Now Reading: Scientists use James Webb Space Telescope to make 1st 3D map of exoplanet — and it’s so hot, it rips apart water

-

01

Scientists use James Webb Space Telescope to make 1st 3D map of exoplanet — and it’s so hot, it rips apart water

Scientists use James Webb Space Telescope to make 1st 3D map of exoplanet — and it’s so hot, it rips apart water

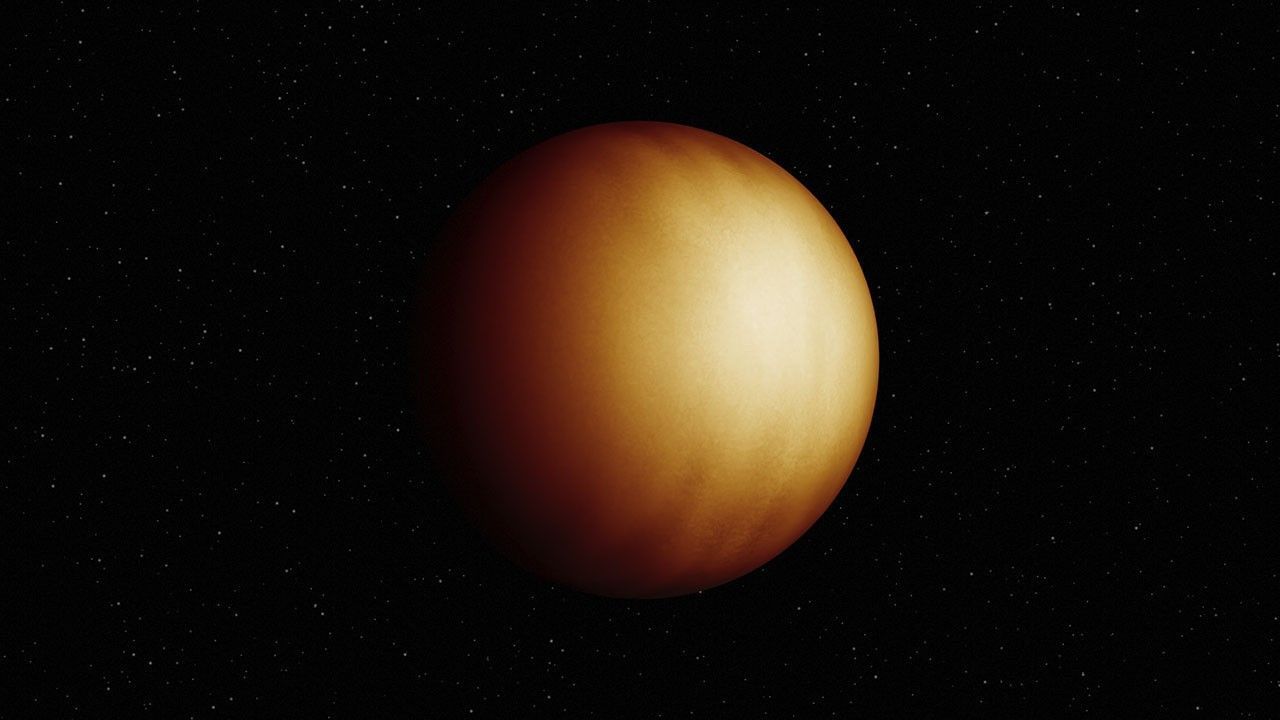

Astronomers have produced the first-ever three-dimensional map of a planet outside our solar system — WASP-18b — marking a major leap forward in exoplanet research.

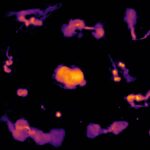

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, researchers applied a new technique called 3D eclipse mapping, or spectroscopic eclipse mapping, to track subtle changes in various light wavelengths as WASP-18b moved behind its star. These variations allowed scientists to reconstruct temperature across latitudes, longitudes and altitudes, revealing distinct temperature zones throughout the planet’s atmosphere.

“If you build a map at a wavelength that water absorbs, you’ll see the water deck in the atmosphere, whereas a wavelength that water does not absorb will probe deeper,” Ryan Challener, a postdoctoral associate in Cornell’s Department of Astronomy and lead author of a study published on the research, said in a statement. “If you put those together, you can get a 3D map of the temperatures in this atmosphere.”

WASP-18b is located about 400 light-years from Earth; it has roughly 10 times Jupiter’s mass and completes an orbit of its host star in just 23 hours. Because it’s so close to its star, temperatures in the planet’s atmosphere reach nearly 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,760 degrees Celsius). Those scorching conditions made it an ideal candidate for testing the new method of 3D temperature mapping.

The map revealed a bright central hotspot surrounded by a cooler ring on the planet’s dayside — it has a tidally locked orbit, meaning that one side of the planet is always facing its star — demonstrating that the exoplanet’s winds fail to distribute heat evenly across the atmosphere.

Remarkably, the hotspot showed lower water vapor levels than WASP-18b’s atmospheric average. “We think that’s evidence that the planet is so hot in this region that it’s starting to break down the water,” Challener said. “That had been predicted by theory, but it’s really exciting to actually see this with real observations.”

This new 3D eclipse mapping technique will open many doors in exoplanet observations, as it “allows us to image exoplanets that we can’t see directly, because their host stars are too bright,” said Challener. As 3D eclipse mapping is applied to other exoplanets observed by Webb, “[w]e can start to understand exoplanets in 3D as a population, which is very exciting,” he added.

The team’s research was published in the journal Nature Astronomy on October 28, 2025.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

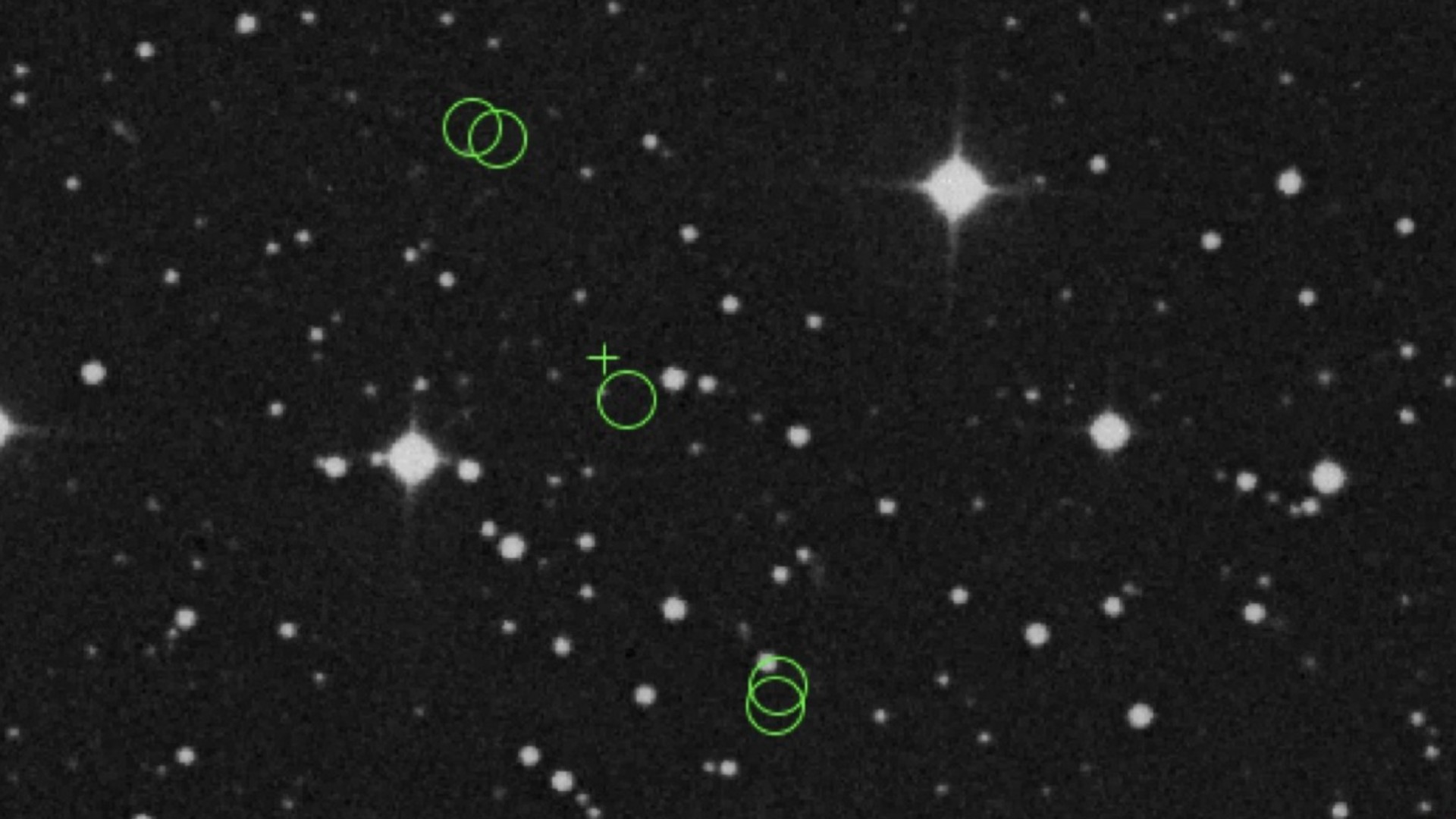

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time

01Two Black Holes Observed Circling Each Other for the First Time -

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life

02From Polymerization-Enabled Folding and Assembly to Chemical Evolution: Key Processes for Emergence of Functional Polymers in the Origin of Life -

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series)

03Astronomy 101: From the Sun and Moon to Wormholes and Warp Drive, Key Theories, Discoveries, and Facts about the Universe (The Adams 101 Series) -

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer

04True Anomaly hires former York Space executive as chief operating officer -

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images

05Φsat-2 begins science phase for AI Earth images -

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters

06Hurricane forecasters are losing 3 key satellites ahead of peak storm season − a meteorologist explains why it matters -

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly

07Binary star systems are complex astronomical objects − a new AI approach could pin down their properties quickly