Now Reading: Saturn-mass rogue planet revealed in unique new observations

-

01

Saturn-mass rogue planet revealed in unique new observations

Saturn-mass rogue planet revealed in unique new observations

- Rogue planets, or free-floating planets, are planets that don’t orbit stars. Instead, they drift alone through space.

- Astronomers have found a new rogue planet, using instruments both on Earth and in space at the same time. This is the first such detection of its kind, and the first confirmed mass of a rogue planet.

- The planet has a mass similar to Saturn and is located about 9,800 light-years from us, toward the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

EarthSky’s 2026 lunar calendar is available now. Get yours today! Makes a great gift.

A newly discovered Saturn-mass rogue planet

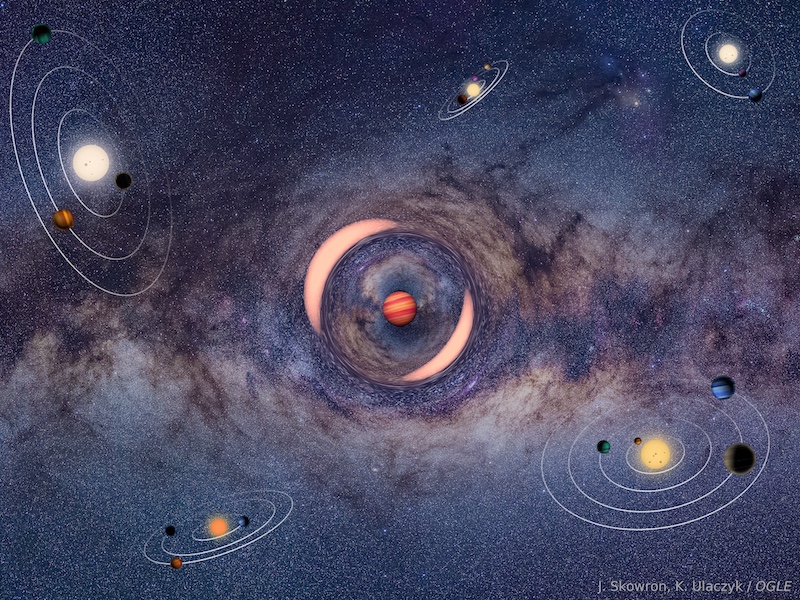

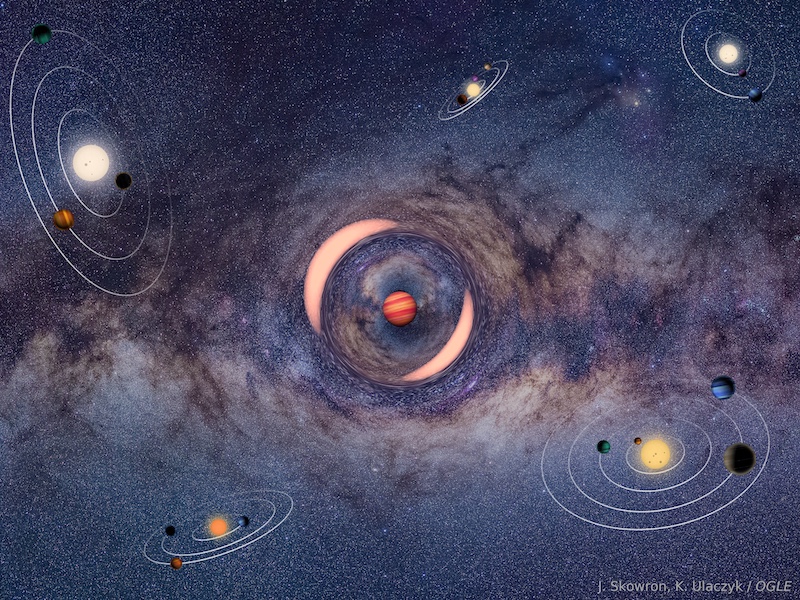

An international team of astronomers said on January 2, 2026, that they discovered a new rogue – or free-floating – planet drifting among the stars. It has a mass similar to Saturn and resides about 9,800 light-years from us, in the direction of the center of the Milky Way. Notably, this is the first rogue planet where astronomers have used observatories both on Earth and in space at the same time to make the detection. In addition, it is also the first time that astronomers have directly measured the mass of a rogue planet.

Subo Dong at Peking University in China led the research team that made the discovery.

Such rogue planets float freely by themselves in space, with no stars to orbit. In fact, astronomers have been discovering a growing number of these worlds in recent years, and expect to find many more.

The researchers published their peer-reviewed findings in the journal Science on January 1, 2026. There is also a non-paywalled preprint version of the paper available on arXiv.

In addition, there is a related new Perspective article in Science, also published on January 1, 2026, to go along with the new paper.

Featured in the first issue of Science in 2026, a research team led by Dong Subo of #PekingUniversity reported the first accurate mass measurement of a rogue planet candidate, confirming its planetary nature with a mass comparable to that of Saturn.www.science.org/doi/10.1126/…@science.org

— Peking University (@pku1898.bsky.social) 2026-01-02T04:05:45.415Z

2 views of a Saturn-mass rogue planet

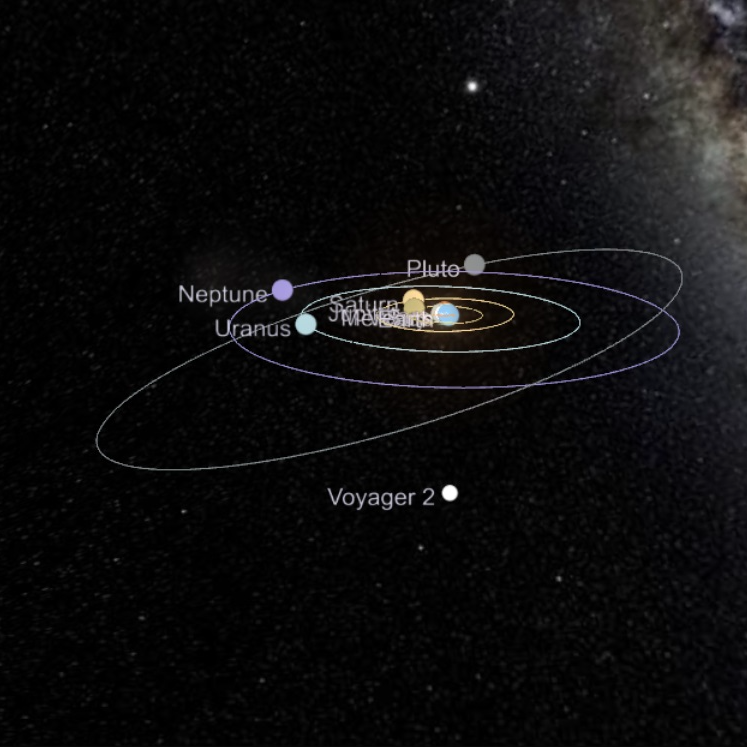

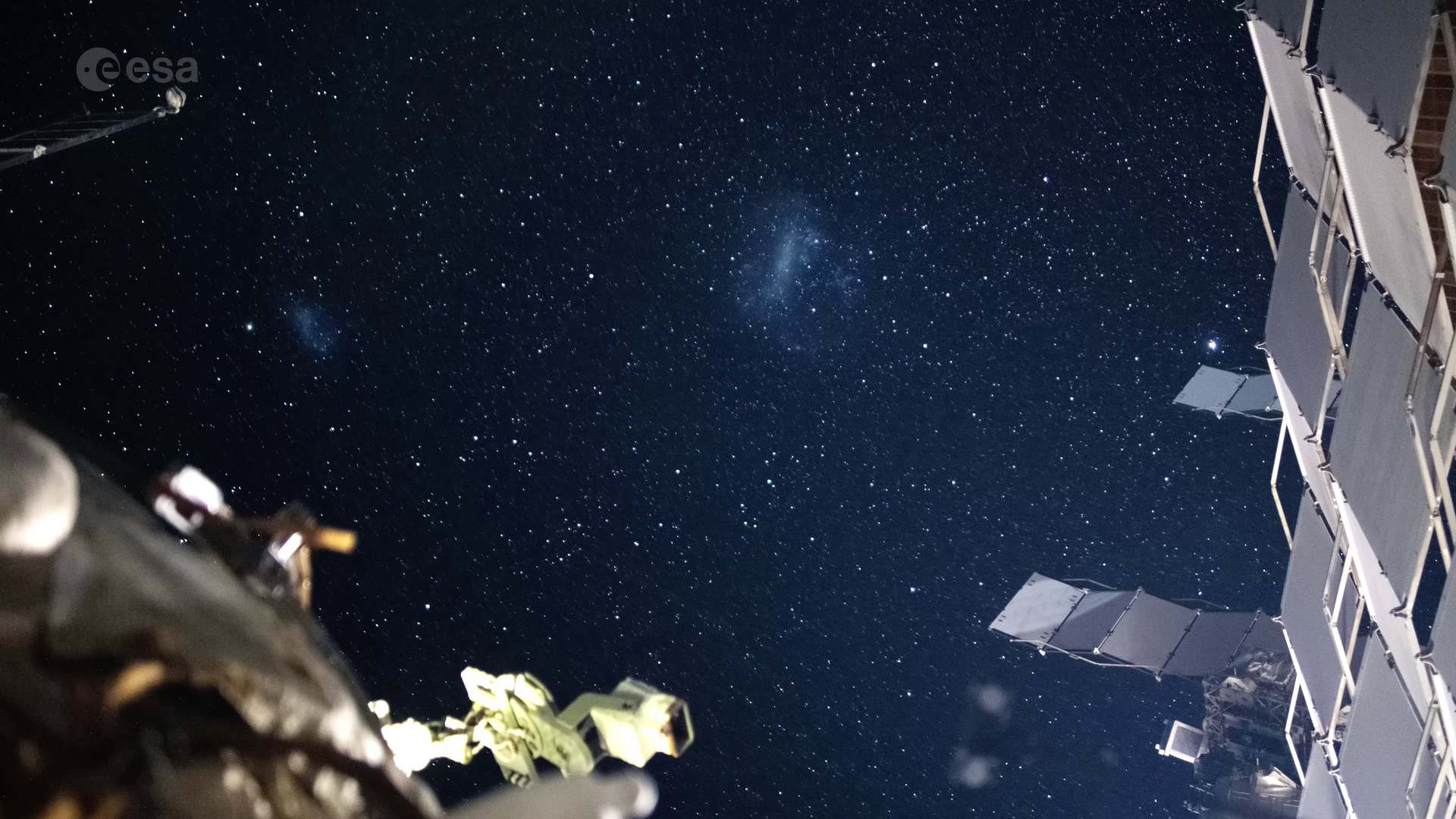

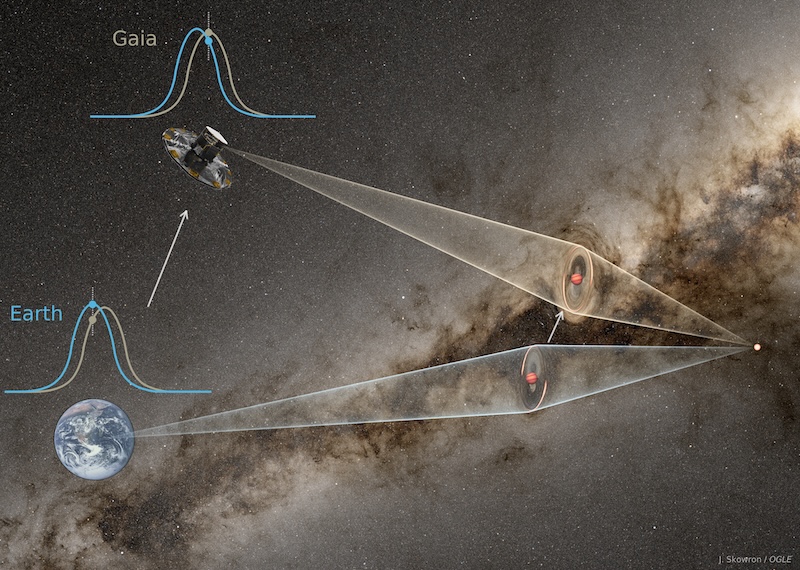

While astronomers have detected a growing number of rogue planets, these new observations were unique. That’s because the researchers made the detection using instruments both on Earth and in space. This included several ground-based surveys and data from ESA’s Gaia space telescope (which ended its mission in January 2025).

It’s the first time astronomers have identified a rogue planet using both types of observations. Additionally, it’s also the first direct measurement of a rogue planet’s mass. Dong said:

For the first time, we have a direct measurement of a rogue planet candidate’s mass and not just a rough statistical estimate. We know for sure it’s a planet. Our discovery offers further evidence that the galaxy may be teeming with rogue planets that were likely ejected from their original homes.

Dong added:

We are able to use the same principle to extract the distance information of this rogue planet candidate, finding the mass and distance separately. You need to have this fundamental measurement of mass to really know it’s a planet. Getting this kind of data opens up lots of doors to understanding more about a planet’s possible origins and history.

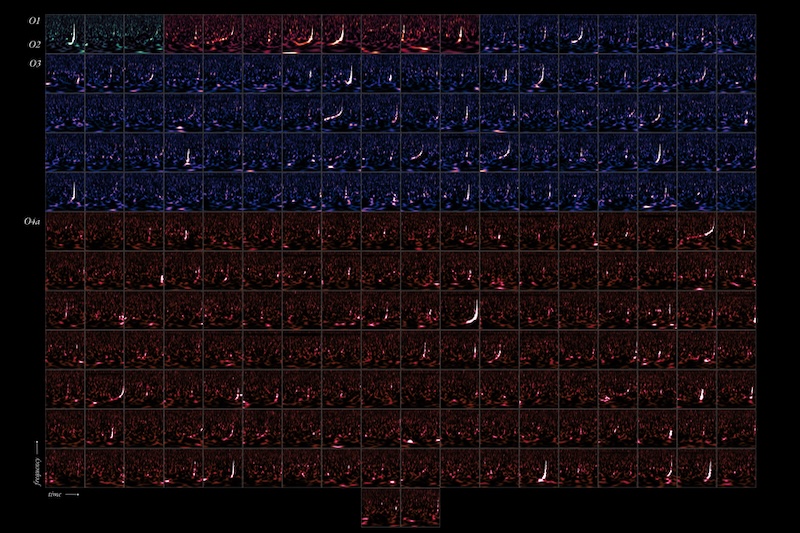

Animation depicting the microlensing event caused by the Saturn-mass rogue planet. Video via J. Skowron/ OGLE/ Peking University.

Free-floating planet microlensing event

So, how exactly did the research team find the planet? They used a technique called microlensing (or gravitational lensing). Basically, the gravity of the rogue planet microlenses – or magnifies – the light of a more distant background star. The researchers dubbed this microlensing event as KMT-2024-BLG-0792/OGLE-2024-BLG-0516. (How’s that for a mouthful?)

In this case, the researchers were able to observe the microlensing effect using both the ground surveys and data from the Gaia space telescope. The tiny differences in timing of when the light from the microlensing event reached the various instruments allowed the researchers to measure the microlensing parallax (the apparent shift in an object’s position when viewed from different locations).

Then, the researchers combined the data with finite-source point-lens modeling. Consequently, this revealed the mass and location of the planet.

The planet is closer to the middle of the Milky Way than we are. It is about 9,800 light-years (3,000 parsecs) from us, toward the center of our galaxy.

Ejected from a planetary system

Some rogue planets might have formed where they are, without ever having orbited any star. This one, however, likely was once in a planetary system around a star and then somehow got ejected into interstellar space. This could happen through gravitational interactions with other planets in the system or the instability of other stellar companions to the star. The paper states:

Through comparison with the statistical properties of other observed microlensing events and predictions from simulations, we infer that this object likely formed in a protoplanetary disk (like a planet), not in isolation (like a brown dwarf), and dynamical processes then ejected it from its birth place, producing a free-floating object.

Many more rogue planets out there

Rogue planets are difficult to find because they don’t orbit stars and are therefore shrouded in darkness. But astronomers have been discovering a growing number of these odd, isolated worlds. As of now, there are a few dozen confirmed and candidate rogue planets. And scientists said there might be billions or even trillions of them in our galaxy alone. In fact, there might even be more rogue planets than “regular” planets that orbit stars!

Scientists expect the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope – scheduled to launch by May 2027 – will discover at least 400 more. It will be exciting to see what it finds! As Dong noted:

The new space-based facilities such as Roman, CSST and Earth 2.0 are going to revolutionize the field of microlensing and the study of free-floating planets. So far, we only have a glimpse into this emerging population of rogue worlds and what light they can shed on the formation of the bodies in the planetary systems of the universe.

Bottom line: Astronomers have discovered a Saturn-mass rogue planet nearly 10,000 light-years away. It’s the first one found using both observatories on Earth and in space.

Sources:

A free-floating-planet microlensing event caused by a Saturn-mass object

(Preprint): A free-floating-planet microlensing event caused by a Saturn-mass object

Via:

Read more:

Giant free-floating planets might have planets of their own

Could homeless aliens hitch a ride on rogue planets?

The post Saturn-mass rogue planet revealed in unique new observations first appeared on EarthSky.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly