Now Reading: Scientists discover bizarre double-star system with exoplanet on a sideways orbit (video)

-

01

Scientists discover bizarre double-star system with exoplanet on a sideways orbit (video)

Scientists discover bizarre double-star system with exoplanet on a sideways orbit (video)

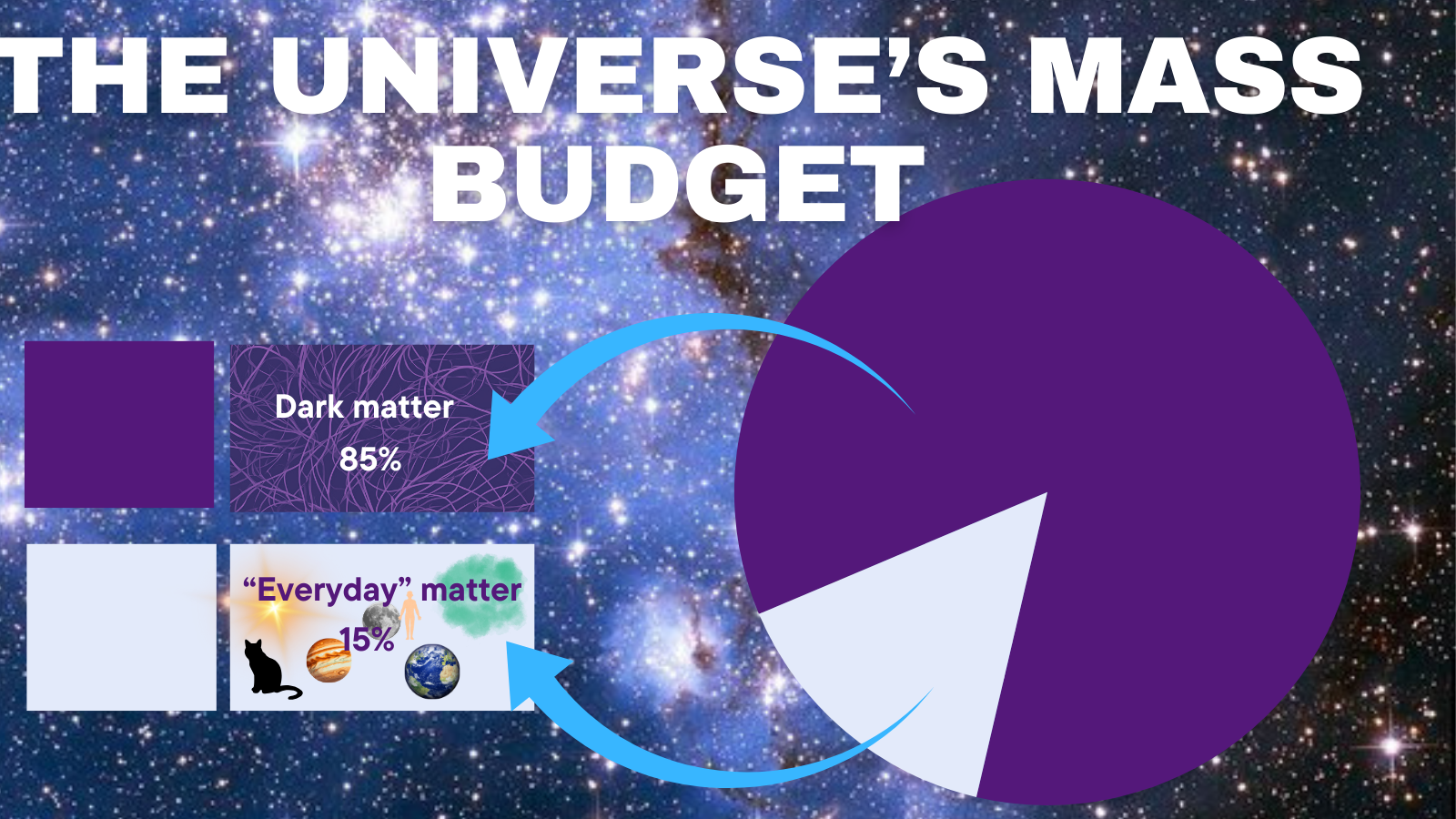

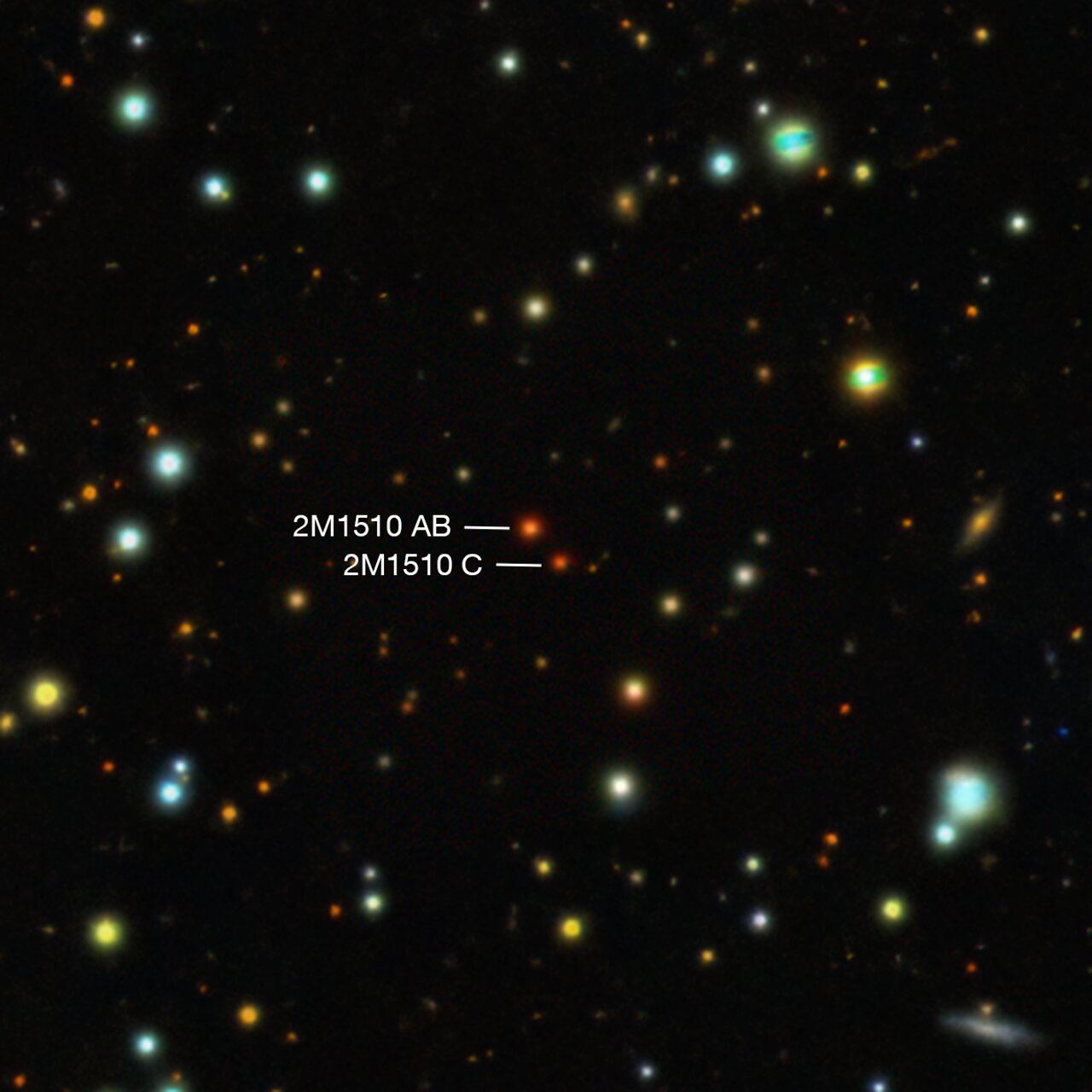

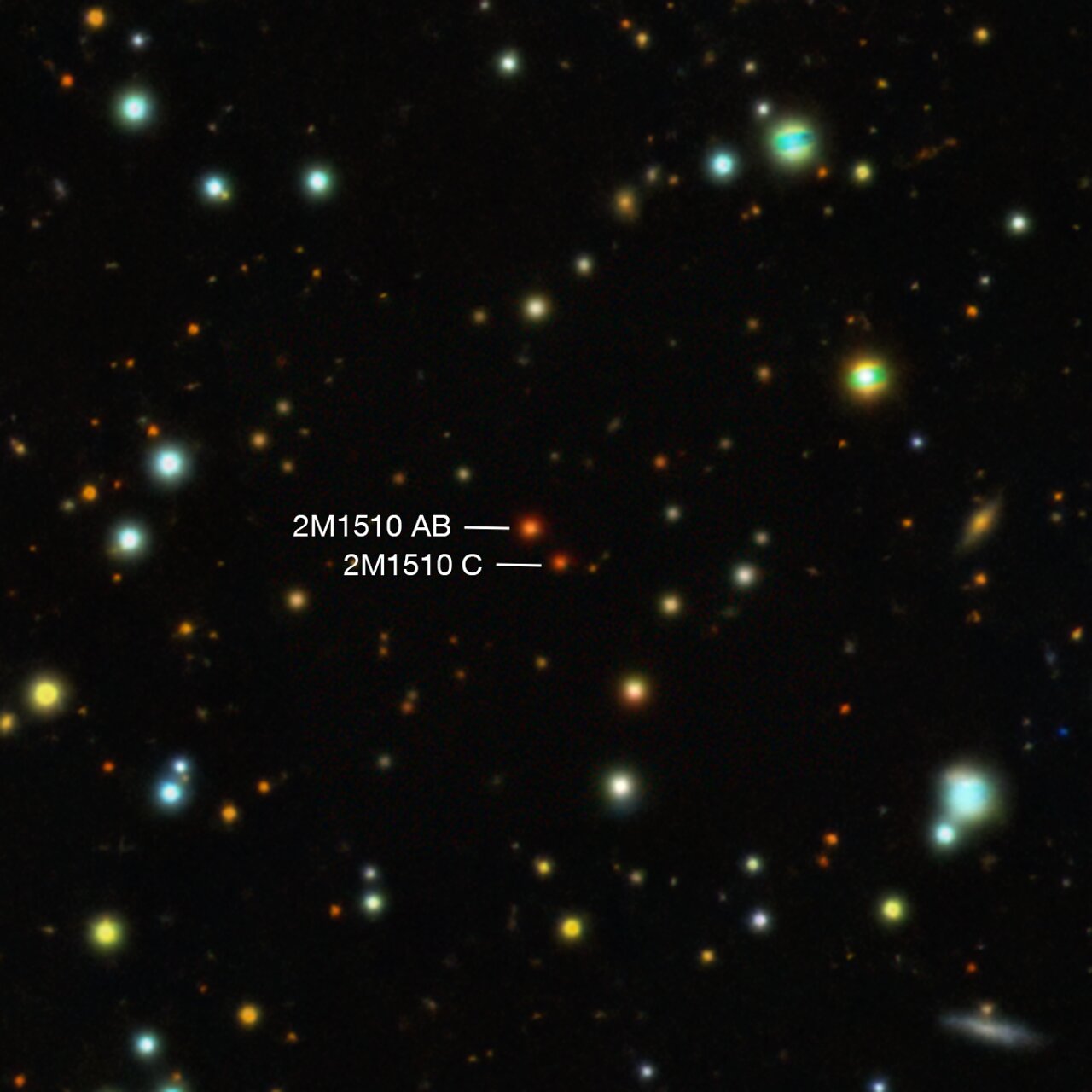

Scientists have perhaps discovered the weirdest planetary system ever seen. Not only does this system feature the first-ever “polar planet” to be discovered, meaning the world exists on a sideways orbit, but that planet also circles around two stars. But that’s not all — those parent stellar bodies are also brown dwarfs, better known as “failed stars.”

Since astronomers started discovering extrasolar planets, or “exoplanets,” in the mid-1990s, worlds orbiting other stars have demonstrated that, compared to our somewhat mundane solar system, the universe is a pretty wild place.

Exoplanet hunters have found strange worlds unlike anything we see in the solar system, including worlds so light they can be compared to marshmallows, worlds so hot they rain liquid metal or glass, and now, a world that weirdly orbits its stars at a 90-degree angle.

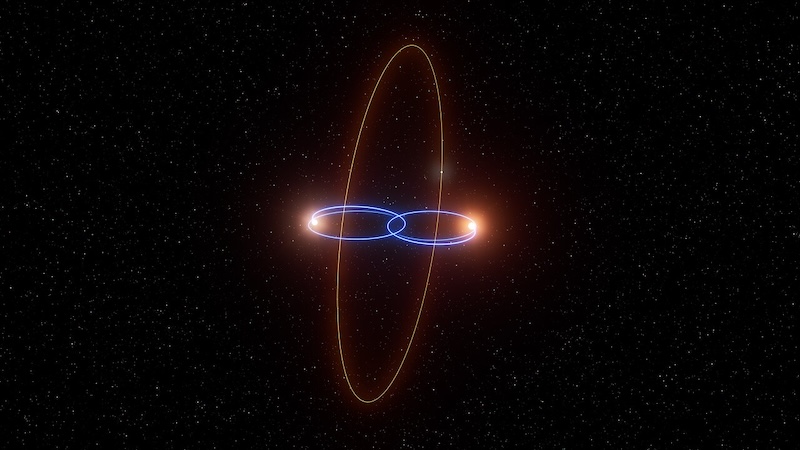

However, while we’ve discovered plenty of planets orbiting binary stars before, evocative of the two-star planet Tatooine in the Star Wars franchise, astronomers have never seen an exoplanet rolling around a binary pairing at 90 degrees to the orbital plane of those stars — until now, that is.

The exoplanet 2M1510 (AB) b is located around 120 light-years away in the constellation of Libra.

Scientists had previously seen hints that planets could exist in polar orbits around binary stars, for instance finding planet-forming protoplanetary disks around twin stars. However, this is the first solid evidence of such a fully formed system.

“I am particularly excited to be involved in detecting credible evidence that this configuration exists,” team leader Thomas Baycroft of the University of Birmingham said in a statement.

Stranger and stranger

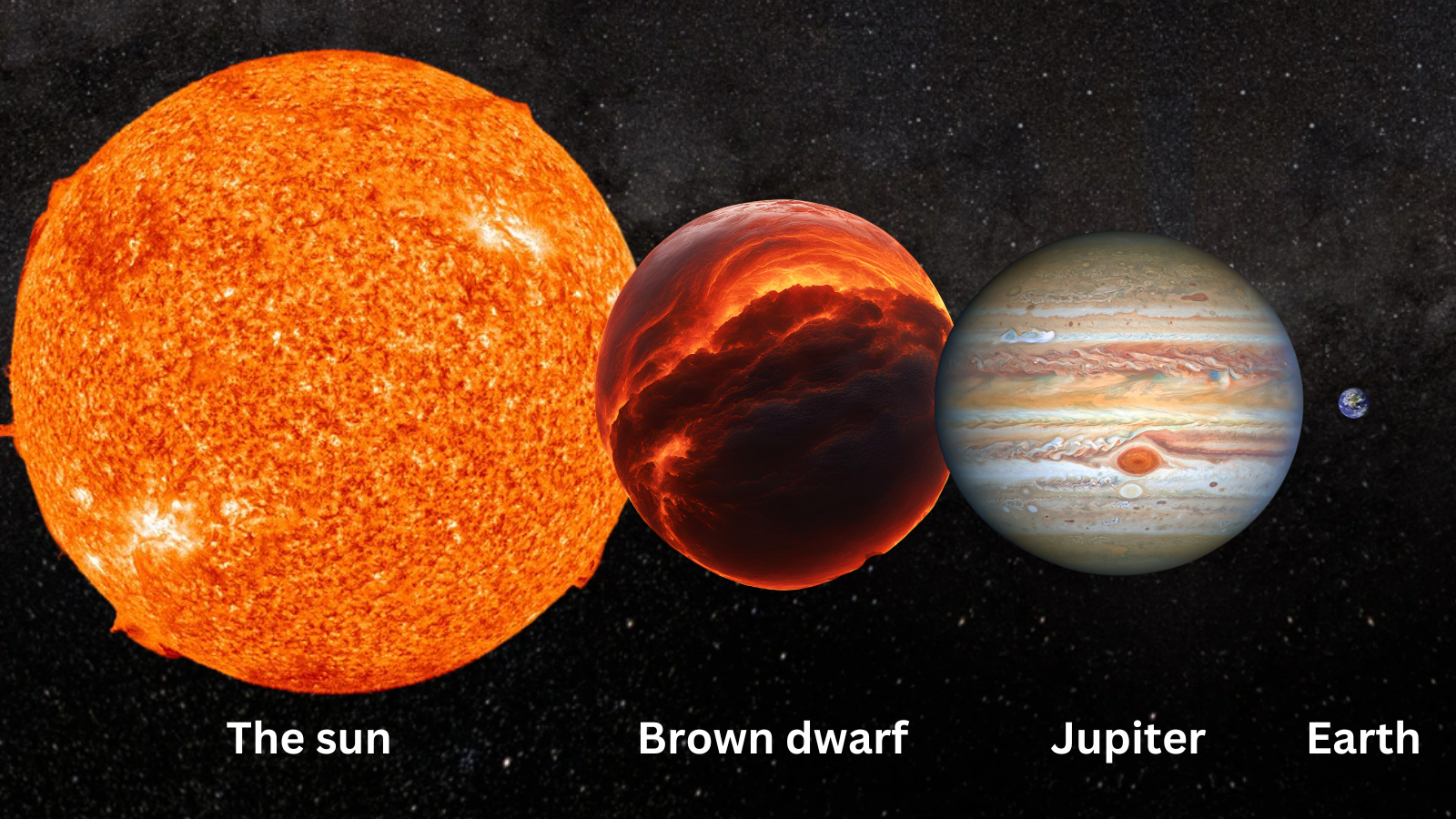

As mentioned, however, this system gets even stranger because the parent bodies of exoplanet 2M1510 (AB) b — 2M1510 AB and 2M1510 C — are brown dwarfs. Brown dwarfs are stellar bodies that get their unfortunate nickname of “failed stars” because, though they are born from collapsing clouds of gas and dust like standard stars, they fail to gather enough matter to achieve the mass needed to trigger the fusion of hydrogen to helium in their cores, the process that defines what a star is.

Furthermore, the chance of stellar bodies having a binary partner increases with mass, making a double-brown-dwarf star system pretty surprising.

Around 75% of stars with masses around 10 times that of the sun are in binaries, and around 50% of sun-like stars have a partner. With masses between 0.075 and 0.013 times that of the sun (or 75 to 13 times that of Jupiter), brown dwarfs in binaries are very rare.

Further adding to the strangeness of this system (how much weirder can it get?), this is only the second pair of eclipsing brown dwarfs ever discovered. This means one of the brown dwarfs eclipses the other, as seen from our vantage point on Earth.

“A planet orbiting not just a binary, but a binary brown dwarf, as well as being on a polar orbit, is rather incredible and exciting,” team member Amaury Triaud of the University of Birmingham said in the statement.

Triaud has a history with these failed stars, being part of the team that discovered them in 2018 using the Search for Habitable Planets Eclipsing Ultra-cool Stars (SPECULOOS) at Paranal Observatory in Chile.

The current team discovered the weird polar planet while attempting to better understand the orbits of the two brown dwarfs in this system using the Ultraviolet and Visual Echelle Spectrograph (UVES) instrument attached to the Very Large Telescope (VLT), also located at the Paranal Observatory.

This observation program revealed that the failed stars are being “pushed and pulled” by the gravitational influence of an unseen planet. The strange dynamics of this action led the researchers to conclude that this world is a polar planet with a 90-degree orbit.

“We reviewed all possible scenarios, and the only one consistent with the data is if a planet is on a polar orbit about this binary,” Baycroft said.

Related Stories:

“The discovery was serendipitous, in the sense that our observations were not collected to seek such a planet, or orbital configuration. As such, it is a big surprise,” Triaud concluded. “Overall, I think this shows to us astronomers, but also to the public at large, what is possible in the fascinating universe we inhabit.”

The team’s research was published on Wednesday (April 16) in the journal Science Advances.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

04Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

05Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

06True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors

07Thermodynamic Constraints On The Citric Acid Cycle And Related Reactions In Ocean World Interiors