Now Reading: No more free rides: it’s time to pay for space safety

-

01

No more free rides: it’s time to pay for space safety

No more free rides: it’s time to pay for space safety

A small but important change can be found at the end of President Trump’s sweeping December 18, 2025, Executive Order, “Ensuring American Space Superiority.”

The Executive Order removes the requirement for the United States government to make basic space situational awareness data and space traffic management services available “free of direct user fees,” instead saying that such data should be available “for commercial and other relevant use.”

While this small change does not require satellite operators to pay for such data and services, it unlocks the opportunity for the U.S. government to directly or indirectly collect revenue to pay for space traffic management systems — revenue sorely needed to stabilize and improve U.S. space safety services as satellite activity rapidly grows.

The Department of Defense has provided spaceflight safety services to any interested satellite operator, free of charge, since the 2009 Iridium-Cosmos collision. The conventional wisdom in U.S. government policy circles — of which I was a part for many years — was that U.S. interests were well-served when domestic and foreign satellite operators used U.S. data and U.S. services, and that offering such services for free would increase adoption.

Those policy assumptions are no longer valid. While many foreign satellite operators have relied on free U.S. safety services in the past, there is no guarantee that they will in the future. Other countries see strategic value in operating their own space traffic coordination (STC) systems — strategic autonomy not just in maintaining a space industrial base but in keeping satellite operations themselves safe — meaning that despite well-intended policies, the U.S. government no longer has a monopoly on space situational awareness.

Furthermore, space situational awareness infrastructure is no longer just about safety services or even threat monitoring; it is the foundational digital layer that enables mission planning, operator training and real-time decision-making and coordination in a congested and contested domain; other countries are right to want sovereign space situational awareness infrastructure to meet their national needs.

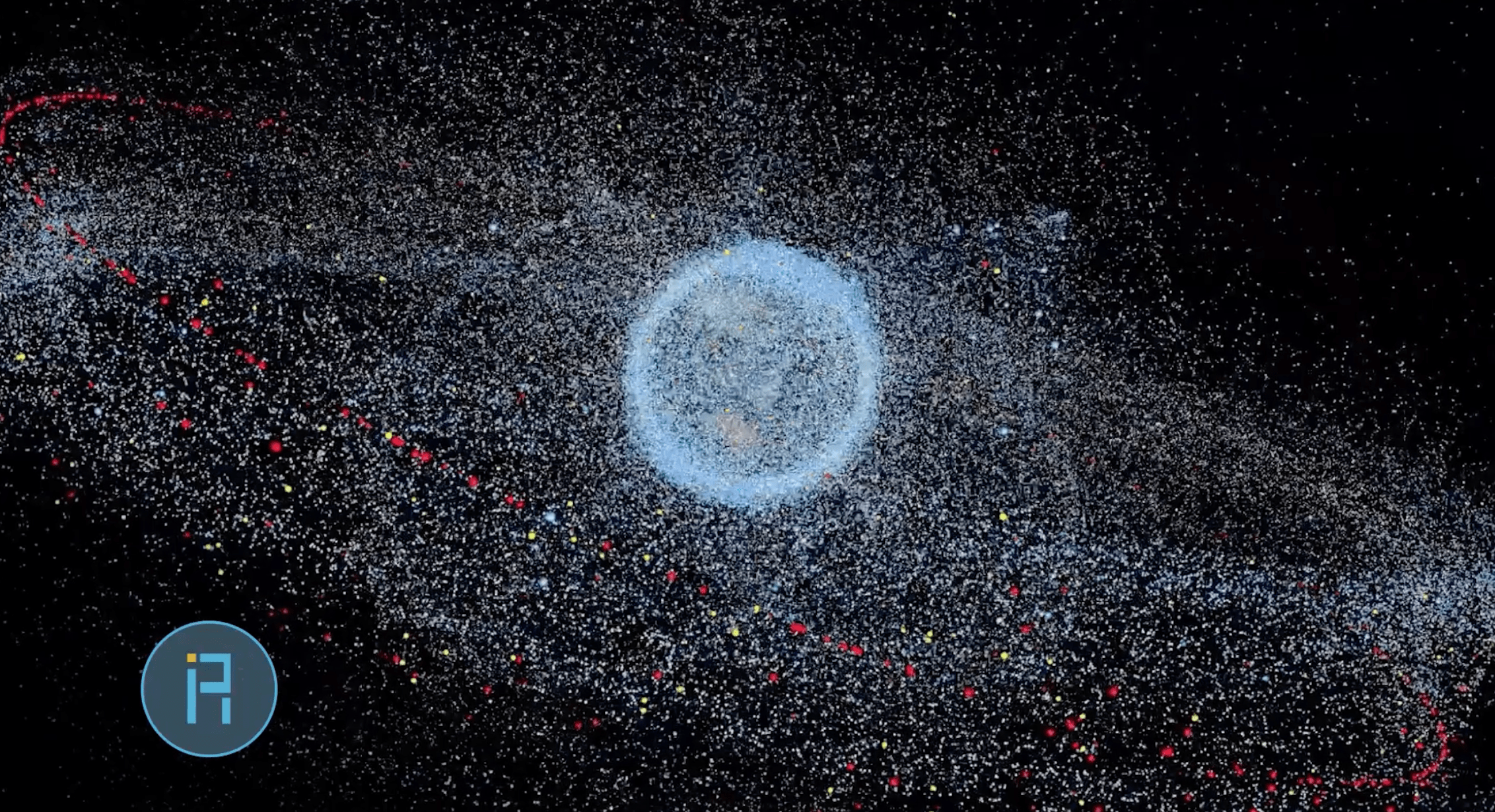

Continuing to leverage this infrastructure to provide free space traffic coordination services to any operator will become increasingly untenable as the number of satellites grows exponentially. In the intervening years since Iridium-Cosmos, the active satellite population has grown from a mere 1,000 to almost 14,000; the number of commercial satellite operators has risen from a few dozen to almost 200; and the number of conjunction data messages (the standard “close approach” notification) has exploded from just a few hundred per day to over 600,000.

We should all celebrate the meteoric rise of the U.S. space industry that is driving a busier and more dynamic space domain, while recognizing that part of its growth has been enabled by free government safety services. The job of identifying, assessing and preventing potential collisions in space — services beyond the more straightforward provision of data generated from U.S. government space situational awareness sensors — has literally become orders of magnitude more complex since the concept of space traffic management was in its infancy.

In its Fiscal Year 2026 budget request, the Trump Administration proposed eliminating the U.S. government’s space traffic coordination role and defunding the space equivalent of the U.S. air traffic control system — the Department of Commerce’s Traffic Coordination System for Space (TraCSS), which is expected to graduate from beta testing and “go live” with a full launch early this year. The administration argued that U.S. taxpayers should not bear the cost for space safety services and instead that commercial satellite operators should procure such services on the private market.

Wholly disestablishing a U.S. government civil space traffic coordination system just as TraCSS becomes operational is unwise, but making operators contribute to funding space safety services is smart and fiscally responsible policy.

Retaining a government role in STC

In the near-term, the U.S. government would be wise to keep TraCSS as its national space traffic coordination system and common information backbone for civil, commercial and national security space activities. TraCSS is already an operational capability that enables the U.S. to coordinate real-time spaceflight safety actions and negotiate international spaceflight standards with other governments that have set up similar national space traffic management systems — leading to a truly global “system of systems” for space traffic coordination.

Alternatives would, at best, fragment U.S. space traffic coordination services across multiple private companies or, at worst, continue to burden the Department of Defense with national responsibility for space safety — not exactly an inherently military function. Either alternative to TraCSS undercuts U.S. leadership on space traffic coordination, enabling other geopolitical actors like China or the European Union to step into the void, and ultimately does a disservice to the satellite operators trying to keep their fleets safe.

While there may be a longer-term path to privatize the U.S. space traffic coordination system, space safety information will remain a public good — meaning that the government should retain some role, whether that be regulatory oversight or standard-setting. The Federal Communications Commission’s recently proposed rule on “Space Modernization for the 21st Century” would take steps toward regulating in-orbit safety by requiring satellite operators to share real-time information on the location of their satellites and planned maneuvers. But this rule still implies that there is some centralized body receiving and redistributing such information among satellite operators.

While certainly this centralized body could be some form of public-private partnership where industry provides space traffic coordination services under the auspices of the government, this type of new organization would take time to establish.

In the interim, the U.S. must have an operational space traffic coordination system to protect the billions of dollars of investment in U.S. satellites already circling the globe. The TraCSS system, while not perfect, is available now to support U.S. satellite operators and should not be cast aside without a credible alternative — public or private.

But with projections of the satellite population growing to upwards of 100,000 by 2030, U.S. taxpayers cannot be expected to bear the full cost of operating TraCSS in the long-term. U.S. companies operating satellites have all raised significant amounts of capital to manufacture and launch their spacecraft — costs which are at historic lows but still top $1 million even when sharing a ride with over 100 other satellites. Given the permissive nature of the new Executive Order to allow for the collection of fees for space situational awareness data and space traffic coordination services, the U.S. government should look seriously at how best to supplestment taxpayer dollars with private revenue and help build and maintain a world-class space traffic coordination system.

A new model for funding STC

As part of the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” passed early in the Trump administration, Congress granted the FAA new authority to charge commercial space companies per pound of payload mass put into orbit. Led by Senator Cruz, who noted that the rising number of space launches is adding strain to the national airspace system, the new authority will allow the FAA to collect revenue from launch providers, who presumably will pass those fees along to their satellite operator customers. That revenue can then be applied to upgrading the national airspace system to better manage the increasing cadence of commercial space launch. This is an excellent first step at cost-sharing with the space industry but only addresses congestion in the airspace — not on orbit.

Congress’s next step should be to create a similar “space traffic” financing authority that allows the executive branch to collect taxes or fees from satellite operators. The revenue generated from such fees would create a steady stream of funding for space safety services that scales with the growing satellite population.

As one hypothetical example of how such fees could be structured, requiring satellite operators to pay just $1,000 annually per satellite they operate in orbit (far less than what they already pay in annual regulatory fees for spectrum allocation) would fund 25% of the roughly $55 million appropriated for TraCSS last year — a reasonable cost-sharing starting point. Alternatively, a fraction of the fees that FAA will collect from launch providers could be apportioned to fund TraCSS.

New authority for the Department of Commerce to collect fees could be part and parcel of a new “mission authorization” authority, under consideration now for several years, that would grant Commerce broad authority to license and oversee a wide range of U.S. satellite operations — updating and providing much needed predictability to the U.S. space regulatory system. Such fees don’t need to be tied directly to the provision of space safety services but could instead be linked to processing license applications and could vary based on the complexity or scale of the mission being authorized.

Skeptics will say that putting additional requirements (especially monetary ones) on satellite operators will be too much of a burden on U.S. industry. This risk can be mitigated by continuing some level of appropriated funding to keep fees low, especially during the transition period.

Another concern is that forcing U.S. satellite operators to pay into — and use — the U.S. system will drive U.S. space companies to “re-flag” overseas where such services are provided for free by other governments. In this case, the U.S. government can and should ensure that its space traffic coordination system is the best in the world — an achievable goal if the U.S. government leverages the industry-leading space tracking, analytic and predictive solutions already available from U.S. space situational awareness companies. And if this “carrot” proves ineffective, a more draconian approach would be to make eligibility for U.S. government contracts contingent upon receiving a U.S. mission authorization license — something previously contemplated but not U.S. policy today.

This model of cost-sharing for safety services is not without precedent. Over 80% of the annual operating funds for the U.S. air traffic control system is financed through taxes and fees paid by air travelers and airlines. But satellite operators pay no such equivalent fees to keep their revenue-generating assets safe in orbit. The Trump administration is right to try and address this disconnect.

Stable, long-term funding is needed to bring together disparate proprietary space situational awareness capabilities into a fully integrated, continuously operating world-class space traffic coordination system — funding that need not come exclusively from taxpayer dollars. Now is the time to establish a sensible government-industry partnership to fund and operate a world-class U.S. space traffic coordination system — the digital backbone for safe operations, responsible growth, and U.S. leadership in space.

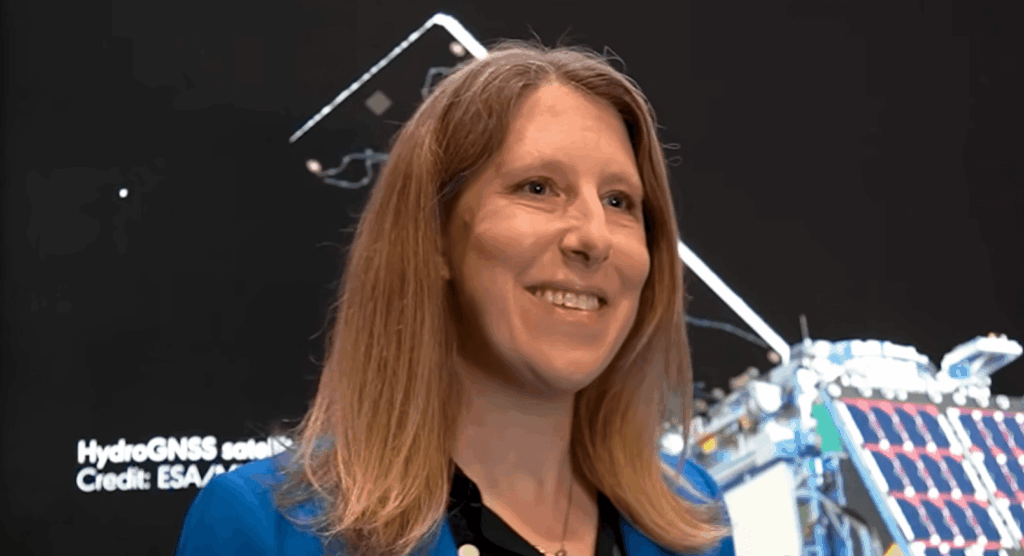

Audrey M. Schaffer is the Senior Vice President of Global Policy and Government Strategy at Slingshot Aerospace, which aims to accelerate space safety, sustainability and security by transforming how data about the space domain is collected, fused, analyzed and used in real-time decision making. She previously served for over 15 years as a U.S. government civil servant responsible for space policy.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion (at) spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. If you have something to submit, read some of our recent opinion articles and our submission guidelines to get a sense of what we’re looking for. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent their employers or professional affiliations.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly