Now Reading: NASA Researchers Probe Tangled Magnetospheres of Merging Neutron Stars

-

01

NASA Researchers Probe Tangled Magnetospheres of Merging Neutron Stars

NASA Researchers Probe Tangled Magnetospheres of Merging Neutron Stars

7 min read

NASA Researchers Probe Tangled Magnetospheres of Merging Neutron Stars

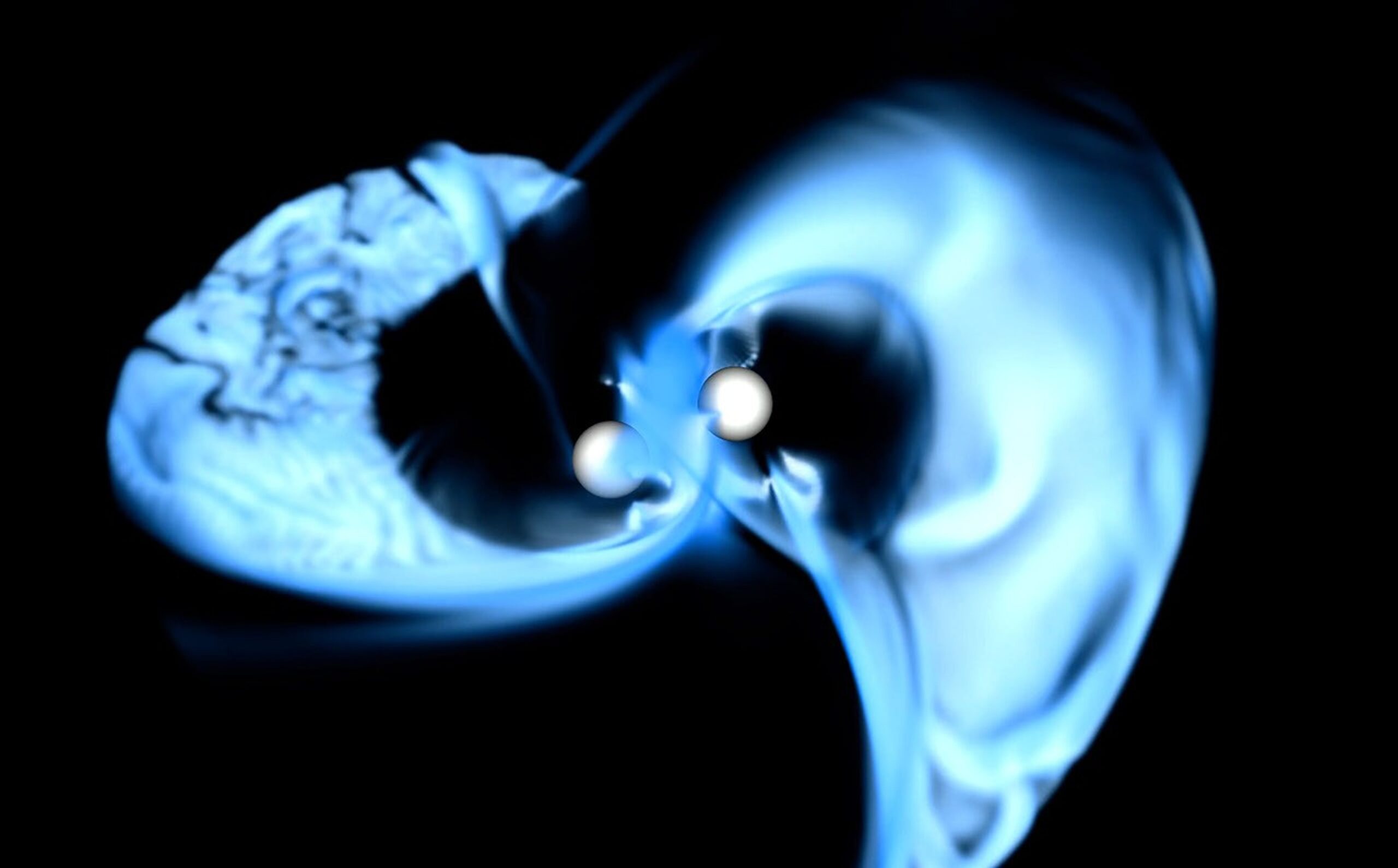

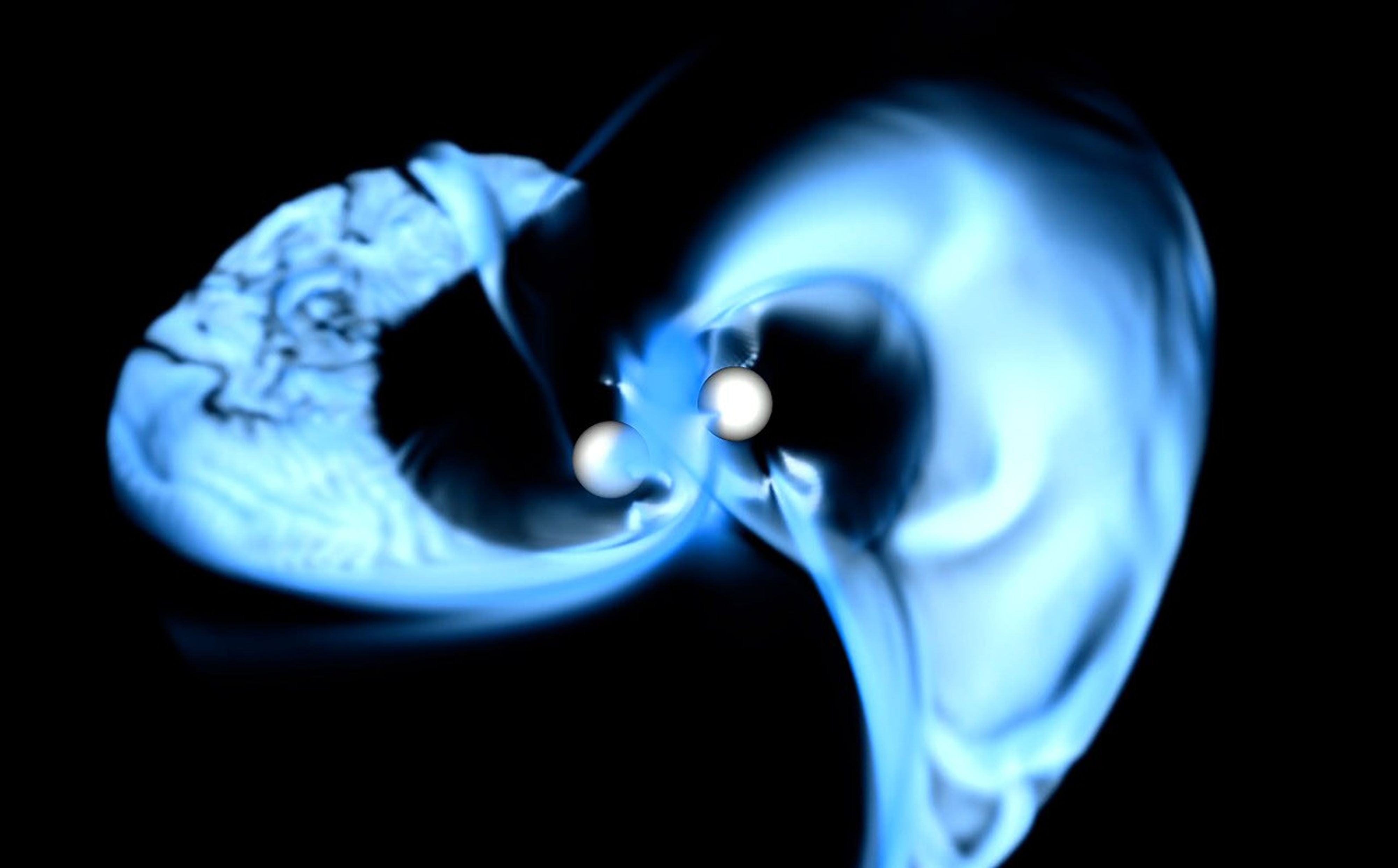

New simulations performed on a NASA supercomputer are providing scientists with the most comprehensive look yet into the maelstrom of interacting magnetic structures around city-sized neutron stars in the moments before they crash. The team identified potential signals emitted during the stars’ final moments that may be detectable by future observatories.

“Just before neutron stars crash, the highly magnetized, plasma-filled regions around them, called magnetospheres, start to interact strongly. We studied the last several orbits before the merger, when the entwined magnetic fields undergo rapid and dramatic changes, and modeled potentially observable high-energy signals,” said lead scientist Dimitrios Skiathas, a graduate student at the University of Patras, Greece, who is conducting research for the Southeastern Universities Research Association in Washington at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

A paper describing the findings published Nov. 20, 2025, in the The Astrophysical Journal.

Neutron star mergers produce a particular type of GRB (gamma-ray burst), the most powerful class of explosions in the cosmos.

Most investigations have naturally concentrated on the spectacular mergers and their aftermaths, which produce near-light-speed jets that emit gamma rays, ripples in space-time called gravitational waves, and a so-called kilonova explosion that forges heavy elements like gold and platinum. A merger observed in 2017 dramatically confirmed the long-predicted connections between these phenomena — and remains the only event seen so far to exhibit all three.

Neutron stars pack more mass than our Sun into a ball about 15 miles (24 kilometers) across, roughly the length of Manhattan Island in New York City. They form when the core of a massive star runs out of fuel and collapses, crushing the core and triggering a supernova explosion that blasts away the rest of the star. The collapse also revs up the core’s rotation and amplifies its magnetic field.

In our simulations, the magnetosphere behaves like a magnetic circuit that continually rewires itself as the stars orbit.

Constantinos Kalapotharakos

Newborn neutron stars can spin dozens of times a second and wield some of the strongest magnetic fields known, up to 10 trillion times stronger than a refrigerator magnet. That’s strong enough to directly transform gamma-rays into electrons and positrons and rapidly accelerate them to energies far beyond anything achievable in particle accelerators on Earth.

“In our simulations, the magnetosphere behaves like a magnetic circuit that continually rewires itself as the stars orbit. Field lines connect, break, and reconnect while currents surge through plasma moving at nearly the speed of light, and the rapidly varying fields can accelerate particles,” said co-author Constantinos Kalapotharakos at NASA Goddard. “Following that nonlinear evolution at high resolution is exactly why we need a supercomputer!”

Using the Pleiades supercomputer at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley, the team ran more than 100 simulations of a system of two orbiting neutron stars, each with 1.4 solar masses. The goal was to explore how different magnetic field configurations affected the way electromagnetic energy — light in all of its forms — left the binary system. Most of the simulations describe the last 7.7 milliseconds before the merger, enabling a detailed study of the final orbits.

“Our work shows that the light emitted by these systems varies greatly in brightness and is not distributed evenly, so a far-away observer’s perspective on the merger matters a great deal,” said co-author Zorawar Wadiasingh at the University of Maryland, College Park and NASA Goddard. “The signals also get much stronger as the stars get closer and closer in a way that depends on the relative magnetic orientations of the neutron stars.”

Magnetic field lines anchored to the surfaces of each star sweep behind them as the stars orbit. Field lines may directly connect one star to the other as the orbits shrink, while lines already linking the stars may break and reconfigure.

One value of studies like this is to help us figure out what future observatories might be able to see and should be looking for in both gravitational waves and light.

Demosthenes Kazanas

Using the simulations, the team also computed electromagnetic forces acting on the stars’ surfaces. While the effects of gravity dominate, these magnetic stresses could accumulate in strongly magnetized systems. Future models may help reveal how magnetic interactions influence the last moments of the merger.

“Such behavior could be imprinted on gravitational wave signals that would be detectable in next-generation facilities. One value of studies like this is to help us figure out what future observatories might be able to see and should be looking for in both gravitational waves and light,” said Goddard’s Demosthenes Kazanas.

The team, which includes Alice Harding at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and Paul Kolbeck at the University of Washington in Seattle, then used the simulated fields to identify where the highest-energy emission would be produced and how it would propagate.

In the chaotic plasma surrounding the neutron stars, particles transform into radiation and vice versa. Speedy electrons emit gamma rays, the highest-energy form of light, through a process called curvature radiation. A gamma-ray photon can interact with a strong magnetic field in a way that transforms it into a pair of particles, an electron and a positron.

The study found regions producing gamma rays with energies trillions of times greater than that of visible light, but likely none of it could escape. The highest-energy gamma rays quickly converted to particles in the presence of powerful magnetic fields. However, gamma rays at lower energies, with millions of times the energy of visible light, can exit the merging system, and the resulting particles may also radiate at still lower energies, including X-rays.

The finding suggests that future medium-energy gamma-ray space telescopes, especially those with wide fields of view, may detect signals originating in the runup to the merger if gravitational-wave observatories can provide timely alerts and sky localization. Today, ground-based gravitational-wave observatories, such as LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) in Louisiana and Washington, and Virgo in Italy, detect neutron star mergers with frequencies between 10 and 1,000 hertz and can enable rapid electromagnetic follow-up.

ESA (European Space Agency) and NASA are collaborating on a space-based gravitational-wave observatory named LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna), planned for launch in the 2030s. LISA will observe neutron-star binaries much earlier in their evolution at far lower gravitational-wave frequencies than ground-based observatories, typically long before they merge.

Future gravitational-wave observatories will be able to alert astronomers to systems on the verge of merging. Once such systems are found, wide-field gamma-ray and X-ray observatories could begin searching for the pre-merger emission highlighted by these simulations.

Routine observation of events like these using two different “messengers” — light and gravitational waves — will provide a major leap forward in understanding this class of GRBs, and NASA researchers are helping to lead the way.

By Francis Reddy

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Media Contact:

Claire Andreoli

301-286-1940

claire.andreoli@nasa.gov

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Share

Details

Related Terms

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

06Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly