Now Reading: Massive grazing collision created Mercury, new theory says

-

01

Massive grazing collision created Mercury, new theory says

Massive grazing collision created Mercury, new theory says

- How did planet Mercury form? Scientists have been pondering this question for a long time.

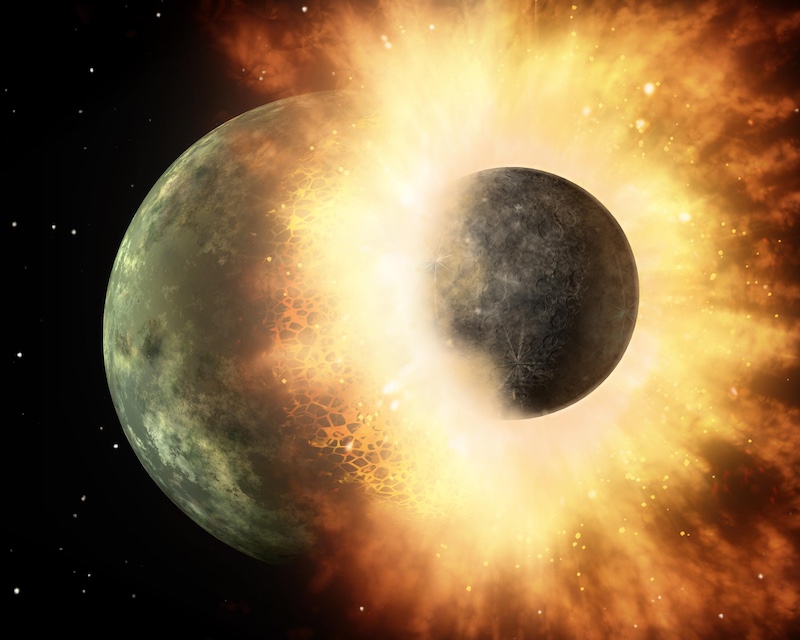

- According to new research, Mercury originated from the massive grazing collision of two bodies of similar mass.

- Collisions like this one were common in the early solar system billions of years ago. In fact, they likely accounted for about 1/3 of all impacts.

Massive grazing collision created Mercury, new theory says

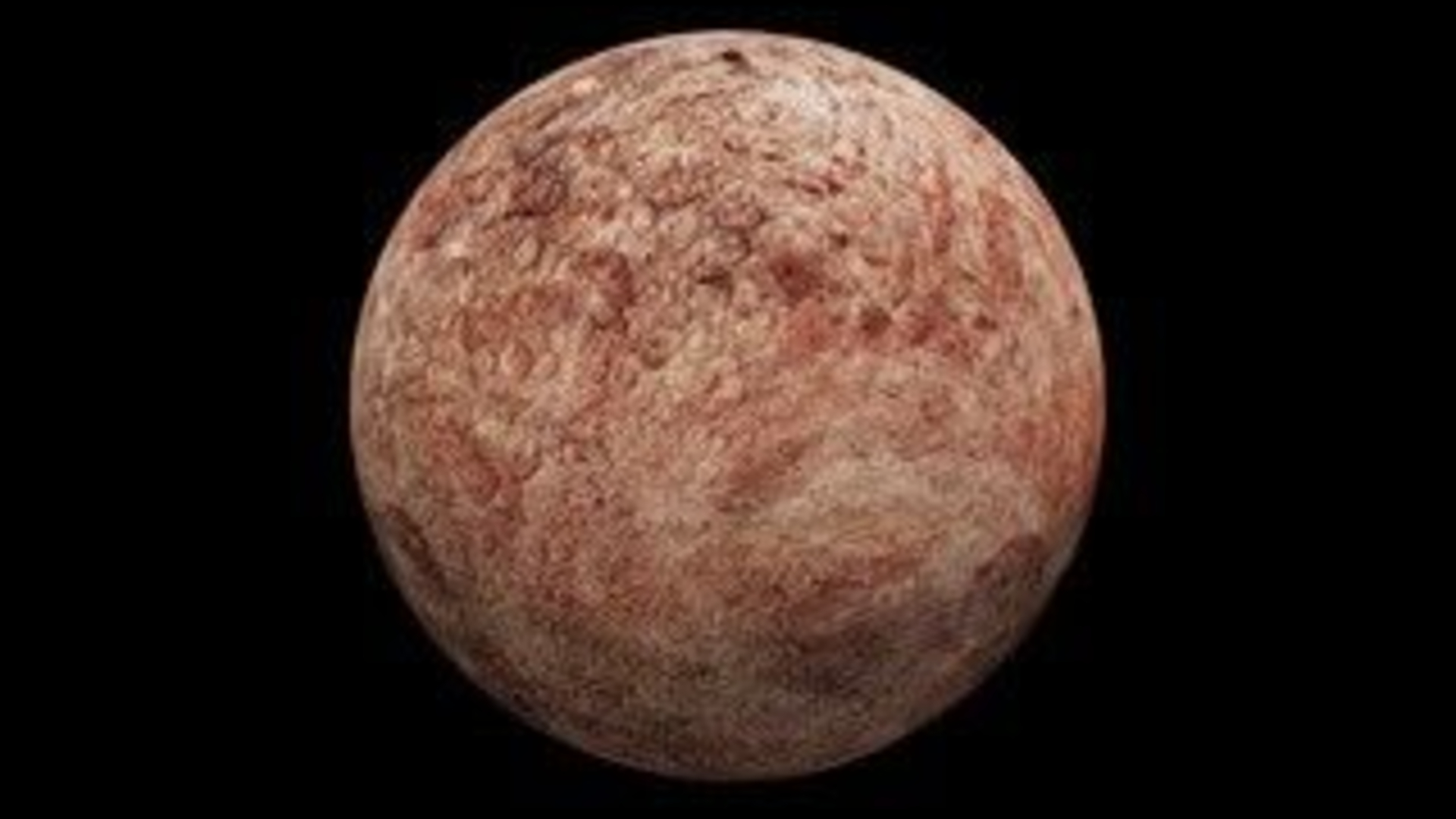

Mercury is the smallest and innermost planet in our solar system. It looks a lot like our moon at first glance, but Mercury’s its own world, with unique geology and history. Scientists have been trying to figure out how it formed for a long time. On September 22, 2025, a new study from researchers in Brazil, Germany and France shed some new light on the question. The researchers said Mercury might have formed when two bodies of similar mass collided in a grazing impact. The collision would have stripped away about 60% of Mercury’s original mantle.

Previously, scientists thought Mercury formed into the world we see today when it collided with a larger body, or protoplanet. But those kinds of impacts are rare. A grazing collision between two bodies of similar mass, however, would more easily explain oddities such as Mercury’s disproportionately large metallic core.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed findings in Nature Astronomy on June 27, 2025.

How did Mercury form?

Despite its superficial resemblance to our moon, Mercury is a unique and strange world. For example, researchers have found evidence for a possible 10-mile-thick (16 km) layer of diamonds between the core and mantle of this planet, along with salty glaciers that could even be habitable.

And until now, scientists haven’t fully understood how Mercury formed. Surrounding its iron core is a relatively thin silicate mantle. In fact, the solid inner core and the molten outer core together take up nearly 85% of the planet’s radius. That’s much more than any of the other rocky planets. This posed a mystery. As the paper states:

The origin of Mercury still remains poorly understood compared to the other rocky planets of the solar system. One of the most relevant constraints that any formation model has to fulfill refers to its internal structure, with a predominant iron core covered by a thin silicate layer.

Massive collision created Mercury

Patrick Franco at the National Observatory in Brazil led the new study into whether two similar-sized rocky bodies could form a planet similar to Mercury.

Their study used a main body – a proto-Mercury – with a mass just over 10% of Earth’s, and a 30% iron makeup. In the simulations, the researchers experimented with variously sized secondary bodies, with varying amounts of iron.

They also varied the impact velocities between the two bodies, from 2.8 to 3.8 times the mutual escape velocity. The escape velocity is the minimum speed needed for an object to escape the orbit of or contact with a primary body.

Within these parameters, the researchers experimented with collision scenarios that could have occurred billions of years ago in the early solar system.

A grazing impact

And they eventually found a setup in which Mercury grazed a similarly sized rocky object in a hit-and-run collision, leading it to lose much of its outer material. This scenario produced a planet that matched Mercury’s mass with a 5% margin, and left a core of 65-75% iron, matching Mercury’s current value of 70%. It’s strong evidence, they said, that a collision like this produced the planet we know today. Franco said:

Through simulation, we show that the formation of Mercury doesn’t require exceptional collisions. A grazing impact between two protoplanets of similar masses can explain its composition. This is a much more plausible scenario from a statistical and dynamic point of view. Our work is based on the finding, made in previous simulations, that collisions between very unequal bodies are extremely rare events. Collisions between objects of similar masses are more common, and the objective of the study was precisely to verify whether these collisions would be capable of producing a planet with the characteristics observed in Mercury.

Solving Mercury’s mysteries

The findings help solve some of Mercury’s perplexing mysteries, such as its unusual metal-to-silicate ratio and its huge core and thin mantle. As Franco noted:

Through detailed simulations in smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH), we found that it’s possible to reproduce both Mercury’s total mass and its unusual metal-to-silicate ratio with high precision. The model’s margin of error was less than 5%.

SPH can simulate gases, liquids and solid materials in motion, especially in contexts involving large deformations, collisions or fragmentations.

Where did all the debris go?

In some previous simulations, the debris from the collision simply became part of the new planet. But that doesn’t quite fit the observations. In the new model, much of the debris might simply have been ejected into space. As Franco explained:

In these scenarios, the material torn away during the collision is reincorporated by the planet itself. If this were the case, Mercury wouldn’t exhibit its current disproportion between core and mantle. But in the model we’re proposing, depending on the initial conditions, part of the material torn away may be ejected and never return, which preserves the disproportion between core and mantle.

Collisions in the early solar system

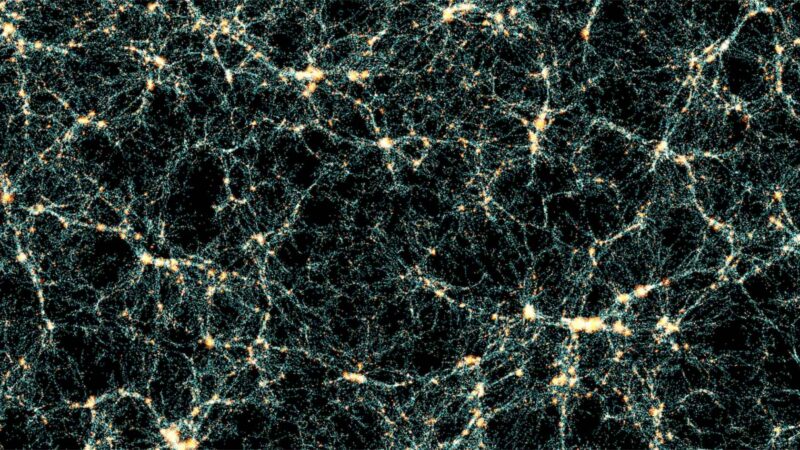

The early solar system was a chaotic place, with frequent collisions between rocky bodies. And Mercury’s strangely large core has led scientists to hypothesize that a giant collision with a much larger body might have stripped away its outer layers.

But simulations of the early solar system have found colossal impacts between very differently sized objects to be relatively rare. On the other hand, recent simulations suggest that grazing “hit-and-run” collisions between similarly-sized bodies are much more common. In fact, they likely accounted for about 1/3 of all impacts in the early solar system. And this, the new study says, is how Mercury likely formed.

As of now, Mercury is still the least explored planet in the solar system. But as Franco notes, that is changing, with much more to learn about this enigmatic little world:

There’s a new generation of research and missions underway, and many interesting things are yet to come.

Bottom line: A new study says Mercury was formed from a huge collision between two rocky bodies of similar mass.

Source: Forming Mercury by a grazing giant collision involving similar mass bodies

Source (preprint): Formation of Mercury by a grazing giant collision involving similar-mass bodies

Read more: Mercury may have a 10-mile-thick layer of diamonds

Read more: Mercury images from final flyby of BepiColombo!

The post Massive grazing collision created Mercury, new theory says first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors