Now Reading: Live coverage: SpaceX to launch NASA, NOAA missions exploring the impacts of the Sun

-

01

Live coverage: SpaceX to launch NASA, NOAA missions exploring the impacts of the Sun

Live coverage: SpaceX to launch NASA, NOAA missions exploring the impacts of the Sun

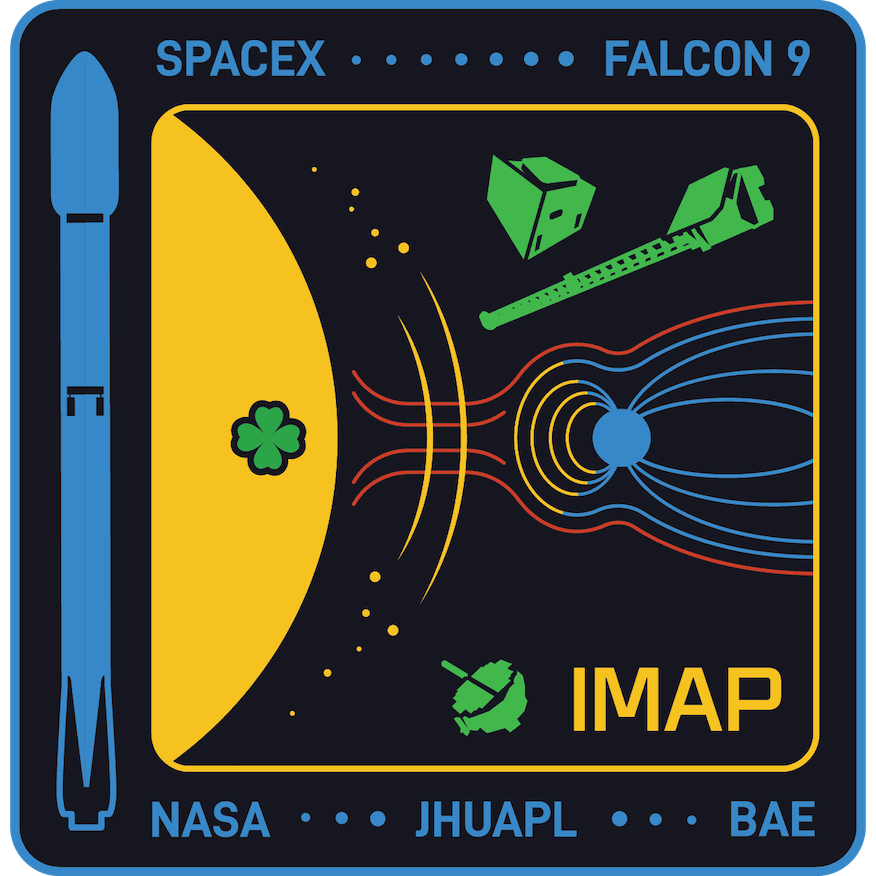

A trio of Sun-studying, marquee missions for both NASA and the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (NOAA) is set to take off on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket shortly after sunrise on Wednesday.

Leading this rideshare missions is NASA’s Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) alongside the agency’s Carruthers Geocorona Observatory and NOAA’s Space Weather Follow-On Lagrange 1 (SWFO-L1).

Liftoff of the Falcon 9 rocket from Launch Complex 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center is set for 7:30 a.m. EDT (1130 UTC).

Spaceflight Now will have live coverage beginning about an hour prior to liftoff.

Heading into Wednesday’s launch opportunity, the 45th Weather Squadron forecast a 90 percent chance for favorable weather. Meteorologists are tracking a low chance for storms to spoil the launch.

“Atlantic showers will linger over the local waters into the Wednesday morning window and there remains a low chance for this activity to drift close enough to coast to be a concern,” launch weather officers wrote. “Some mid and upper level clouds, likely once again anvils from Gulf storms, will be around, but model consensus continues to have this too high to be a concern for Thick Cloud Layers or Anvil Cloud Rules.”

SpaceX will launch the mission using a relatively new Falcon 9 first stage booster: 1096. It’s flying for a second time after launching the KF-01 mission for Amazon’s Project Kuiper satellite constellation in July.

More than 8.5 minutes after liftoff, SpaceX will attempt to land B1096 on the drone ship, Just Read the Instructions. If all goes well, this will be the 137th landing on this vessel and the 510th booster landing to date.

The deployment sequence for the three spacecraft is scheduled to begin about an hour and 23 minutes after liftoff, with roughly seven minutes separating each spacecraft jettison.

NASA said it anticipates acquiring signal from IMAP at about 10 minutes after it’s released, which should be about 9:03 a.m. EDT (1303 UTC). It notes that this is an approximate time.

Acquisition of signal for Carruthers is expected about 30 minutes after that.

Here comes the Sun

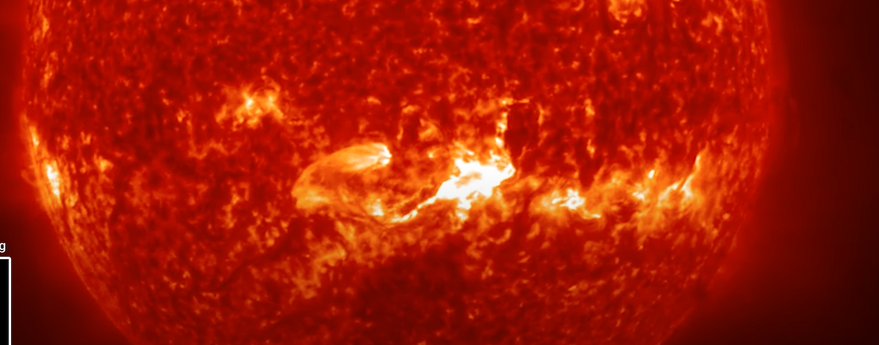

Each of the three mission is focusing on a different aspect of the Sun. Those range from immediate impacts to our planet and the technology we rely on to deep space exploration, like the upcoming Artemis 2 mission, launching no earlier than February 5.

“As humanity expands and explores beyond the Earth, these upcoming missions add these new pieces to the puzzle of our space weather, whether it be within our heliophysics fleet, Parker Solar Probe, the closest thing to the Sun, or the Voyagers that have the farthest expanse out into our heliosphere,” said Joseph Westlake, Director of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate’s Heliophysics Division.

“IMAP covers both of those realms and Carruthers looks back to our home and Earth. This research will support a resilient society that thrives while living with our closest star.”

IMAP features a suite of 10 science instruments and will study the edge of the heliosphere, creating a complete map of the boundary that protects our solar system from a varying amount of galactic radiation.

David McComas, the principal investigator for IMAP, describes the heliosphere as the Sun’s regional influence established by a the outwardly flowing solar wind bound by the outer edge known as the heliopause, which “separates matter that came from the Sun with matter that came from other stars and the outside part of the galaxy.”

IMAP will document both short-term and long-term space weather that can help future space weather predictions.

“We wanted to have two sets of instruments, a set of instruments that measured the ions coming out from the sun, from the solar wind and low energies all the way up through super thermals and energetic particles,” McComas said. “And then they go out, they interact, and some fraction come back as energetic neutral atoms. We wanted to be able to cover this the entire same energy range of those particles coming back, so that we got the full life cycle of the particles. That’s what drove three of each.”

Creating actionable space weather forecasts is the job of NOAA’s SWFO-L1 spacecraft. It’s designed to provide warning of a coronal mass ejection anywhere between 12 hours to a few days before it would reach the Earth.

Once that reaches the spacecraft and it can tell its strength with greater specificity, it can translate that back to mission managers with a 15 to 45 minute warning.

“Unlike the other satellites that are being launched, the IMAP and Caruthers, which are science missions… we are a science application mission,” said Richard Ullman, NOAA Space Weather Operations Director said. “So we are looking at the same phenomena for the application of being prepared for the space weather that’s going to impact us.

“We’re hoping that these, IMAP and Caruthers, will improve our knowledge and make us able to make better forecasts, but what we’re doing here is the operational forecast day to day.”

While IMAP and SWFO-L1 are eyeing the Sun, NASA’s Carruthers Geocorona Observatory will be aiming back at the Earth. It will be far enough away to capture a full picture of the outermost layer of Earth’s atmosphere using a pair of imagers.

Taking continuous pictures of the full geocorona as it’s impacted by solar wind and other space weather events will allow researchers to better understand how this piece of the atmosphere is and isn’t able to protect the Earth.

The spacecraft is named after Dr. George Carruthers, a three-time University of Illinois alumnus and researcher with the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, who proposed and designed the far ultraviolet camera/spectograph that flew to the Moon during the Apollo 16 mission in 1972.

Now, decades later, another University of Illinois researcher, Lara Waldrop, is leading the mission that bears the name of her fellow Illini.

“I referenced his work in the original proposal, not knowing that he was a University of Illinois alum. And this is University of Illinois’ first NASA mission,” Waldrop said. “It’s incredibly exciting, but especially to know that he designed the first ultraviolet imaging system. It’s still on the moon, and here we are about to launch cameras that use his technology, and we’re going to be deploying those into deep space to acquire — he acquired a few images. We’ll be getting a few every hour.”

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors