Now Reading: Next stop, not Mars: What’s ahead for NASA’s newly launched ESCAPADE Red Planet probes

-

01

Next stop, not Mars: What’s ahead for NASA’s newly launched ESCAPADE Red Planet probes

Next stop, not Mars: What’s ahead for NASA’s newly launched ESCAPADE Red Planet probes

For the first time in more than five years, humanity has launched a mission to Mars — but it won’t be arriving at the Red Planet anytime soon.

NASA’s twin ESCAPADE probes launched Thursday (Nov. 13) on the second-ever flight of Blue Origin’s powerful New Glenn rocket. It was the first Mars liftoff since July 30, 2020, when NASA’s Perseverance rover and Ingenuity helicopter took flight atop an Atlas V rocket.

New Glenn sent the ESCAPADE pair not toward Mars, however, but to another deep-space destination — the sun-Earth Lagrange Point 2 (L2), a gravitationally stable spot about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from our planet.

That’s because Earth and Mars line up for efficient interplanetary flight just once every 26 months, and the next such window doesn’t open until late 2026. So, the ESCAPADE probes will hang out at L2 for 12 months, studying space weather in the region before looping back toward our planet in November 2026 for a speed-boosting “gravity assist” that will send them toward Mars.

ESCAPADE’s circuitous trajectory is novel and could aid further exploration of the Red Planet down the road, according to mission team members.

“Can we launch to Mars when the planets are not aligned? ESCAPADE is paving the way for that,” Jeffrey Parker of Advanced Space LLC, one of NASA’s partners on the $80 million mission, said at a conference earlier this year, according to an ESCAPADE explainer posted by the University of California, Berkeley on Nov. 5.

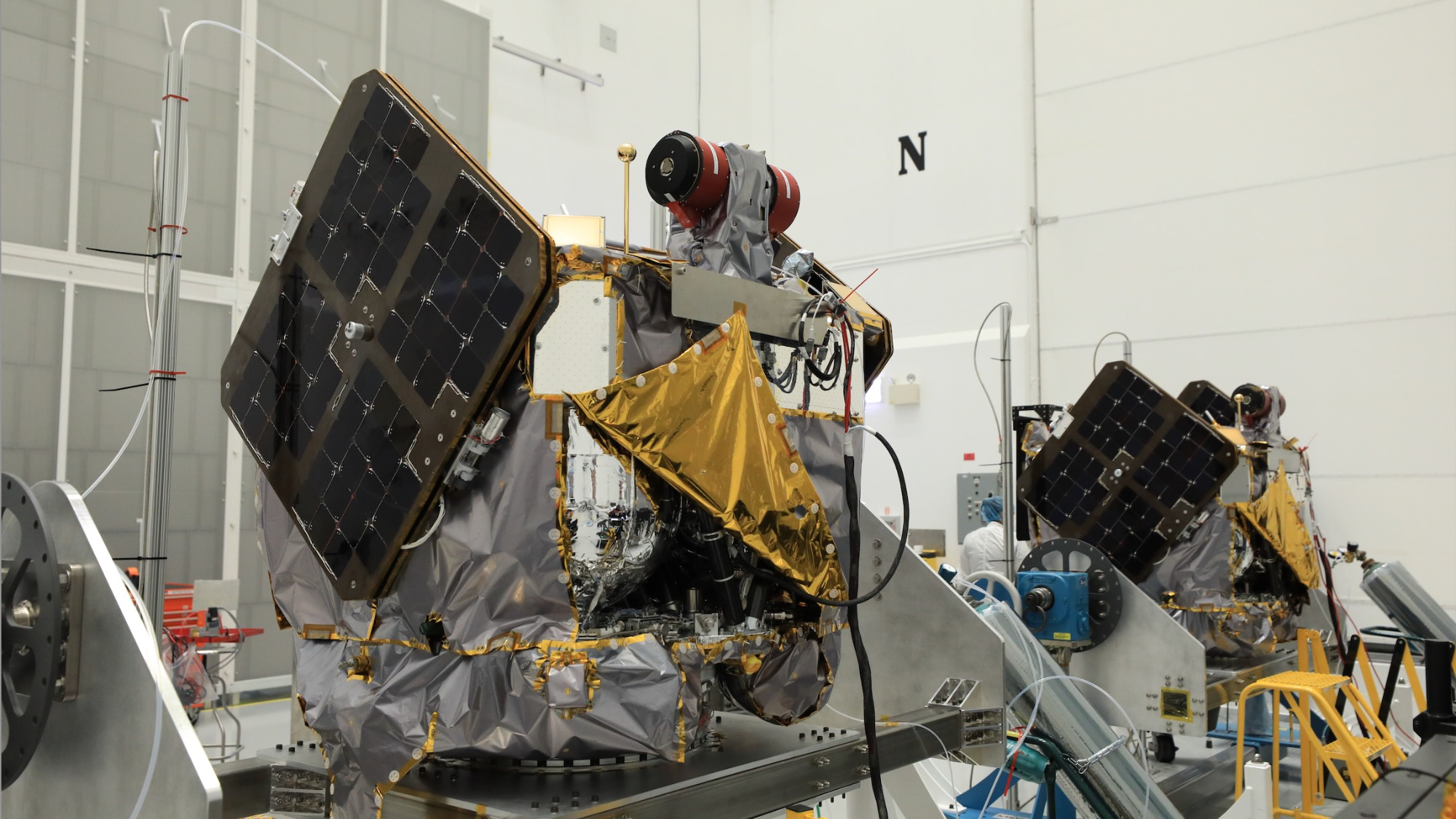

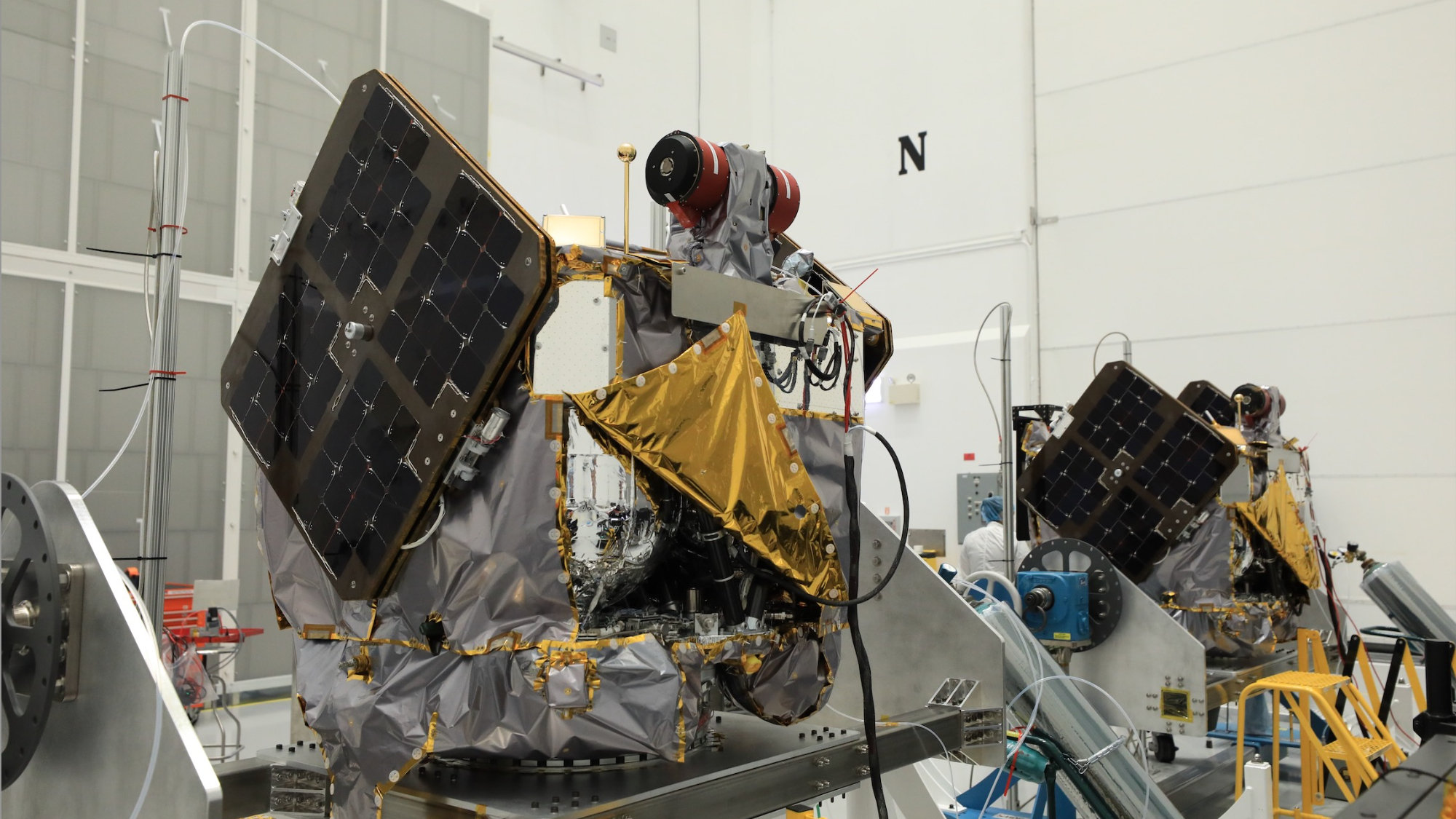

UC Berkeley is another partner: The university will manage and operate the ESCAPADE (“Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorer”) probes for NASA. In a nod to this fact, the twin spacecraft are named Blue and Gold, the university’s colors.

The trip to Mars from L2 will take about 10 months; Blue and Gold, which were built by the California company Rocket Lab, will arrive in Mars orbit in September 2027. They’ll then spend another seven months lowering and synchronizing their paths around the Red Planet, “so that they essentially are in the same orbit, following each other like a pair of pearls on a string,” ESCAPADE principal investigator Robert Lillis, of UC Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory, said in the explainer.

“That’s important scientifically because it lets us monitor the short timescale variability of the system. We don’t know what it is right now because the missions that have gone before, like MAVEN and Europe’s Mars Express, have had to wait until the following orbit, about four or five hours later, to see what conditions are like in a particular region,” Lillis added. “When we have two spacecraft crossing those regions in quick succession, we can monitor how those regions vary on timescales as short as two minutes and up to 30 minutes.”

Blue and Gold are both outfitted with the same science gear — a visible-light and infrared camera system, a magnetometer, an electrostatic analyzer and a Langmuir probe (which measures the properties of plasma).

Over the course of 11 months, they will use these instruments to map Mars’ upper atmosphere and magnetic fields, “providing the first stereo view of the Red Planet’s unique near-space environment,” UC Berkeley’s explainer reads. “What they find will help scientists understand how and when Mars lost its atmosphere and provide key information about conditions on the planet that could affect people who land or settle on Mars.”

Mission team members will have to be patient, as it’ll take a while for this data to come rolling in. But that shouldn’t be a problem; space scientists are used to playing the long game.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly