Now Reading: Proximity to a supermassive black hole doesn’t spell doom

-

01

Proximity to a supermassive black hole doesn’t spell doom

Proximity to a supermassive black hole doesn’t spell doom

EarthSky’s 2026 Lunar Calendar is available now. Get yours today! Makes a great gift.

Snuggling up to our galaxy’s supermassive black hole

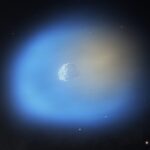

For years, astronomers have been keeping a close eye on the supermassive black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy, named Sagittarius A* (pronounced Sagittarius A-star), or Sgr A* for short.

It’s long been thought that objects in extremely close proximity to this supermassive black hole would be pulled into its powerful gravitational well. For example, a sunlike star closer than the distance of Mercury’s orbit around our sun – far less than Earth’s distance from the sun – would be swallowed by the black hole and ultimately torn apart. Now scientists from the University of Cologne have performed a new study on some of the closest objects we know, in orbit around Sgr A*. They pointed out on November 28, 2025, that these objects, though close to the supermassive black hole, aren’t close enough to be shredded by its powerful gravity. Plus, they now believe the most famous of these objects – called G2 – isn’t a dust cloud, as originally thought. Instead, G2 is likely more starlike, perhaps with dusty outer layers.

So they found that orbiting close to a black hole is not a death sentence. Instead, if objects are far enough away, they can maintain stable orbits around a supermassive black hole.

The international team of astronomers, led by Florian Peissker at the University of Cologne, published its peer-reviewed paper in the December 2025 issue of Astronomy & Astrophysics.

How close to Sagittarius A*?

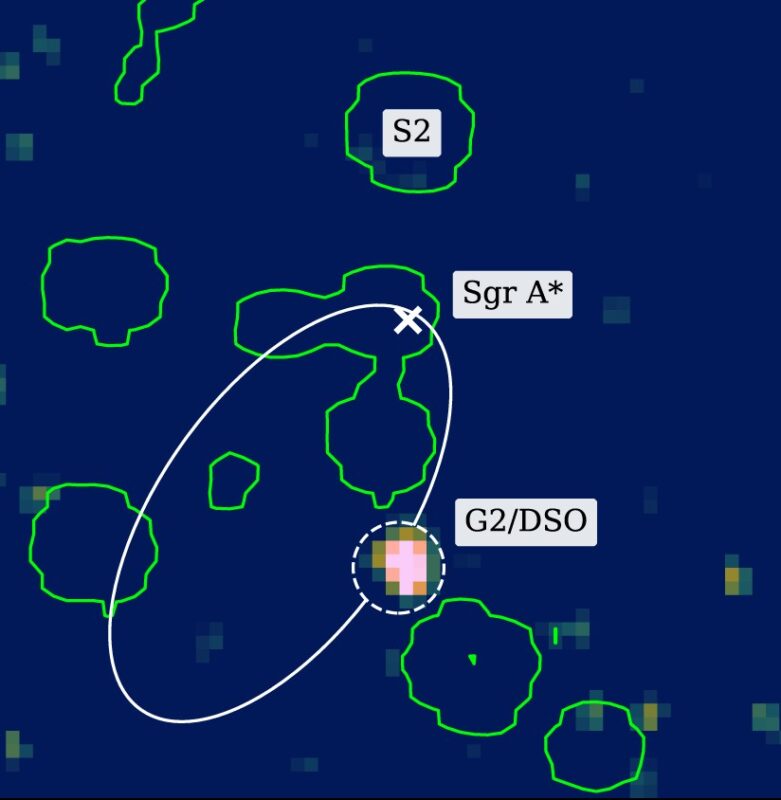

The astronomers used the Enhanced Resolution Imager and Spectrograph (ERIS) at the Very Large Telescope (VLT) facility in Chile to monitor activity around Sagittarius A*. They focused on a few objects in particular, all belonging to what they call the “S-cluster,” a dense group of young, high-velocity stars orbiting Sgr A*.

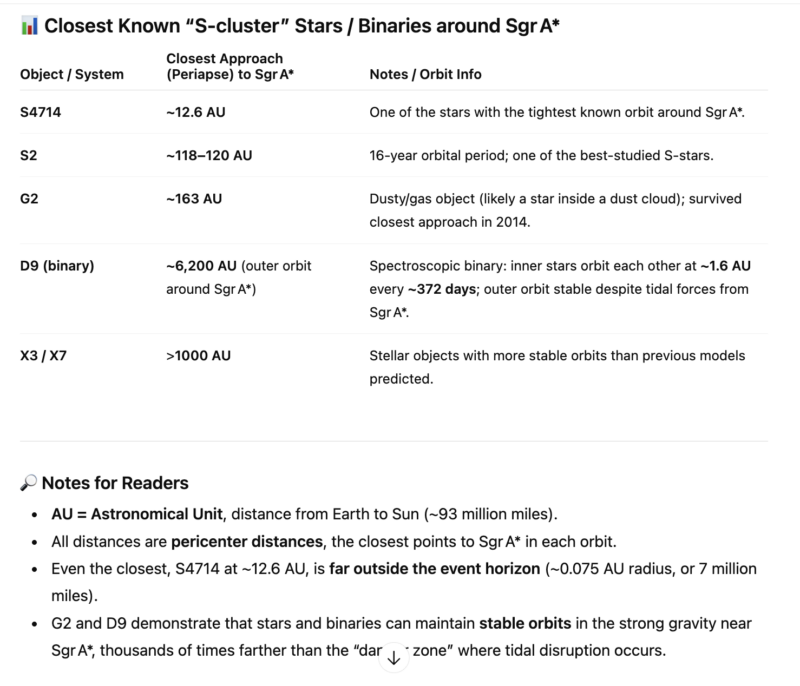

One object they studied was G2, which astronomers had long suspected was a large gas and dust cloud. G2 made headlines about a decade ago when it survived its closest passage by the supermassive black hole and continued on its elliptical orbit. It came within about 163 astronomical units (AU) – about 100 to 200 times the Earth-sun distance – from Sgr A*. These observations, and more since, indicate a star inside a dust cloud.

The team also looked at D9, a binary star system discovered in 2024. Despite its proximity to the violent tidal forces of the nearby black hole, D9 remains in a stable orbit. The inner binary – two stars orbiting each other with a separation of ~1.6 AU and period ~372 days – remains tightly bound to each other, easily resisting tidal forces from Sgr A*. Thus, although D9 is “close” to Sgr A* in the sense of being within the dense star cluster at the galactic center, it’s far outside the zone of destruction.

What’s more, the nearby gravitational force from Sgr A* hasn’t nudged the D9 stars into colliding and forming one massive star.

In addition, the team monitored stellar objects X3 and X7. These stars also have more stable orbits than previous models predicted.

The following is a table of some of the closest known “S-cluster,” stars / binaries with their periapse distances (a periapsis, or pericenter, is the point in an orbit where a celestial body is closest to the central body it is orbiting).

Violence versus stability

Lead author Peissker said:

The fact that these objects move in such a stable manner so close to a black hole is fascinating. Our results show that Sagittarius A* is less destructive than was previously thought. This makes the center of our galaxy an ideal laboratory for studying the interactions between black holes and stars.

Co-author Michal Zajacek from Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic, added:

The supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way has not only the capability to destroy stars, but it can also stimulate their formation or the formation of pretty exotic dusty objects, most likely via mergers of stellar binaries.

How close to a supermassive black hole is safe?

The astronomers plan to make more observations with ERIS and the upcoming Extremely Large Telescope. They hope to track the evolution of these objects and understand how stars survive in such close proximity to a supermassive black hole.

To give a sense of the extreme danger near Sgr A*, Naoufal Souitat of the Southwest Research Institute calculated that an object skimming just a million miles above the black hole’s event horizon would need to travel nearly 600,000 miles per hour (nearly 1,000,000 kph) to avoid being pulled in. That’s only slightly faster than the sun’s orbit around the Milky Way. In reality, the objects studied, like G2 and the binary D9, stay thousands of times farther out – tens to thousands of astronomical units (AU) away – safely beyond the black hole’s “death zone.” Their survival shows that proximity to a supermassive black hole does not automatically mean destruction; stars and star-like systems can maintain stable, enduring orbits even in the heart of our galaxy.

Bottom line: Scientists studied stars in the “S-cluster,” a dense group of young, high-velocity stars orbiting our galaxy’s central supermassive black hole. They found these stars in stable orbits.

Source: Closing the gap: Follow-up observations of peculiar dusty objects close to Sgr A* using ERIS

The post Proximity to a supermassive black hole doesn’t spell doom first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly