is just as interesting as the phosphine. On Earth, it is primarily the result of the decay of plant and animal matter. Smaller amounts also come from natural processes such as volcanic activity. It can also form on planets like Jupiter, thought to be primarily through intense thunderstorms and ammonia-water “mushballs.”

But planets like Jupiter, and their atmospheres, are a lot different from rocky worlds like Venus and Earth. So the source of Venus’ ammonia is still a puzzle. Some scientists theorize that both the ammonia and phosphine could come from volcanoes. And indeed, there is growing evidence for active volcanoes on Venus. But other scientists have said they likely wouldn’t produce enough to match the levels reported.

Conflicting studies

The phosphine in particular has been the subject of debate and controversy. After the initial announcement in 2020, some other studies of Venus’ atmosphere failed to confirm it. But then even more recent studies from Greaves and her colleagues – for the long-term JCMT-Venus project – did find it again, along with more clues. The team found that the gas seems to follow the planet’s day-night cycle and also varies with time and location. In the day-night cycle, sunlight destroys the phosphine, but then it still gets replenished somehow. Dave Clements, at Imperial College London, is the leader of the JCMT-Venus project. He said:

This may explain some of the apparently contradictory studies and is not a surprise given that many other chemical species, like sulphur dioxide and water, have varying abundances, and may eventually give us clues to how phosphine is produced.

Bottom line: Could there be life on Venus? A new probe concept from the UK would hitch a ride with the EnVision mission and look for biosignature gases in Venus’ atmosphere.

Source: VERVE – a proposal for an ESA mini-Fast mission to Venus

Via Royal Astronomical Society

Read more: Amino acids on Venus? New study says it’s possible

Read more: Venus’ clouds could soon be brought to Earth

The post Life on Venus? Exciting new VERVE mission could find it first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly