Now Reading: Mobile networks want to use the satellite airwaves we need to track climate change

-

01

Mobile networks want to use the satellite airwaves we need to track climate change

Mobile networks want to use the satellite airwaves we need to track climate change

At next year’s World Radiocommunications Conference (WRC-25), governments will face a choice that goes to the heart of how we monitor our warming planet. Some regulators are wondering whether to open part of the X-band — the 8.025–8.4 GHz range used by Earth observation satellites — to 5G and 6G mobile networks. Several major telecom operators have been pushing for this move, arguing that they could use this spectrum more efficiently and pay countries handsomely for the right to do so.

At first blush, this sounds like the prudent husbandry of a finite resource. But look a little closer, and what you discover is that this risks diminishing our ability to see what’s happening on the ground and at sea — just as climate risks are rising and governments need greater clarity about the forces reshaping their territory.

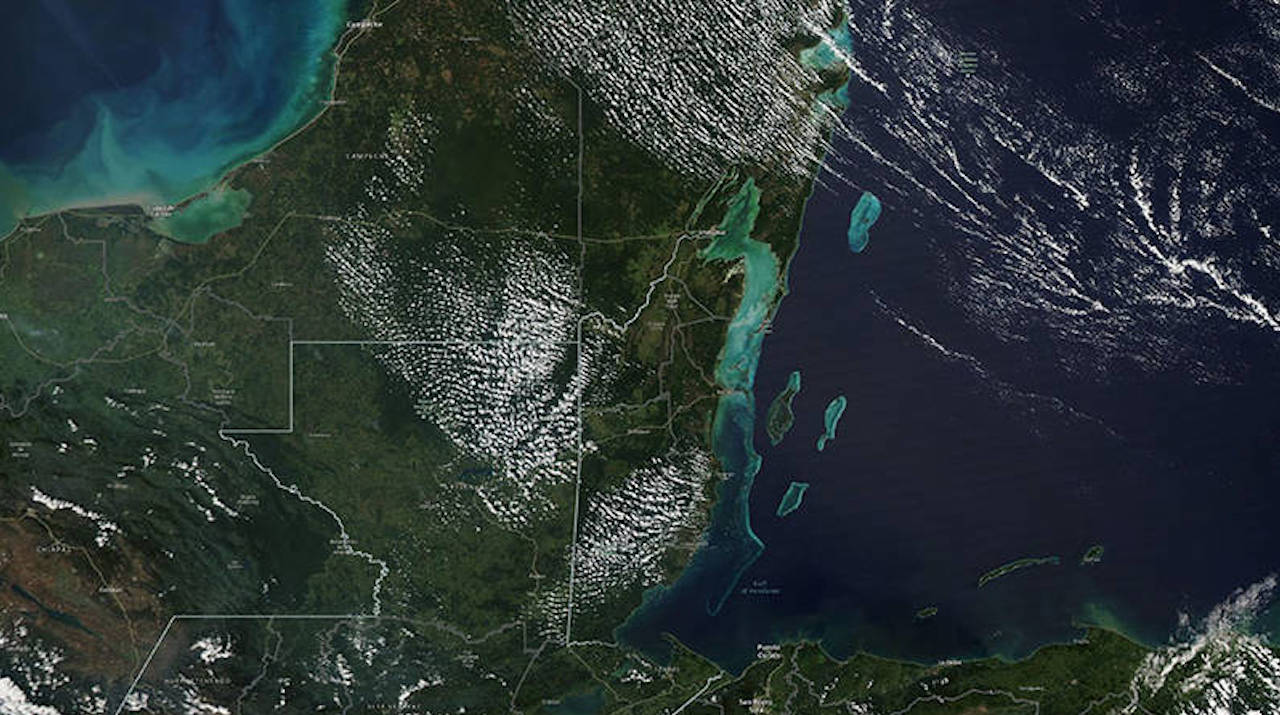

With this in mind, 11 satellite-focused companies have formed the Remote Sensing Collective to resist the change. They’ve done this because the satellites we depend on to understand the environment depend in turn on the X-band. This is the workhorse band used for downloading high-resolution imagery, which means in this context natural-disaster assessments, terrain mapping, crop surveillance, deforestation tracking and ice-sheet monitoring, as well as critical jobs unrelated to the climate, such as the observation of troop movements. The situation in which we find ourselves is relatively simple to understand, but no less serious because of it: Without a clean X-band, Earth observation satellites won’t be able to deliver the data that governments, insurers, scientists and security agencies count on every day.

The stakes, therefore, are high. Indeed, they are high across the whole spectrum, such that even Elon Musk has entered the market, agreeing to pay $19 billion for wireless communications frequencies — not the X-band — that were previously held by EchoStar. When spectrum becomes a battleground between big, wealthy players, there’s a real danger that smaller companies, including Earth observation satellite companies, lose out almost by default. They lack anything like the same amount of money or influence as their larger counterparts.

Why do telecom operators want the X-band? In short, because demand for wireless connectivity is rising, and they can see that. Their argument is that their systems can coexist perfectly well with Earth observation systems and that, in any case, they will pay governments far more for access than the Earth observation satellite operators ever could. But the studies on coexistence don’t quite paint this picture. Indeed, they show that 5G towers operating in or near the X-band would interfere with ground stations to such an extent that operators would need vast exclusion zones around every Earth observation downlink site. Protecting existing stations might just be possible; building new ones would be very difficult indeed. In practice, this would freeze the present ground segment in place and choke off the expansion needed to serve a rapidly growing satellite fleet.

And make no mistake: Governments need that expansion. However attractive telecom cash might look, states are accountable to their citizens for dealing with climate change, geopolitical tensions and extreme weather events, all of which are increasing the demand for fast, reliable imagery. When floods and fires strike, every moment counts. The armed forces need rapid, reliable intelligence. The world can’t afford to hobble the systems that underwrite societal resilience.

The international politics of spectrum allocation are now taking shape. Europe and the United States appear set to oppose opening up the X-band. Brazil and Mexico, by contrast, have signalled support for allowing the mobile networks in. Africa, the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific region have yet to nail their colours to any mast. That bloc of “undecideds” will likely determine the final outcome at WRC-27, when the binding decision will be made. Satellite operators are cautiously optimistic now; but when the financial might of the telecom sector is brought to bear on the situation, they might feel less so.

Whatever happens, the dispute itself represents a hinge moment. Spectrum has become a commodity: something industries are willing to fight over, something governments are tempted to monetize, something investors are prepared to spend eye-watering sums to secure. As competition heats up, the public-interest functions of spectrum risk being crowded out by private concerns. Earth monitoring is a vital public good that risks being set aside so that — to be vulgar — a handful of massive companies can make more money. No doubt in doing so they will be benefitting their customers. But in the long list of human wants and needs, wireless connectivity surely doesn’t come above disaster prediction and prevention, for example, or an effective defence from hostile countries.

There may not be a perfect middle ground between the two poles I’ve described, but there is a way to relieve some of the pressure: moving more data off radio frequencies altogether. Laser communications — lasercom — does not use RF spectrum. It transmits data via light, offering fibre optic-grade throughput between satellites and Earth without touching the congested radio bands. The technology has evolved rapidly in the last decade, reaching commercial maturity. The best optical ground stations available can preserve the resilience of laser signals despite atmospheric turbulence.

Lasercom will not replace RF; nor should it. Radio is indispensable for many reasons. But if governments want to avoid paying billions to defend the spectrum necessary for environmental security, they should start looking to alternative forms of technology now. There’s plenty of wisdom in the saying, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.” Diversification is smart: it reduces risk. And in this instance, it would allow us to protect the X-band.

For all the bad press they receive, smartphones are incredible pieces of technology that connect us and empower us. But in a warming, volatile century, satellites matter more than ever-greater levels of connectivity. We can’t replay a missed image of a cyclone about to reach the coast, or a drought creeping across farmland, or a glacier collapsing into the sea. Here, a spectrum choice is a climate choice, and with that in mind, regulators must see: Some bands are just too vital to compromise.

Jean-Francois Morizur is co-founder and CEO at Cailabs, a French startup developing optical communications systems for spacecraft and other industries.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly