Now Reading: Managing an orbital economy as space grows more congested

-

01

Managing an orbital economy as space grows more congested

Managing an orbital economy as space grows more congested

In this episode of Space Minds, SpaceNews host David Ariosto talks with Chiara Manfletti, the CEO of Neuraspace and a professor of space mobility and propulsion at the Technical University of Munich. They discuss space debris, orbital logistics and managing a new orbital economy through new initiatives in Europe and around the world.

sponsored by

Starlab Space is a US-led global joint venture and partner network that is ensuring a continued human presence in low-earth orbit. Led by Voyager Technologies, Starlab is the most advanced commercial space station under development, bringing together decades of ISS experience, Al-enabled design and global partnerships into a platform designed to scale science and industry in space. From manufacturing and life sciences to defense applications and international collaboration, Starlab is built for real work, real discovery and real continuity, providing a seamless transition from the International Space Station to the new commercial space station era.

Show notes and transcript

Click here for Notes and Transcript

Transcript

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

David Ariosto: Chiara Manfletti, you are the CEO of Neuraspace and Professor of Space Mobility and Propulsion at Technical University of Munich. It is so good to have you on the podcast.

Chiara Manfletti: It’s a pleasure to be here with you, David.

David Ariosto: Yeah. So, you began, sort of, the early part of your career in liquid rocket propulsion in Germany, then you went to ESA, the European Space Agency, and then from there you headed up the newly formed, or at least then, newly formed Portuguese National Space Agency, helping sort of build that agency from scratch, so clearly you’ve been slacking over the years, in terms of all your exploits. I always wonder how folks within the space industry, like yourself do this much, but I’m glad you’re able to carve out some time for us.

Chiara Manfletti: My pleasure.

David Ariosto: Yeah, but now you’re overseeing Neuraspace now. And I can’t think of a better time to kind of discuss this, because we were talking before the call and Neuraspace, first of all, really aims to sort of solve or address this space debris problem. But it, it’s… What your mission is, and correct me if I’m wrong, I mean, it’s happening at a moment of great transition with this orbital economy itself. We’re sort of transitioning a little bit away from the primacy of launch and focusing on more orbital logistics, and risk management, and de-orbiting, and all the sense of, like, how much stuff is actually being put up there. So, maybe we could start there. Tell me what you’re actually doing.

Chiara Manfletti: Yeah, so, Neuraspace, as you mentioned, we started off tackling the topic of debris, so the idea was to bring AI for, you know, risk assessment, collision avoidance, and optimization of all of that. Of course, things evolve over time, and as the company’s grown, as use cases have developed, of course, we’re transitioning into operationalizing space situational awareness towards automated operations, and of course, space domain awareness, which is a topic in and of itself, which has, obviously, more of a defense connotation. But, David, I think you’re absolutely right. I mean, the whole point of bringing stuff into orbit, launch, is so that we can do stuff in orbit, right? So, at some point, the launching capabilities need to enable a much wider scope of action in orbit, and I think we’re getting there.

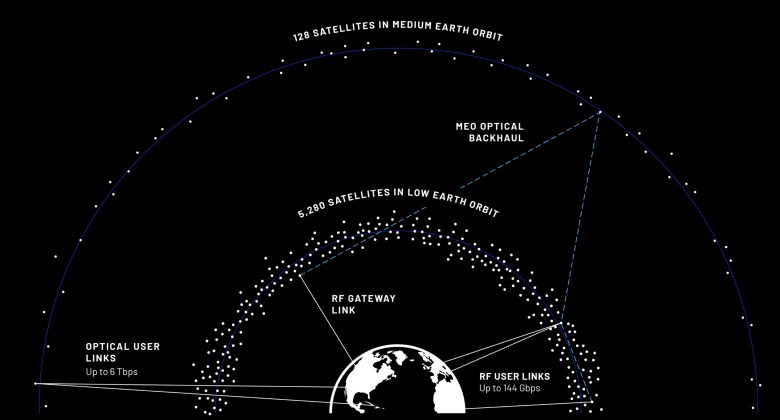

David Ariosto: I mean, it’s not to minimize the fact that, you know, you have Starship coming online, there’s all sorts of stuff that’s happening in 2026, you know, that’s going to fundamentally sort of change the landscape. So, sure, still launch-oriented, but, I mean, Starship is also a great example of this, in that the amount of payload that’s going to be put up there is going to expand just dramatically. And I’m wondering, like, what does that look like to you? When you have this much more payload, you’ve got SpaceX, that’s 42,000 satellites that they filed paperwork for, Amazon Leo, you know, not to mention the megaconstellations that China is sort of orienting towards. Yes, they’ve had some reusability issues, but broader, you have to think they’re gonna figure that out, and so this is a space that’s gonna get a lot more crowded, and I would have to think that’s gonna start playing on the books of companies in terms of what they consider in a way that they just haven’t in the past. Is that fair?

Chiara Manfletti: Yeah, absolutely. I think, so first of all, obviously, numbers going up is just, alright, exciting, right? I mean, it just means that space is becoming more and more relevant, more companies using space-based services and data, so, you know, space economy growing, and I think that that’s definitely exciting in and of itself. Then there’s, of course, challenges that come with it, as you mentioned, right? Space becoming more crowded, but, you know, if there’s a challenge, then there’s also an opportunity, both from a technology point of view, right? So you have to develop technologies to solve and tackle those challenges, and that’s what engineers love to do. And then there’s a whole economic dimension to that, as you mentioned, right? So you can’t just keep on endlessly putting assets into orbit, you have to start managing them, right? So all of a sudden, it’s not just about constellation, it’s about fleets, and fleet management, and logistics management, and it reminds us of lots of other things that we do on ground in any case, right? So you don’t just put big trucks on the street, then you also have to manage those, you have to maintain those, you have to recycle parts, so, you know, you have to make sure that they’re on the road, so…

David Ariosto: Those trucks on the street are not traveling at 17,500 miles an hour.

Chiara Manfletti: No, they’re not.

David Ariosto: So, you know, if two freights collide with each other, you don’t have this sort of knock-on effect that impacts generations to come. And I think that’s an interesting place to take the conversation, because Neuraspace really sort of sits at this intersection of data, AI, orbital operations. David Ariosto: And you would have to, by virtue of maybe the algorithms that you’re creating and the nature of how you manage these things. But you talk to people within the security industry, and there’s always this hesitation about the fact that, you know, that human judgment still matters. I don’t know how that is possible in the context of true traffic management, orbital operations, given how much is coming out there. I mean, are we looking at just sort of a post-human sort of management system, and maybe we were already at that point, but I’m curious where you see that the nature of humans in the loop, human judgment, where that sort of backstop falls, if at all.

Chiara Manfletti: Well, certainly, I mean, it’s… it’s going to be progressive, right? So we’re not going to stop having the humans in the loop from day one to the next day, for sure, but as you mentioned, the volume of what’s coming is going to be so big, and it already has become so big that just having manual processes, that doesn’t work anymore, right? So that’s, you know, why Neuraspace has grown, because we provide not just the space situational awareness information, but we provide an automated decision-making process, which allows to automate and supports, so it augments the human in the loop at this stage, right? Today, we’re about augmenting the human. At some point, the human can’t be augmented anymore from different perspectives, and then we’re… I think we’re just going to have to automate, and at some point, spacecraft are become also autonomous, right? So we’ve already seen spacecraft that, at some point, decide how to maximize their mission output by, you know, taking an image or not taking an image, by sending downlink data or not, depending on whether it’s valuable or not. And this is just going to increase, and from a point of space traffic it’s definitely going to go that way as well, right? We already see it today within own constellations. I mean, that’s what Starlink does. It’s had to introduce automated collision avoidance for its own fleet, because that was the number one source of conjunctions for them and potential collisions, their own spacecraft. And this is gonna expand to, I think, to the whole of community. There are obviously geopolitical issues.

David Ariosto: Sure, sure. That’s always infused within any of this. It’s interesting. But, I mean, you mentioned Starlink. I mean, we just recently saw the sort of plans to lower 4,000, excess of 4,000 Starlink satellites to lower orbits, principally because of near-misses with Chinese spacecraft, the growing questions of congestion. You know, it seems that we… this question of, you know, orbital traffic management being a more automated system governed by algorithms and, you know, having the humans not out of the loop, but in a sort of a tangential role, we’re fast approaching that, I would think, just by virtue of the sheer volume of content that… or it’s not content, infrastructure that we have out there. And I wonder if any of that gives you pause, and makes you, you know, think, well, where could this go off the rails here?

Chiara Manfletti: Well, I tend to be someone who’s more optimistic, so I don’t necessarily get driven by concern, but I obviously think that we do need to be cautious about how we go about it, right? So, of course, when we talk about AI and AI-based decision-making, then there’s always a topic about it being explainable, right? So, still, it has to be somebody has to be able to understand why the decision was done the way it was. So, of course, there’s a whole ethics discussion behind what we can do and what we should be doing and not doing with AI. What I find exciting about what we’re doing today, of course, is that because, you know, the population of objects is growing because satellite operators are starting to talk with one another about how they could communicate. Because there’s companies like Neuraspace that, you know, try and foster that in ways which are more automated, more machine-to-machine, then we’re testing out what makes sense from also from a technical point of view, right? So it’s not a one-shot thing, but we are iterating. What could be a good scenario is the rules of the road according to which, then AI-based decision-making, or I’d say automated decision-making could take place.

David Ariosto: You know, I remember years ago, I had a conversation with Pete Warden, who was a former director of NASA Ames, and Pete had been working a lot in tandem with Google, in terms of different quantum constructs, and how that might be applied in terms of air traffic control, and just the nature of so many different possibilities that oriented just terrestrially. And I would think that that sort of burgeoning capacity in the quantum realm would ultimately apply long-term, in terms of just the nature of the sheer multiplicity of options, or multiplicity of eventualities that could kind of be a part of orbital traffic management and risk mitigation, and how to govern constructs in terms of so many different variables, in terms of, you know, vectors and orientations and the like. And I wonder, like, what are the frontier aspects of science and technology that you’re looking at that kind of govern this forward-looking approach in terms of how you think about the future of orbital traffic management?

Chiara Manfletti: Well, as such, when we think about orbital traffic management, we don’t necessarily think of managing the traffic itself, but about vehicles being more autonomous themselves, right? And then, of course, there is a dimension to it, which is about, you know, making sure that they’re resilient, they stay safe, and they don’t collide, right? So, it’s about maximizing mission output and, you know, saving resources in orbit. And in terms of cutting-edge research that’s being done today, of course, there’s different types of AI methodologies that we’re applying, looking at what kind of patterns we can infer about how objects behave in orbit, what we could also infer about how objects will behave in future in orbit, you know, going to what you were saying about mapping the landscape around you so that you can actually decide what the actual potential configuration will be that you’ll be confronted to, what is the most likely future that you’ll be confronted with. So what are those behavior patterns? That’s on the one hand. But then also in increasing the speed at which things are being computed, right? So even, you were mentioning quantum. Quantum computing is something that is also being looked into, to enhance the speed. So quantum and AI are being looked into to enhance the speed of computations that are needed behind all of that.

David Ariosto: It’s almost like the marriage of the two of those is sort of where these things seem to be headed in some ways.

Chiara Manfletti: Yeah, absolutely. And I mean, you were mentioning Pete Warden and air traffic, and I definitely think that we’re going to be seeing something similar, not just in space, but if you think about the whole topic of UAVs, I think that’s just very much unregulated and just as much of a potential mess, where, let’s say, that there’s an increasing dimension, which is also orbital mechanics. It kind of dictates which orbit you’re in, right? There’s energy… the equation of energy conservation tells you that if you have a certain energy, you’re going to be in a certain orbit. For a UAV, that’s not quite applied. So, I think it’ll be interesting to see how the things that we learn also in space, and how things are evolving in UAVs, how these two worlds are also going to merge in the future for more autonomy and, or as you said, orbital traffic management. I mean, that makes… it’s a great point, because, you know, we always talk about the different layers within orbit, you know, LEO and GEO and, you know, geostationary and all these things, but…

David Ariosto: There is an extra layer in terms of our own, sort of, terrestrial layers, and the stratospheres when you talk about UAVs and the like, and it’s almost like we have this compiling layered cake that is both Earth and beyond it, that now has an increasing amount of assets, and there are gaps in those assets. I would imagine, not only in terms of debris. Because you can only contract something that’s so big. But I imagine there’s a decent amount of classified assets that you may or may not be privy to. So how do you take that into account and sort of recognize that your own algorithms might have notable gaps in terms of how you position and guide and advise and create structures for collision mitigation when you might not have all the information?

Chiara Manfletti: Well, yeah, I mean, that’s one of the big questions also when we discuss regulation that’s been putting forward today, right? I’m sure you’re aware of the fact that today we’re discussing something called the EU Space Act, and…

David Ariosto: I was just about to get to that.

Chiara Manfletti: …goals thought around, you know, how much sharing and what you should share between operators, and, you know, forcing people to share everything is probably not going to work. So, at some point. I think regulation also needs to be technology agnostic, and on the other hand, the platforms, be they UAVs or spacecraft. They’re gonna have different levels of sensory information coming in. Those that are gonna be, let’s say, open, unclassified, things that we’re all happy to share, and then there’s gonna be, let’s say, more short-range detect and avoid kind of technologies that are, gonna become more and more sophisticated, going from, you know, as I said, long range to very short-range technologies that will, yeah, will be required on a spacecraft to make sure that it’s safe, not just from a collision point of view, but also, you know, somebody not coming too close for comfort.

David Ariosto: Well, since you mentioned it, the EU Space Act, let’s jump right into it, because, you know, for those who are not as familiar with, from a regulatory perspective, this is, and correct me if I’m wrong, this is sort of an effort to effectively harmonize… well, there’s a lot of things that are baked into this, but at least in terms of space degree mitigations, it’s an effort to sort of harmonize rules, making operators more responsible for degree avoidance, collision avoidance. I think there’s mandatory subscription to services that’s part of this end-of-life disposal, you know, quote-unquote, deorbiting. But there’s also this question of cost, right? And how much it will affect space companies. How will those costs potentially be passed on to customers? What will that do to the market itself in terms of growth? I wonder if you have a perspective here, like, and in that same vein, is there a realistic path to enforcing a degree of space sustainability and those norms without a single regulator, or at least a clear-cut individual groupings or regional regulators that govern large swaths of the market.

Chiara Manfletti: So I think there were multiple layers to your, to your question.

David Ariosto: I threw a lot at you there.

Chiara Manfletti: Yeah, it’s all good. I mean, it is a complex piece of regulation that the EU put forward. Ultimately, of course, they try and push forward a more harmonized approach in Europe, and they try and emphasize the importance of being space… well, to be sustainable in space, both from an environmental point of view, as well as from an economic point of view. I mean, what we’re seeing today is that it’s not really regulated, right, in terms of these space sustainability issues, and we see, you know, Starlink taking measures, and others taking measures from a technology point of view to make sure that they can be sustainable, because it makes sense from an economic point of view, customers that are subscribing with us and pay for our services do so because they have a need to ensure that their assets stay safe, right? So there’s… I think there’s room for regulation to come. These are costs that companies are incurring willingly, today, right? So I don’t… of course, that if it’s enforced, then all the companies will have to assume these costs. This is clear. On the other hand, we’re also creating markets, right? So there’s companies that are providing space situational awareness services, there’s companies that are going to de-orbit, there’s companies that are going to refuel, there’s companies… we’re talking about mobility in orbit, you know, more than just launch, right? So, although we may be increasing costs locally in one aspect, because people are going to be subscribing to service. They will be reducing costs of operations, right? Again, going back to imagine having to manually go through thousands of conjunction data messages a day. You’d need an army of operators, of human operators on ground. Imagine having a software doing that, right? So, cost balances off, and at the same time, you’re creating a new market. So, it depends on how micro or macroscopic you look at it.

David Ariosto: But that seems to be the pitch, right? I mean, in order to convince operators that investing in space safety is a business enabler, and not just sort of a compliance cost, that seems to be the elevator room pitch that you’ve got to make in terms of this next paradigm that we’re all confronting.

Chiara Manfletti: Well, look, I mean, when we started off, we had Neuraspace approaching satellite operators, you know, presenting our solutions, presenting our thoughts, presenting our vision about where things are going. And today, we are approached by satellite operators who seek our services. So I think that, yes, it’s still a pitch that needs to be done, it’s still a budget line with many companies that didn’t exist before, that needs to exist. And if we look at new companies, startups, of course, and they’re, you know, they want to put satellites in orbit, and it’s not there for first priority, thinking about some collision that’s going to happen in two years, because they still… they have to deliver their spacecraft in orbit first. But after that, as I said, they come to us, right? So they clearly see a benefit and need for addressing this pain than they have all of a sudden. So I think things are going to be moving. clearly we need to have a way of addressing space sustainability, and as I said, I put the caveat on the word where I say sustainability, meaning both environmental and economic, right? Because nobody, or very few would do it just because it’s environmentally something that you need to do.

David Ariosto: For sure.

Chiara Manfletti: There needs to be also an economic driver, yeah. Governments push for something which is environmentally, important only, companies or industry push for something that’s both.

David Ariosto: But it, I mean, it… not only in terms of congestion with the existing satellite infrastructure that’s up there, but in terms of debris that we have, I mean, we haven’t talked about Kessler too much within the course of this, the Kessler effect, or, you know, the nature of sort of this exponential increase in debris over time as particles sort of interact with other particles and collide. But I’ve heard it described that if humanity never launched another rocket into space, never sent another satellite up there, that the debris field around the Earth would continue to grow by virtue of these interactions. First of all, is that fair? Is that an accurate statement before we sort of move on?

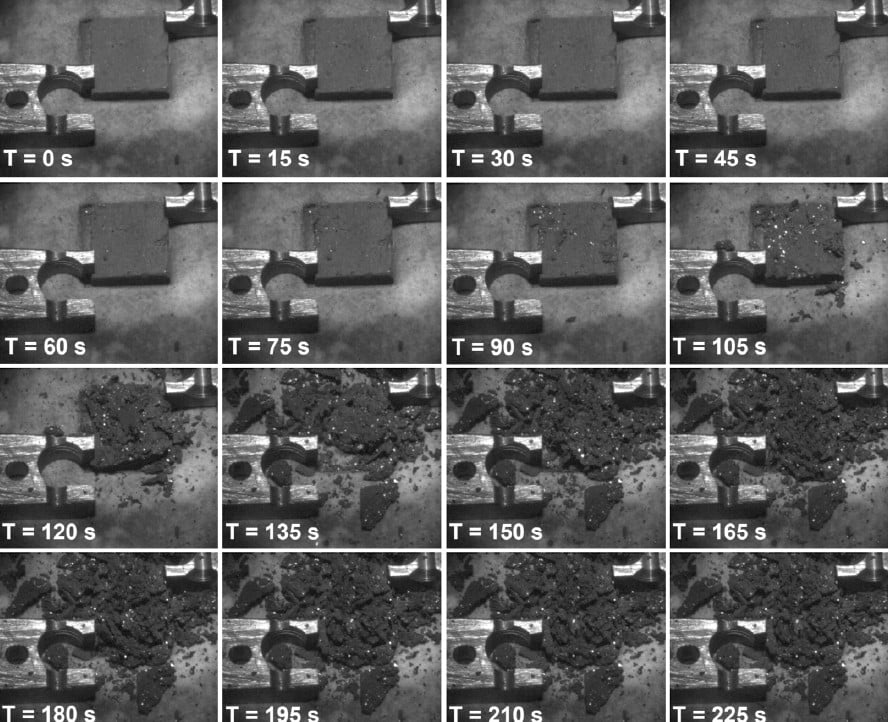

Chiara Manfletti: That is… that is the Kessler syndrome, and there’s also just to complement, if I may, David, the bigger the objects, the higher they pose as a risk, because obviously they’re bigger, there’s a higher likelihood that they’re going to get hit, and a likelihood that they’re going to fragment into many more particles, right? So there’s… there was a paper that was published a number of years ago that mentioned something like 50 most dangerous or critical objects in orbit, just because they’re very big and defunct, and they’re not being removed from orbit. So yes, that’s correct.

David Ariosto: Now, but it didn’t… I mean, and I’m gonna dig back into history, because I’m curious where you were at this moment, but I’m gonna pull us back all the way to 2009. And this is, like, I think it’s, like, about two full years after a Chinese anti-satellite test, ASAT test, that, you know, created a debris field, and there was a lot of concern about that, and you know, the nature of debris and how that affects the sort of different orbits, but, there was a, an Iridium communications satellite, and this sort of derelict Russian Strela-class orbiter that was, like, swooping over Siberia on a collision course in excess of, like, 20,000 miles an hour, and when the two of them smashed together, and there’s all kinds of controversy about who’s supposed to get out of the way. I think the old Soviet satellite, you know, couldn’t position because it had no longer propulsion on it. But it was, like, something like 2,000 shards of debris measuring at least, like, four inches in the diameter, and they were strewn around the Earth, and it was one of the worst collisions in space history. And it seemed like after that moment that we started to think about space debris and the implications, both in telecoms and national security and, you know, the growing nature of just how much stuff is up there more seriously. Is that fair, first of all? And second, like, where were you during all this?

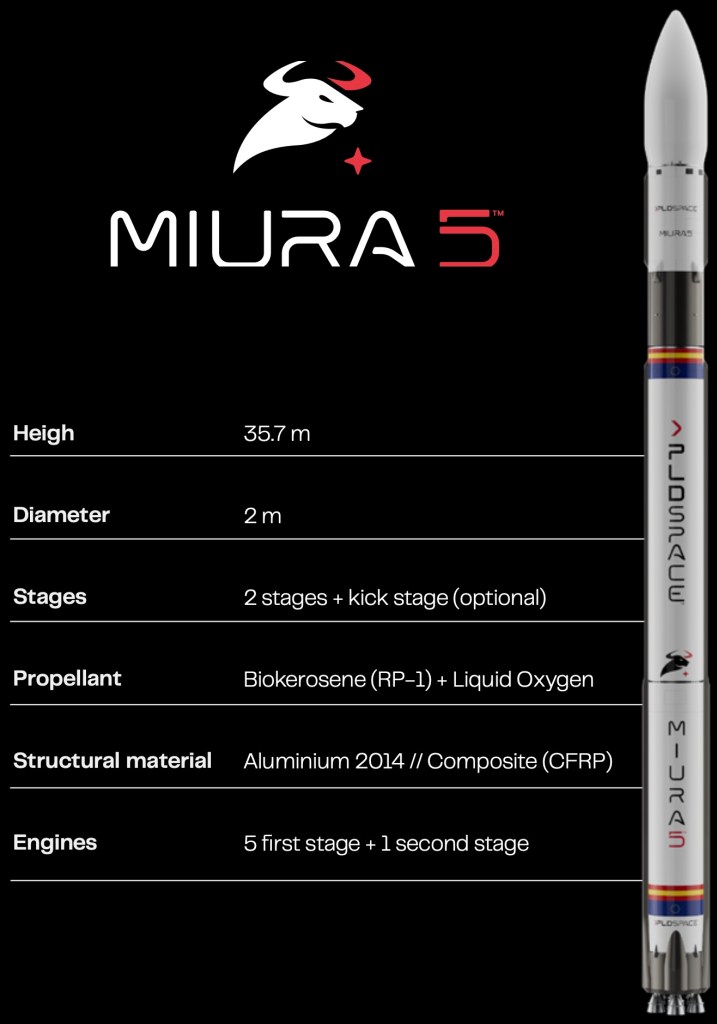

Chiara Manfletti: Well, actually, in 2009, I was still at the German Aerospace Center doing research as a propulsion research engineer, so I wasn’t into collision avoidance at all, but I was working systems, right? And one of the things, going back to regulation, is do we want to impose that spacecraft have to have propulsion system on board so that they can actually maneuver out of harm’s way, or a collision course, should land.

David Ariosto: That actually blew my mind. I didn’t know that they don’t… that not all systems up there have their own propulsion systems.

Chiara Manfletti: Oh, most of them, actually.

David Ariosto: That’s born of my own ignorance, I guess, but it’s fascinating in terms of that.

Chiara Manfletti: It is. Scary. Scary fascinating.

David Ariosto: Terribly scary.

Chiara Manfletti: Yes, it is. Terribly scary.

David Ariosto: I mean, it has, like, a little bit of a Russian roulette quality to it in terms of, you know, just the nature of, you know, collisions being degree inevitable if you have many of these things that simply can’t get out of each other’s ways.

Chiara Manfletti: I mean, space is big, right? So it used to be okay, there weren’t that many spacecraft in orbit, right? So the likelihood of something hitting you was very low. And still, it remains… I mean, we were talking about actually knowing what kind of objects are up there, and actually knowing exactly where they are. One of the biggest challenges that we still face today is a data issue, if you will, right? Knowing exactly where objects are, even spacecraft. Nowadays, spacecraft, they want to understand what their effective risk of a collision is. So I’m sure you’ve seen these images where you have the spacecraft as a dot, and then you see a big ellipsoid around it, which is the likelihood of it being in a certain region, right? So as long as these big areas of uncertainty are huge, then satellite operators may decide not to move, rightly so, because they could be leaning into it. Do a conjunction or a collision, rather than moving out of harm’s way, right? So, so it used to be okay, but I think nowadays it’s not okay anymore, and it’s getting more and more not okay. On the other hand, we’re still facing challenges of actually having commercial off-the-shelf propulsion systems, which are reliable. There’s a number of companies that have also come up, right? So, complementary to companies like Neuraspace, providing SSA information, data, intelligence, and operationalizing that data so that satellite operators can automate, and it’s actually a manageable challenge that you have. You also have to have these, incredibly good propulsion companies that can provide commercial off-the-shelf propulsion systems that can do those collision avoidance maneuvers.

David Ariosto: To your point, to the nature that space is big, I think all of us, or many of us in the space industry, have seen these animations that you often see on LinkedIn, or YouTube or something to that effect, and that talk about space debris. And it looks like the Earth is entirely surrounded in a way that’s almost impenetrable. And it’s a real misnomer in terms of the description. I mean, yes, there’s a lot of space debris out there, but it’s so voluminous in terms of the amount of area that, you know… it… it does… Kind of create this sort of question that… are we representing the nature of what space debris actually looks like in public mediums accurately? I don’t know that we are. Not to minimize the nature of space debris, but it is such a vast area here, and, you know, when we talk about Kessler and other aspects, these are concerns, but maybe more long-term. Now, that starts to change when you have 42,000 satellites from SpaceX and Amazon Leo, and mega-constellations from the Chinese going on orbit, but I wonder if you can address that, in terms of just informing the public, informing companies, investors, governments, but also, sort of. hewing to this general understanding that we have some room to work with here.

Chiara Manfletti: Yeah, so indeed, obviously it’s two different dimensions. One is the debris issue, and the other one is actually active satellites that are capable of potentially maneuvering or doing other things in orbit. When it comes to the debris, and as you were saying, these images that you see, of course, partially it’s a scale problem, right? So if you have a 1 centimeter debris, and you want to show it in orbit, then if the Earth is, like, 2 centimeters in diameter, you can’t see that little dot, right? So it’d be difficult. I don’t know if you’ve seen images of, like, solar flares and the Earth in scale. You know, also the Earth kind of disappears in comparison to those coronal mass ejections that happen. So, obviously, we do have a bit of an image difficulty in…

David Ariosto: That’s space in general, right? I mean, just the distance is so vast, and we talk about, like, Proxima Centauri and other star systems, I mean, it’s just… it’s just hard to wrap your mind around, even the closest star system.

Chiara Manfletti: But there are… yeah, but there are millions of objects that are, you know, larger than just a millimeter in orbit that could potentially, and you were mentioning some of the velocities, right? You were mentioning them in miles per hour, which is not units I work with, but, you know, very, very fast. So, you know, even very, very tiny little objects can really do a lot of harm. Maybe not to a, you know, a big 8-ton spacecraft, but if you’re a cubesat, then, you know, even a few millimeters can really hurt you. So the question is, okay, is debris an issue in terms of life terminating, or is it something that also impacts the performance, right? I think there was a very nice image that circulated around of one of the Sentinel spacecraft, where they had an impact on one of the solar arrays, and they noticed, because there was a power fluctuation, right? So, the life expectancy of spacecraft also decreases. And, you know, that, that can bring us to the whole subject of insurance, and premium pricing, and the health of spacecraft in orbits, but… and we can get to that later, right? So, for sure, let’s say that debris is something that is, is, is going to grow if we don’t tackle it. For sure, if there’s a growing number of spacecraft, if these, also these big and larger spacecraft aren’t taken down. I think one of the challenges that we’re facing today is still that there’s a lot of spacecrafts still going up that don’t have maneuvering capability, so you’re literally putting, you know, sitting ducks in orbit that are circling at very high speeds. And you don’t necessarily have these approaches to fleet management, so how am I going to take these spacecraft down, especially if they’re at higher altitudes, right? So, okay, if you can use the atmospheric density to have them de-orbit, then that’s okay. How long is it gonna take? I mean, I’m sure you’ve heard this conversation about the 5-year, the 25-year. I still feel that 5 years is a massive amount of time. Just imagine, and you’ve heard this as well, but, you know, imagine you just stopped your car for 5 years on the side of the road, and it’s like, oh yeah, it’ll sit there for 5 years, somebody’s gonna come and pick it up, and then it’ll just disappear. It just feels very old and, you know, belongs to a different millennia.

David Ariosto: Well, just the technology. The technology is so vastly different from now to 25 years ago, or 25 years in the future. You can kind of see the nature of these things, but it’s fascinating, and you know, you’ve mentioned in past interviews that I’ve seen, when you talk about innovation, and the nature of that being ascribed usually to technology. But the need for innovation being structured, both in terms of how companies orient themselves, in terms of regulatory structures, legal codes, just the nature of all of our… all of our, kind of the iterations that kind of stitch together society kind of being reinvented, or at least reconsidered in this brand new paradigm that… and I say brand new, because it is… You know, we’ve been operating in space for quite some time, for the better part of the last century, and yet this explosion of commercial technologies, and the way that LEO seems to be almost akin to this new factory floor, so to speak, and the influence of AI in governing these systems. I mean, just, it’s sort of this brave new era that we’re all kind of coming upon, and yet, the structures that we have, especially from a regulatory perspective, I mean, you know, the biggest most overarching treaty was written two years before the first moon landing. So, I mean, these are old kind of regulatory structures that maybe are not as up-to-date as they need to be.

Chiara Manfletti: Without even binding, right?

David Ariosto: Not even binding, can’t. And I wonder how you bridge that. Now, on the other side, you know, you have aircraft control, so you have very different systems in the US and Europe and China, and yet planes interact all the time between the various regions, and yet, it seems like we have this emergence of different structures as pursued by different kind of regional hubs, being Europe, China, US, and not a real clear sense of how they’re going to interact. That seems a problem.

Chiara Manfletti: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, part of it is obviously due to the geopolitical situation that we’re experiencing. Part of it is due to, obviously, economic sovereignty that countries want to put forward. They don’t want to have rules being imposed by somebody else. Clearly, but, you know, I think that, you know, we’ve come to certain agreements in the past, maritime traffic being, for example, one of them, the AIS system, where you have ships that automatically have to have this automatic identification system, and if they turn it off, then you know that they’re up to no good, because they’re doing some piracy. This is something that is being… that is adopted worldwide in the meantime, right? So that… I think that’s pretty neat, and I think we can potentially come to a sort of framework that is similar. In the meantime, you’re absolutely right, everybody’s sort of cooking in their own kitchen, but what I think is the positive side of this is that as long as there is some cooking that’s being done, we’re also pushing for new technological solutions, right? So, hopefully, as I was saying before, regulations should be technology agnostic, but should also be technology-informed. So, you know, as the U.S. imposes certain requirements… I mean, we still have countries that have no rules in terms of upper stages, and, you know, leaving upper stages in orbit, I think, again, this is for me, like, the dark ages, the Middle Ages. It’s hard to understand, right? So, if nations push these things forward, I think globally will benefit us whole, as a whole. And then, of course, we need to continue having conversation as to what is the minimum level, of data sharing, that we can, accept internationally that can work, right? So, system of systems, having, you know, potentially regional hubs that, work on a trust-based system, is something that can work. I’ve used the word federated systems before, but I understand that the word federated is politically difficult. So system of systems, right, where, you know, each hub is a trust center. You can share that data, and what actually only comes out is information, right? So, one of the arguments that I bring is, you know, do you really want to force operators to share full transparency on their full data set, or do you actually really need to know what the intelligence is that you can extract from that data? Okay, there’s something coming, you have to move, right? You don’t actually have to know everything, you just need to know there’s something coming, you have to move. So, trust centers can have that whole data sharing, and then there’s a certain other level of information or intelligence can be passed on. That could be a system that could work in difficult geopolitical situations, and in the meantime, we can also discuss, you know, what kind of automatic identification system of sorts we can put forward in orbit, for, you know, more international collaboration.

David Ariosto: That seems like a good place to leave it. Something’s coming, you have to move. AI, orbital traffic, space piracy, you know, we covered a lot in the course of this conversation, but it was a real pleasure having you on the program. Chiara Manfletti, CEO of Neuraspace and professor of space mobility and propulsion at the Technical University of Munich. Thanks so much for joining us.

Chiara Manfletti: Thanks for having me, David.

David Ariosto: Alright, great. That was great.

About Space Minds

Space Minds is a new audio and video podcast from SpaceNews that focuses on the inspiring leaders, technologies and exciting opportunities in space.

The weekly podcast features compelling interviews with scientists, founders and experts who love to talk about space, covers the news that has enthusiasts daydreaming, and engages with listeners. Join David Ariosto, Mike Gruss and journalists from the SpaceNews team for new episodes every Thursday.

Watch a new episode every Thursday on SpaceNews.com and on our YouTube, Spotify and Apple channels.

Be the first to know when new episodes drop! Enter your email, and we’ll make sure you get exclusive access to each episode as soon as it goes live!

Space Minds Podcast

“*” indicates required fields

Note: By registering, you consent to receive communications from SpaceNews and our partners.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly