Now Reading: Magnetic avalanches on the sun reveal the hidden engine powering solar flares

-

01

Magnetic avalanches on the sun reveal the hidden engine powering solar flares

Magnetic avalanches on the sun reveal the hidden engine powering solar flares

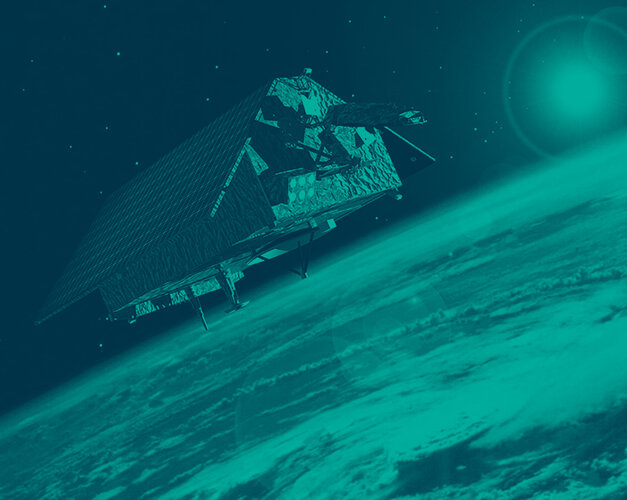

A giant solar flare on our sun was powered by an avalanche of smaller magnetic disturbances, providing the clearest insight yet into how energy from our star is released in a torrent of high-energy ultraviolet light and X-rays. The discovery was made by the European Space Agency (ESA) Solar Orbiter mission, which is imaging the sun from closer than any spacecraft before it.

Some solar flares can result in coronal mass ejections (CMEs) – huge plumes of plasma blown off the sun’s corona and into deep space. If their trajectory away from the sun intersects with Earth‘s location, they can trigger geomagnetic storms that can damage satellites and power grids while disrupting communications, and dazzle us with colorful auroral lights.

The more we learn about how solar flares are triggered, the better prepared we can be to predict when a harmful flare and CME is about to occur. Solar Orbiter’s new observations are a major step towards being able to do this.

“This is one of the most exciting results from Solar Orbiter so far,” Miho Janvier, who is the ESA co-Project Scientist on Solar Orbiter, said in a statement. “Solar Orbiter’s observations unveil the central engine of a flare and emphasize the crucial role of an avalanche-like magnetic energy release mechanism at work.”

Getting to the bottom of solar flares

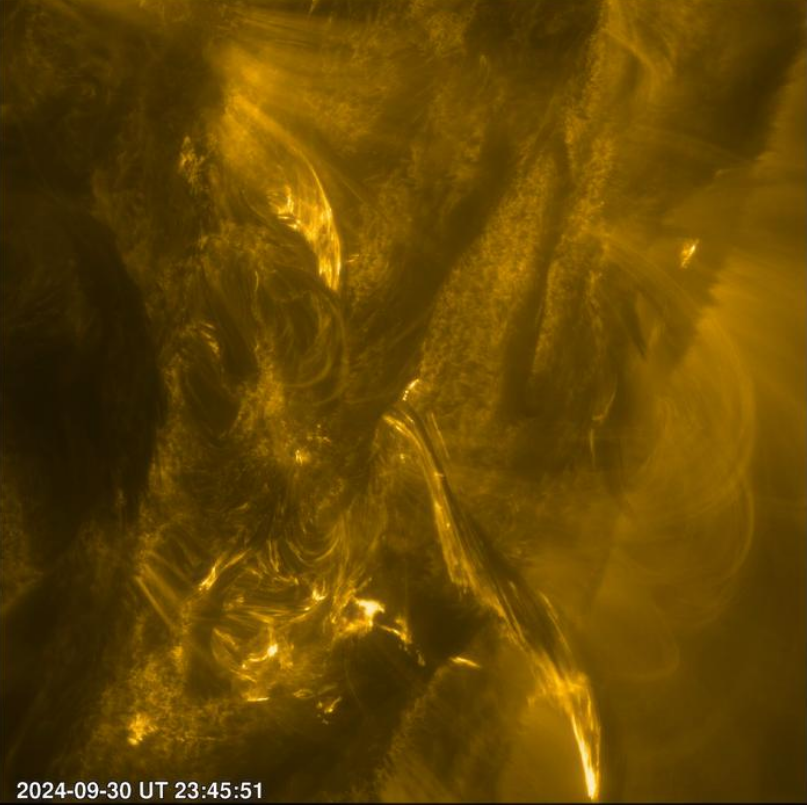

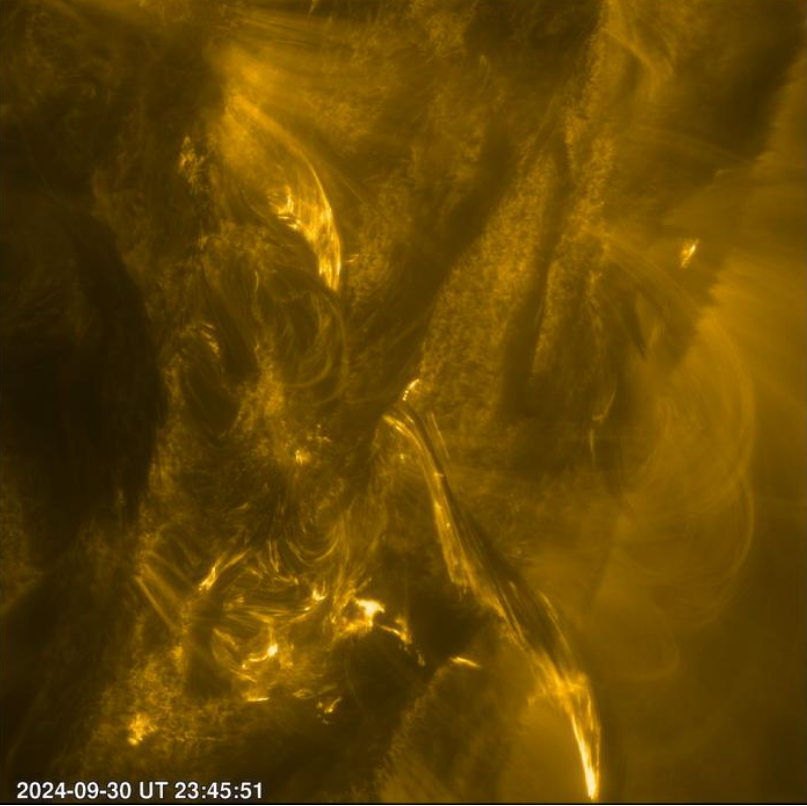

On Sept. 30, 2024, Solar Orbiter came within 27 million miles (43.3 million kilometers) of the sun, when it witnessed the eruption of a medium-class solar flare. Thanks to four of Solar Orbiter’s instruments working in unison to observe the flare, scientists have, for the first time, seen how smaller magnetic instabilities can build up into a large flare, like an avalanche on a snowy mountainside originating from a relatively small disturbance.

“We were really very lucky to witness the precursor events of this large flare in such beautiful detail,” research lead author Pradeep Chitta of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Germany, said. “We really were in the right place at the right time to catch the fine details of this flare.”

Solar flares are the product of magnetic reconnection. This is when magnetic field lines on the sun, laced with high-energy plasma, become taut and snap, releasing huge amounts of energy before the field lines reconnect. The precise origins of solar flares, however, have been secretive. Are they a single powerful eruption, or an accumulation of smaller reconnection events? For the 30 September flare at least, Solar Orbiter found the answer.

Starting with its Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), Solar Orbiter witnessed the generation of the flare over the course of 40 minutes. EUI detected changes in the magnetic environment of the sun’s corona local to the eruption point of the flare, capturing details as small as a few hundred kilometers on timescales of less than two seconds, which is the time covered in each image frame.

The spacecraft saw an arching filament made from entwined magnetic fields carrying plasma and connected to a cross-shaped region of magnetic activity laced with more magnetic field lines. It watched as the region grew increasingly unstable, field lines snapping and reconnecting, releasing bursts of energy that appeared as bright points of light.

These bursts were the beginning of the avalanche. They triggered a chain reaction of increasingly powerful reconnection events. At one point, the arching filament detached from one of its anchor points on the sun and launched out into space, blown by the ferocity of the solar wind. The cascade of smaller reconnection events quickly gathered steam before culminating as a medium-class flare.

“These minutes before the flare are extremely important, and Solar Orbiter gave us a window right into the foot of the flare where this avalanche process began,” said Chitta. “We were surprised by how the large flare is driven by a series of smaller reconnection events that spread rapidly in space and time.”

Three other instruments aboard the Solar Orbiter – SPICE (Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment), STIX (X-ray spectrometer/Telescope) and PHI (Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager) – also observed the flare, measuring events at different depths in the sun’s atmosphere, from the outer atmosphere, the corona, all the way down to the visible surface of the sun, called the photosphere. They captured waves of giant blobs of plasma, which gained their energy from magnetic fields, raining from the corona down onto the photosphere.

“We saw ribbon-like features moving extremely quickly down through the sun’s atmosphere, even before the main episode of the flare,” said Chitta. “These streams of raining plasma blobs are signatures of energy deposition, which get stronger and stronger as the flare progresses. Even after the flare subsides, the rain continues for some time.”

After the flare reached peak energy, during which X-ray levels rose dramatically, and charged particles were accelerated to between 40 and 50 percent of the speed of light, the cross-shaped magnetic region began to relax. The plasma cooled, and particle emission decreased to normal levels. Chitta described how completely unexpected it was that the avalanche process could drive such high-energy particles.

The avalanche model of weaker disturbances cascading into something more serious had previously been proposed to explain the collective behavior of hundreds of thousands of flares all across the sun, but until now, it hadn’t really been considered that it could apply to a single flare.

There are two important questions to come out of this. First, are all the flares on the sun produced as an avalanche? “What we observed challenges existing theories for flare-energy release,” said David Pontin of the University of Newcastle, Australia, who was part of the team analyzing the Solar Orbiter data.

Further observations of solar flares will be required to shed light on this.

Second, our sun is not the only star to have flares. They erupt from all stars, and some stellar bodies, such as red dwarfs, have much more powerful and more frequent flares than the sun.

“An interesting prospect is whether this mechanism happens in all flares, and on other flaring stars,” said Janvier.

The results from Solar Orbiter’s observations of the 30 September 2024 flare were published on Jan. 21 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly