Now Reading: Meteorites from Mercury: Have we finally found some?

-

01

Meteorites from Mercury: Have we finally found some?

Meteorites from Mercury: Have we finally found some?

- We’ve collected meteorites from the moon and Mars, but never Mercury. Why? It’s a mystery.

- A new study has found 2 meteorites that show strong signs of having come from Mercury.

- Mercury meteorites could provide invaluable information about the planet closest to the sun, but confirming their origin is tricky.

By Ben Rider-Stokes, The Open University. Edits by EarthSky.

Where are the meteorites from Mercury?

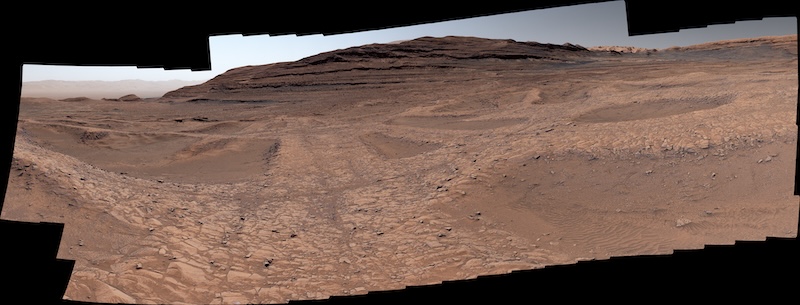

Most meteorites that have reached Earth came from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. But we have collected 1,000 or so meteorites that came from the moon and Mars. This is probably a result of asteroids hitting their surfaces and ejecting material toward our planet.

It should also be physically possible for such debris to reach the Earth from Mercury, another nearby rocky body. But so far, none have been confirmed to come from there. Why? It’s a longstanding mystery.

Now, in a new study, my colleagues and I have discovered two meteorites that could have a Mercurian origin. If confirmed, they would offer a rare window into Mercury’s formation and evolution, potentially reshaping our understanding of the planet nearest the sun.

Possible Mercury fragments

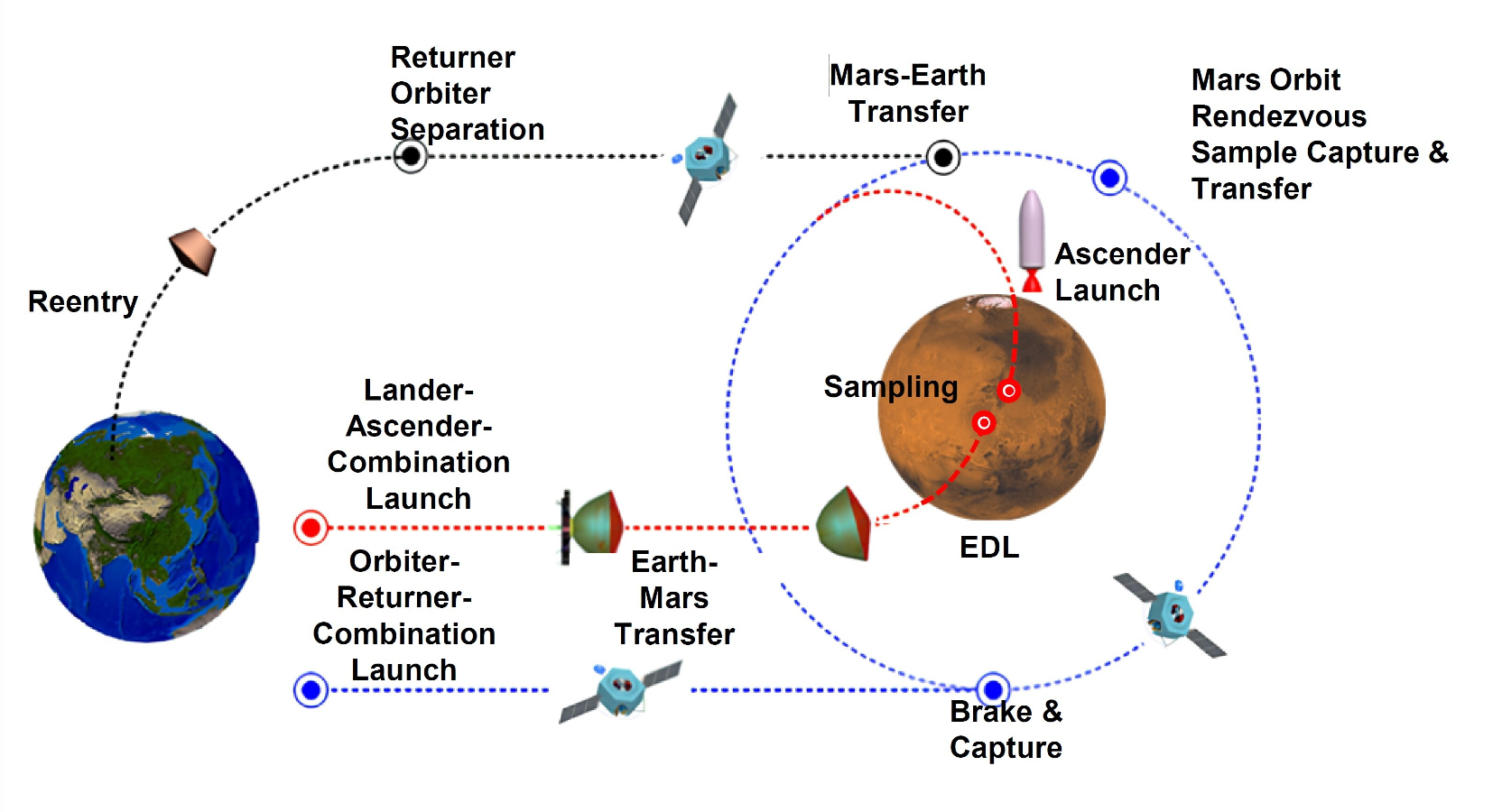

Because Mercury is so close to the sun, any space mission to retrieve a sample from there would be complex and costly. A naturally delivered fragment, therefore, may be the only practical way to study its surface directly. Such a discovery would be scientifically invaluable.

Observations from NASA’s Messenger mission have inferred the surface composition of Mercury. This suggests the presence of minerals including sodium-rich plagioclase (such as albite), iron-poor pyroxene (for example enstatite), iron-poor olivine (such as forsterite) and sulfide minerals such as oldhamite.

The meteorite Northwest Africa (NWA) 7325, found in Morocco in 2012, was initially proposed as a possible fragment of Mercury. However, its mineralogy includes chromium-rich pyroxene containing approximately 1% iron. This poorly matches Mercury’s estimated surface composition. As a result of this, and other factors, this link has been challenged.

Aubrite meteorites have also been proposed as potential Mercurian fragments. Recent modeling of their formation suggests an origin from a large planetary body approximately 5,000 km (3,100 miles) in diameter (similar to Mercury), potentially supporting this hypothesis.

Although aubrites do not exhibit chemical or spectral (the study of how light is broken up by wavelength) similarities with Mercury’s surface, it has been hypothesized that they may derive from the planet’s shallow mantle (the layer beneath the surface). But despite ongoing research, the existence of a definitive meteorite from Mercury remains unproven.

The new study

Our latest study investigated the properties of two unusual meteorites, Ksar Ghilane 022, found in Tunisia in 2023, and Northwest Africa 15915, found in Algeria in the same year. We found that the two samples appear to be related, probably originating from the same parent body. Their mineralogy and surface composition also exhibit intriguing similarities to Mercury’s crust. This has prompted us to speculate about a possible Mercurian origin.

Both meteorites contain olivine and pyroxene, minor albitic plagioclase and oldhamite. Such features are consistent with predictions for Mercury’s surface composition. Additionally, their oxygen compositions match those of aubrites. These shared characteristics make the samples compelling candidates for being Mercurian material.

However, notable differences exist. Both meteorites contain only trace amounts of plagioclase, in contrast to Mercury’s surface, which is estimated to contain over 37%. Furthermore, our study suggests that the age of the samples is about 4,528 million years old. This is significantly older than Mercury’s oldest recognized surface units, which are predicted (based on crater counting) to be approximately 4,000 million years.

If these meteorites do originate from Mercury, they may represent early material that is no longer preserved in the planet’s current surface geology.

Will we ever know?

To link any meteorite to a specific moon, planet or asteroid type is extremely challenging, but it is possible. Laboratory analysis of Apollo samples allowed meteorites found in desert collection expeditions to be matched with the lunar materials. And Martian meteorites have been identified through similarities between the composition of gases trapped in the meteorites with measurements of the Martian atmosphere by spacecraft.

Until we visit Mercury and bring back material, it will be extremely difficult to assess a meteorite-planet link.

The BepiColombo space mission, by the European and Japanese space agencies, is now in orbit around Mercury and is about to send back high-resolution data. This may help us determine the ultimate origin body for Ksar Ghilane 022 and Northwest Africa 15915.

If meteorites from Mercury were discovered, they could help resolve a variety of long-standing scientific questions. For example, they could reveal the age and evolution of Mercury’s crust, its mineralogical and geochemical composition and the nature of its gases.

The origin of these samples is likely to remain a subject of continuing debate within the scientific community. Several presentations have already been scheduled for the upcoming Meteoritical Society Meeting 2025 in Australia. We look forward to future discussions that will further explore and refine our understanding of their potential origin.

For now, all we can do is make educated guesses. What do you think?

Ben Rider-Stokes, Post Doctoral Researcher in Achondrite Meteorites, The Open University.

Bottom line: Mysteriously, scientists have never confirmed any meteorites that have reached Earth from Mercury. But a new study has found two strong candidates.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read more:

Massive collision created Mercury, new theory suggests

Mercury images from final flyby of BepiColombo!

The post Meteorites from Mercury: Have we finally found some? first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly